3I/ATLAS's Pulsing Jets: A Celestial Heartbeat

Why an interstellar object's 'heartbeat' matters

When the interstellar object known as 3I/ATLAS was first tracked in 2025, its behaviour looked odd but not inexplicable: a variable lightcurve with a clear, repeatable period. More than a year of follow‑up observations have now revealed that the periodic signal—a 16.16‑hour oscillation in brightness with an amplitude of order a few tenths of a magnitude—is not coming from a tumbling solid body the way many small Solar System objects vary. Instead, the dominant light appears to arise from a glowing coma fed by narrow, collimated jets that brighten and fade like a cosmic metronome.

This distinction is consequential. If the variability were simply the changing cross‑section of an elongated nucleus, we would be watching familiar rotational photometry. If the coma itself pulses, the physical mechanisms are different and the possible interpretations broaden—from mundane localized sublimation to more exotic hypotheses that some researchers urge should be tested rather than dismissed out of hand.

How we know the coma dominates the light

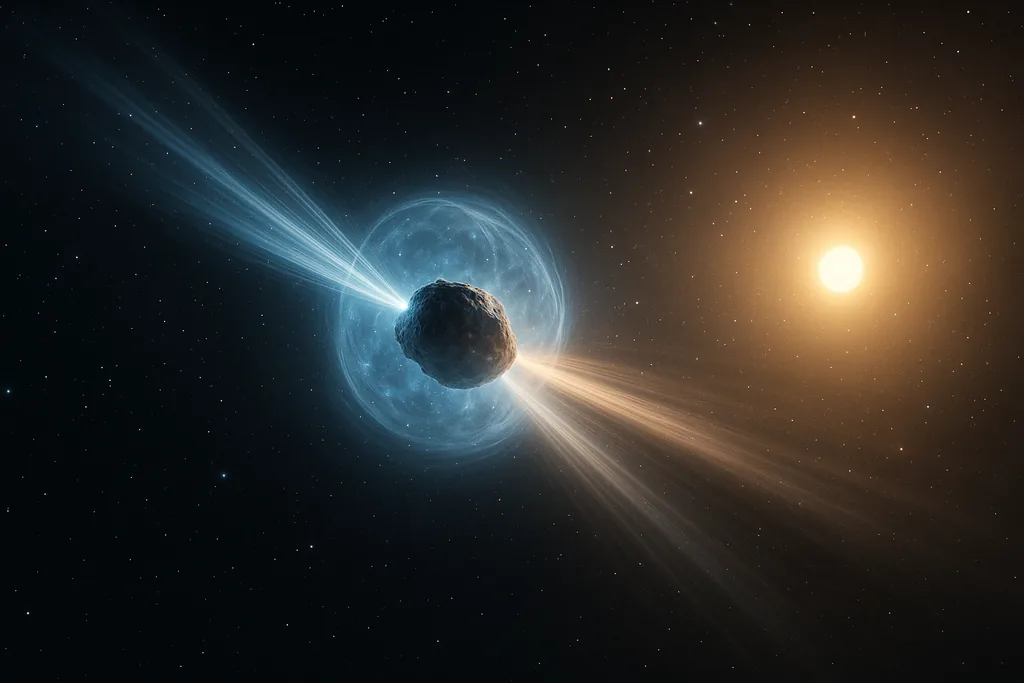

High‑resolution imaging—most notably from space telescopes—has shown that most of the optical flux from 3I/ATLAS comes from an extended, transparent halo of gas and dust rather than from a resolved, bright solid core. That halo, the coma, scatters sunlight and in the images appears to dominate the brightness profile. Where observers once estimated very large effective radii by naively attributing all the light to a bare surface, the coma‑dominated view forces a different calculation.

Jets that pulse, not just stream

Instead, recent analyses and images indicate multiple narrow jets streaming away from the nucleus into the coma. If the mass loss in those jets is pulsed—turning on and off or brightening periodically as different active patches on the nucleus rotate into sunlight—the coma brightness will rise and fall on the same rotation timescale. With an inferred outflow velocity on the order of 440 metres per second, material emitted during a single 16.16‑hour cycle can travel on the order of 25,000 kilometres. That is large compared with the nucleus itself, and it means the observable brightness modulation can be set by processes in the coma far from the solid core.

The physical picture for a natural comet is straightforward: a localized pocket of volatile ices heats when it faces the Sun, sublimates in a burst, and produces a collimated jet. As that pocket rotates away, the jet diminishes, and the coma appears to deflate until the next rotation—hence the heartbeat analogy. Observations showing persistently collimated structures and a repeatable period support this mechanism.

Where debate turns to wider implications

Not everyone is satisfied with a purely natural explanation. Avi Loeb, a prominent Harvard scientist who has previously argued that some interstellar interlopers deserve careful consideration as possible technological objects, has argued that the 16.16‑hour pulsed signal warrants exploration as a technosignature. In that view, periodic outbursts could, hypothetically, be tied to engineered operations—regular thrusting, attitude control, or power‑cycle phenomena—rather than to solar heating of exposed ice.

That claim has generated attention precisely because a clear, stable periodicity is one kind of pattern astronomers flag when searching for artificial signals. But extraordinary proposals raise the bar of evidence. The critical question is observational: are the jets aligned with the Sun, as expected for sublimation‑driven activity, or do they point in directions that require some other explanation?

How to test the competing ideas

There are concrete, near‑term tests that can decide between natural and less‑conventional interpretations.

- High‑cadence imaging "movies": sequences of well‑calibrated snapshots over multiple rotation cycles will show whether the pulsed brightenings follow the Sun‑facing geometry expected from thermal sublimation. If the brightening consistently points sunward, that points strongly to natural activity.

- Planetary encounter monitoring: the object's planned close approach to Jupiter offers a dynamical laboratory. If 3I/ATLAS undergoes a measurable, non‑gravitational manoeuvre while inside Jupiter's Hill sphere—one that cannot be modelled by outgassing torques—this would be a striking, direct indicator of control.

What the broader community says

Government and mission scientists maintain a cautious stance. Space agency teams emphasise that the observed coma and spectral properties are consistent with known cometary behaviour and that pulsed jets can naturally arise from heterogeneous surface composition and localized active vents. They also stress that further data—carefully calibrated, time‑resolved imaging and spectral monitoring—are essential to close the case.

Advocates for deeper scrutiny, including calls for wider release of raw data, argue that openness speeds discovery and strengthens public trust. The scientific method benefits from competing hypotheses and from tests designed to rule hypotheses in or out. That is precisely what the current debate over 3I/ATLAS demands.

Why the story matters beyond curiosity

3I/ATLAS is an interstellar messenger: it arrived from beyond the Sun's neighbourhood and carries information about processes in other systems. Understanding whether its pulsed jets are a quirk of cometary physics, a novel form of cryovolcanism, or an engineered behaviour has consequences for planetary science, small‑body physics, and the search for technosignatures. Even if the most conservative explanation holds, resolving the phenomenon will teach us about volatile transport, jet collimation, and how small bodies respond to intense heating during Solar System passages.

What to watch next

The path forward is observational. High‑resolution time‑series imaging, coordinated spectroscopy across wavelengths, and careful dynamical tracking during key approach phases will decide how the heartbeat story ends. Amateur observers can also contribute useful photometry, but the decisive measurements will likely come from space telescopes and large ground facilities able to resolve jet geometry and measure kinematics.

In science, patterns prompt questions; decisive experiments answer them. For now, 3I/ATLAS is pulsing, and astronomers are mobilising to record the rhythms in enough detail that nature—or something more—can be firmly identified.

— Mattias Risberg, Cologne