Sharp new images show a tail that shouldn't point that way

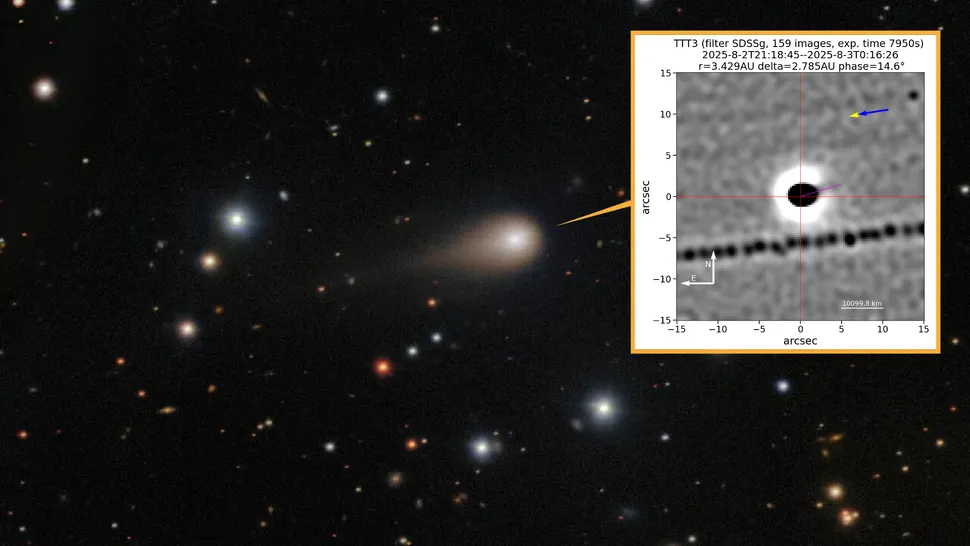

On 16 November 2025, observers from small automated telescopes to large facilities published fresh images of the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS that reveal a pronounced anti‑tail — a narrow dust structure that points toward the Sun — and, crucially, signs that its orientation has changed as the object closes on its nearest approach to Earth on 19 December 2025. Amateur astrophotographers such as Satoru Murata and teams operating Canary and Nordic telescopes captured the structure; space and ground observatories including Hubble, Gemini and ALMA have added higher‑resolution imaging and spectra in follow‑up observations.

The anti‑tail is rare but not unknown in cometary physics: under some geometric and particle‑size conditions the dust appears sunward from our viewpoint. What makes 3I/ATLAS notable is a cluster of properties that together are unusual — a large, sharply defined anti‑tail, multi‑jet structures in the coma, an elevated CO2-to-H2O ratio in early spectroscopic reports, and hints of non‑gravitational acceleration — and the recent change in the anti‑tail's direction has revived both conventional and more speculative explanations.

New observations and what they show

The recent images show at least two distinct features: a thin, well‑colimated main tail extending away from the Sun and a narrower sunward anti‑tail or jets that can be traced for millions of kilometres in projection. Observers report that the anti‑tail's apparent orientation has shifted relative to earlier images taken weeks before, a behaviour some teams say is hard to reconcile with simple geometric projection alone. In parallel, spectroscopic campaigns have flagged an unusually high CO2 relative to H2O in the coma and compositional oddities such as elevated nickel signals in some reductions — data points that are still being assessed and calibrated by multiple groups.

Because the object is on a hyperbolic trajectory and will pass closest to Earth at a safe distance of a few hundred million kilometres, no rendezvous is planned; instead, the scientific community is mounting an intense remote observing campaign. Telescope resources are being directed to track the changing dust morphology, measure outflow speeds, and monitor any non‑gravitational accelerations in the orbit through precise astrometry supplied to trajectory services such as JPL Horizons.

Natural models: dust, ice fragments and geometry

Finally, simple perspective effects still play a role. The apparent direction of dust features depends on the observer's line of sight relative to the comet's orbital plane; as position angles and viewing geometry change over weeks, tails and anti‑tails can appear to move without any exotic physics. Distinguishing these geometric effects from physical changes in the dust requires multi‑epoch, multi‑wavelength imaging and careful dynamical modelling.

Spectra, speeds and the artificial hypothesis

Alongside natural explanations, a minority of researchers have raised more speculative ideas because a set of anomalies persists: the anti‑tail's persistence despite changing geometry, narrow jet‑like features that do not smear with expected nucleus rotation, and reported non‑gravitational accelerations. Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb and collaborators have publicly framed some of the behaviours as testable hypotheses that could, in principle, be distinguished from natural outgassing.

It is important to stress that there is no direct evidence of intelligent or technological origin. The speculative hypothesis exists as a hypothesis to be tested — and testing requires the same data the community is already racing to collect: spectra that calibrate outflow speeds, long‑baseline astrometry to quantify non‑gravitational forces, and particle‑sensitive measurements in optical and radio bands.

Why astronomers are racing to observe

3I/ATLAS will not return. Its hyperbolic orbit means the object is a one‑time visitor from another stellar system, and the current weeks before and after closest approach are the only opportunity to collect high‑quality remote data. Observatories with cutting‑edge spectrographs and interferometers — Hubble, James Webb, ALMA, Gemini and major 2–4 metre class telescopes — are being used to capture the evolution of the coma and tails at multiple wavelengths. Amateur and semi‑professional telescopes are contributing high‑cadence imaging that can reveal fast morphological changes.

Practically, the community wants to pin down: (1) the particle‑size distribution and whether large, radiation‑resistant grains dominate the sunward structure; (2) gas composition and the CO2/H2O ratio, which affects grain lifetimes; (3) the velocity field of outflows from high‑resolution spectroscopy; and (4) any measurable non‑gravitational acceleration in the orbital solution maintained by JPL and other trajectory groups. Those four measurements together will let modellers decide which natural scenarios can be rejected and whether anything unexplained remains.

A clear outcome is the scientific win

For now, the majority of cometary scientists favour natural explanations while acknowledging the object is unusual. The response across the community — from small telescopes to flagship observatories — is exactly how science should work: collect data, test models, and be prepared to revise understanding when the evidence requires it. The coming weeks of coordinated observations will be decisive in clarifying whether 3I/ATLAS is an outlier in cometary diversity or a visitor that forces a deeper rethink.

What to watch for next

- High‑resolution spectra that measure outflow speeds and gas composition (especially CO2 and H2O lines).

- Multi‑epoch imaging from different latitudes and longitudes to separate geometry from physical change.

- Refined astrometry and orbit solutions that reveal or rule out sustained non‑gravitational acceleration.

- Polarimetric and infrared photometry to constrain grain sizes and thermal properties.

Until the data are in, the debate about 3I/ATLAS's moving anti‑tail will continue in observatory mailing lists, arXiv preprints and the pages of journals. The important point is that the question is resolvable: with rapid, careful observations the community can test competing models and move from speculation to measured conclusion.

Sources

- Harvard University (Avi Loeb, Galileo Project; Medium posts and arXiv preprints)

- NASA / JPL (astrometry, orbit solutions and Horizons trajectory updates)

- Major Planet Centre (object designation and observational reports)

- Hubble Space Telescope (imaging and space‑based follow‑up)

- Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) — spectroscopic observations

- Gemini Observatory, Nordic Optical Telescope, Canary telescopes (ground‑based imaging)

- arXiv (preprints and modelling papers on 3I/ATLAS dust and outgassing dynamics)