A landmark fusion milestone — why repeated 'ignition' matters, and why limitless energy is not here yet

What scientists announced — and why headlines called it "historic"

In December 2022 researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) reported a momentous laboratory result: an inertial‑confinement fusion experiment produced more fusion energy than the laser energy delivered to the tiny fuel capsule, a condition long called "ignition." The experiment released roughly 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy from about 2.05 megajoules of laser light aimed at a deuterium–tritium capsule — a clear demonstration that controlled fusion can, briefly, produce net energy at the target level. That announcement was followed by additional experiments that have repeatedly reached or exceeded that threshold, turning a one‑off success into a reproducible scientific regime. (llnl.gov)

How the NIF experiment works in plain language

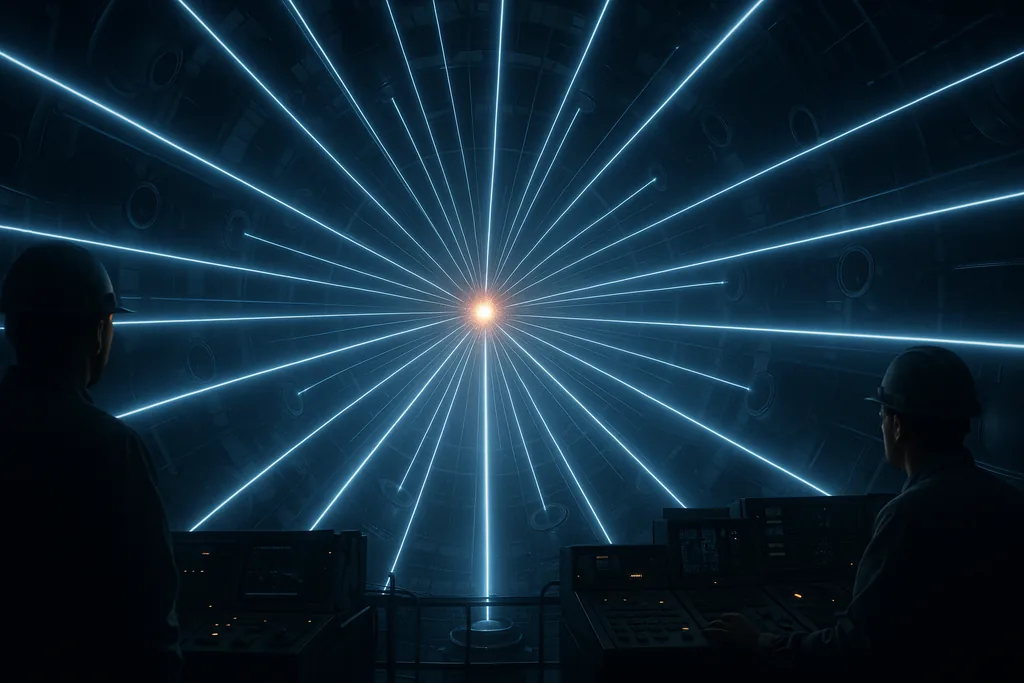

At the National Ignition Facility (NIF) an array of 192 high‑powered laser beams blasts a millimetre‑scale fuel capsule inside a gold 'hohlraum.' The laser pulse heats the hohlraum, generating X‑rays that implode the capsule and compress the deuterium–tritium fuel until temperatures and pressures are high enough for fusion reactions to occur. The fusion reaction produces alpha particles and neutrons; the heating effect of alpha particles can then amplify the burn for a brief instant — that transient self‑heating is what researchers call a "burning plasma" and, in favorable conditions, it leads to ignition. (llnl.gov)

Important progress — NIF has kept improving yields

LLNL has not only demonstrated ignition once. Over the subsequent months and years the team reported multiple shots that reached ignition and steadily higher yields: experiments in 2023 and 2024 produced larger fusion outputs, and LLNL has publicly described record shots through 2025 that pushed target yields into the multiple megajoule range, with one experiment in 2025 reporting an 8.6 MJ yield on a roughly 2.08 MJ laser pulse. Those repeatable results matter because they shift the conversation from "can ignition happen?" to "what conditions and designs produce high, reproducible gain?" — a necessary step toward any energy‑production concept built on the same physics. (lasers.llnl.gov)

Why this discovery is a scientific landmark — and what it is not

It is important to separate two different meanings of "net energy." The NIF experiments achieved net energy with respect to the energy incident on the fuel capsule — the energy that actually intercepts and compresses the tiny pellet. That is a fundamental scientific milestone: it proves that, under the right conditions, laboratory fusion can release more energy from the fuel than the local driver supplies. But engineering a power plant requires a very different metric: the plant must produce more electricity to the grid than the entire facility consumes to run lasers, pumps, cooling, target fabrication and more. NIF’s laser architecture uses large flashlamp‑pumped amplifiers with very low overall 'wall‑plug' efficiency, so the electrical energy needed to run a single megajoule‑class shot is orders of magnitude larger than the energy delivered to the capsule. Bridging that gap is an engineering challenge of a completely different scale. (cambridge.org)

The engineering hurdles that remain

- Driver efficiency and repetition rate. A power plant needs a driver (laser, particle beam, magnetic system) that converts grid electricity into fusion‑driving energy efficiently and can fire many times per second. NIF’s lasers were not designed for high repetition rates; current ICF power‑plant scenarios rely on diode‑pumped lasers and other technologies that could raise wall‑plug efficiency by orders of magnitude, but those systems still face scaling, cost and reliability challenges. (cambridge.org)

- Target manufacturing and economics. The tiny frozen fuel capsules NIF uses are delicate and costly. A commercial inertial‑fusion plant would require mass‑produced capsules at cents per piece and automated injection and tracking systems — a leap from today's laboratory targets. (platodata.ai)

- Fuel supply and tritium breeding. Most near‑term fusion concepts rely on deuterium–tritium fuel, but tritium is scarce in nature and must be bred inside the reactor using lithium blankets. Designing, testing and operating a reliable tritium breeding and handling system remains one of the central engineering questions for any D–T reactor. (nap.nationalacademies.org)

- Materials and neutron damage. D–T fusion releases energetic 14 MeV neutrons that will damage reactor walls and internal components. Materials that withstand sustained, high‑flux neutron bombardment over decades are still an active area of research; repairs and component replacement are expected to be major cost and availability drivers. (nap.nationalacademies.org)

Paths forward: how researchers plan to turn lab wins into power plants

Researchers and companies are attacking these problems on multiple fronts. For inertial fusion, work is underway to replace inefficient flashlamp pumps with diode‑pumped solid‑state lasers that could lift wall‑plug efficiency from fractions of a percent to several or even tens of percent, and to design targets and driver geometries with much higher target gain so that the fusion yield far exceeds the driver input. Magnetic confinement efforts (tokamaks and stellarators) follow a different route: they aim to hold a hot plasma for much longer durations and extract heat steadily, which shifts the engineering challenges toward continuous materials performance and tritium breeding in a different configuration. Both approaches — and a range of hybrid or emerging concepts — will probably contribute to long‑term solutions rather than a single winner. (cambridge.org)

What this means for energy and climate

If fusion can be made practical, with reliable fuel cycles, durable materials and favorable economics, its advantages are compelling: very high energy density, no carbon emissions during operation, and a reduced legacy‑waste profile compared with fission. The recent NIF work turns an old scientific question into something closer to an engineering program because it proves the physics in a laboratory setting. But engineers still need to design systems that convert that physics into kilowatt‑hours at a cost and reliability acceptable to utilities and regulators — a process likely to take years or decades, not months. (llnl.gov)

Bottom line

LLNL’s repeated ignition experiments are a genuine milestone: they demonstrate that controlled fusion can produce net energy at the target level and that the physics is now on firmer ground. That changes the question from "is fusion possible?" to "how fast can we solve the engineering problems that make it practical?" The answer will depend on progress in high‑efficiency drivers, mass‑production of targets (for inertial approaches), robust tritium breeding and new radiation‑tolerant materials. Progress is accelerating, but converting laboratory flashes of star‑like energy into steady, affordable electricity remains a major and worthwhile engineering challenge — one the world’s national labs, universities and companies are racing to solve.

— Mattias Risberg, Dark Matter, Cologne