A Possible First Direct Signal of Dark Matter

After a century of indirect clues, could dark matter have finally been seen?

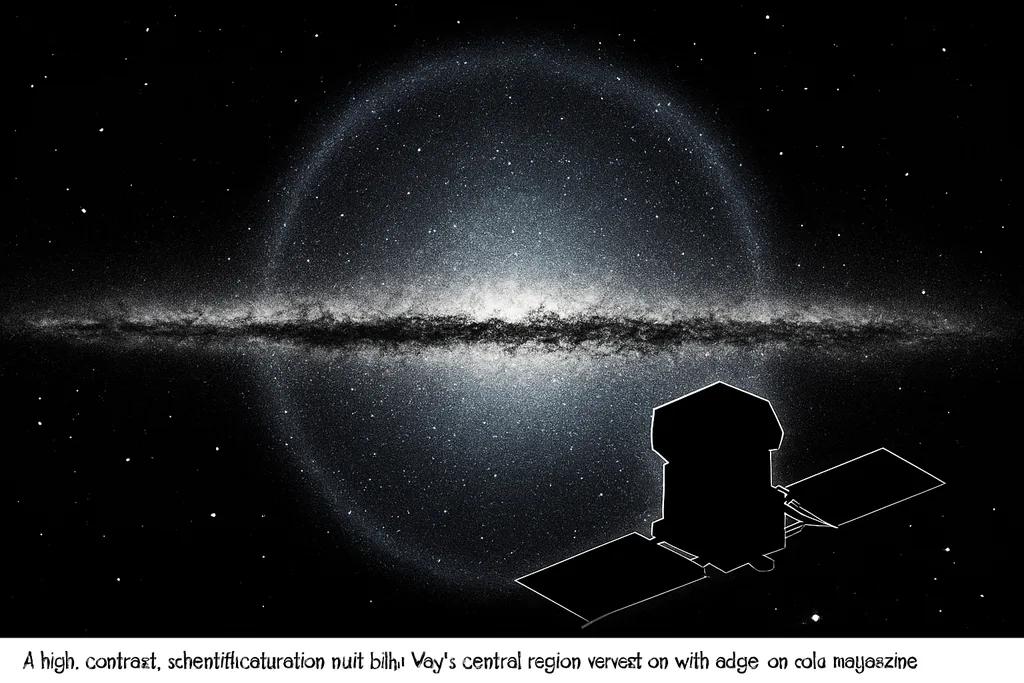

For nearly a hundred years astronomers have inferred the existence of dark matter from its gravitational fingerprints: galaxy rotation curves, gravitational lensing and large‑scale structure. This week a new analysis of data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma‑ray Space Telescope has reignited the debate by reporting a halo‑shaped excess of high‑energy gamma rays around the Galactic center that the author argues is consistent with the annihilation of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), a leading dark‑matter candidate.

What Totani did — and why it stands out

The team reprocessed 15 years of Fermi‑LAT data over a wide region of the sky off the Galactic plane, building maps and fitting them with a combination of known components: catalogued point sources, models for cosmic‑ray interactions (GALPROP), large extended features such as the Fermi bubbles and Loop I, and an isotropic background. After removing those contributions, they found a residual component with a spherically symmetric radial profile and a pronounced spectral peak around 20 GeV. The residual is small compared with the bright Galactic plane emission but persistent across a range of modeling choices, the author reports.

Numbers that matter

The best‑fit interpretation in terms of dark‑matter annihilation prefers particle masses on the order of 0.5–0.8 TeV and an annihilation cross section of order 5–8 × 10⁻²⁵ cm³ s⁻¹ for annihilation into bottom quarks. Totani and co‑authors emphasize that, while this cross section is greater than the canonical thermal relic benchmark (~3 × 10⁻²⁶ cm³ s⁻¹) and above many limits from observations of dwarf galaxies, uncertainties in the Milky Way’s inner density profile and systematic modeling choices mean the dark‑matter possibility cannot yet be ruled out.

Why most researchers will be cautious

Extraordinary claims demand extraordinary scrutiny. Gamma‑ray excesses toward the Galactic center have a long history — notably the so‑called GeV excess debated for more than a decade — and astrophysical explanations such as unresolved populations of pulsars or mismodelled cosmic‑ray interactions have repeatedly been proposed. Independent observers point out two immediate concerns: first, the annihilation cross section Totani finds is larger than the strong upper limits set by joint analyses of dwarf spheroidal galaxies, which are relatively clean, dark‑matter‑dominated targets; second, any dark‑matter interpretation ideally should reproduce a consistent signal in other dark‑matter‑rich environments. Those tensions keep the claim provisional.

Where the tension comes from

Dwarf spheroidal galaxies orbiting the Milky Way have long been the gold standard for gamma‑ray dark‑matter searches because they contain large mass‑to‑light ratios and few astrophysical gamma‑ray sources. Combined analyses from multiple gamma‑ray observatories have placed tight limits on annihilation cross sections across a broad mass range; a signal that requires a cross section an order of magnitude above those limits will naturally raise eyebrows. Totani’s paper addresses that tension by exploring uncertainties in the Milky Way’s density profile and by noting that systematic modelling differences can change the inferred cross section, but the tension is real and will be central to verification efforts.

What would strengthen or falsify the interpretation?

- Independent reanalysis of Fermi data: teams using different background models, event selections or analysis pipelines must recover the same halo‑like residual to build confidence.

- Detection in other targets: seeing a matching spectral signature from dwarf galaxies, galaxy clusters or dark subhalos would be a powerful corroboration.

- Cross‑instrument confirmation: ground‑based Cherenkov telescopes and the next‑generation Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA) have complementary energy coverage and angular resolution; they could confirm or rule out the spectral feature. Likewise, future Fermi work and multiwavelength studies will matter.

- Particle‑physics consistency: the implied particle mass and annihilation rate should fit within laboratory and cosmological constraints or motivate a credible new particle model that explains the required rate without conflicting with other data.

Why this would be transformative — if confirmed

A convincing detection of dark matter annihilation would do more than complete a missing page in cosmology: it would identify a new fundamental particle beyond the standard model, open a bridge between astrophysics and particle physics, and point experiments at colliders and direct‑detection facilities toward concrete target masses and interaction strengths. That is why the community will demand high standards of proof. The stakes are enormous, but so are the hurdles.

Bottom line

The Totani analysis presents an intriguing, carefully framed case for a halo‑shaped 20 GeV gamma‑ray excess that is compatible with WIMP annihilation, but it does not yet settle the question. The result is a strong candidate signal that will trigger further reanalyses, targeted searches in dwarf galaxies, and observations from other gamma‑ray facilities. Over the coming months — and especially as independent teams check the data and upcoming instruments probe the same energy regime — we’ll find out whether this is the long‑sought first glimpse of dark matter or another of the Universe’s stubborn astrophysical puzzles.

James Lawson is a science and technology reporter for Dark Matter. He holds an MSc in Science Communication and a BSc in Physics from University College London.