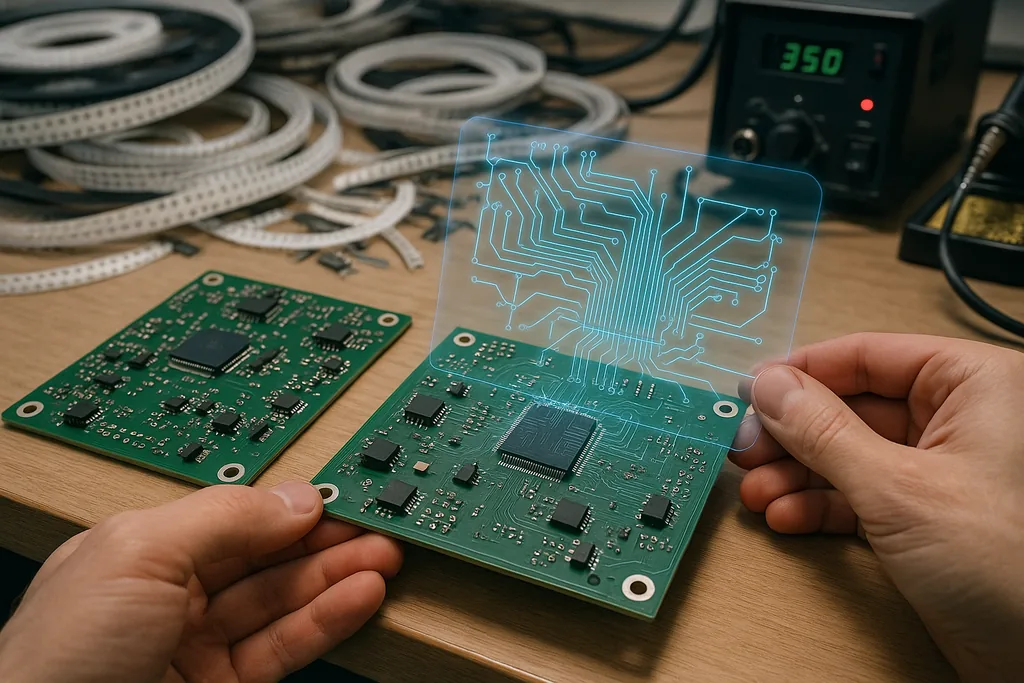

An AI took a schematic to a working Linux single‑board computer

On December 10, 2025 Quilter AI published a detailed account of Project Speedrun: an NXP 8M Mini–based Linux computer split across two printed circuit boards, containing 843 discrete components and 5,141 pins, that the company says its physics‑driven AI laid out and validated before the design was fabricated. Quilter posted the raw AI output, the cleaned production files, and a blow‑by‑blow of validation steps that culminated in a first‑power boot of Debian on the assembled hardware. The company also made the design files available for engineers to download and inspect.

How Quilter’s system differs from autorouters and LLM co‑pilots

Quilter positions its engine as a physics‑first generative system: rather than mimic human layouts or function like a large language model that predicts likely placements, the platform uses reinforcement learning and embedded physics checks to explore many candidate placements and routes in parallel. The goal, Quilter says, is to bake signal‑integrity, impedance targets, DDR length matching and manufacturing constraints into generation rather than fixing them after the fact in a conventional CAD workflow. That approach is intended to let teams rapidly produce multiple fabrication‑ready candidates and then select or polish the best option in native CAD tools.

From weeks of manual work to one week and a first‑boot

Quilter reports that Project Speedrun went from schematic to a running Linux system in under a week, with humans spending roughly 38.5 hours on setup and cleanup while the remainder of layout and routing was generated by the AI. Quilter contrasted that with a quoted 428 hours for a conventional manual layout of similar complexity. After fabrication and assembly, the dual‑PCB board powered up and booted Debian on the first attempt, then ran ordinary workloads such as video playback, a simple game demo and productivity applications during validation. Those claims have been widely reported in trade coverage and are documented in Quilter’s project materials.

What the first‑boot win actually proves

Booting on the first try is a useful and tangible milestone in hardware development because it demonstrates that supply routing, power rails and basic device initialization are present and correct. But boot success alone is not a full endorsement of long‑term reliability, thermal behaviour under sustained load, or corner‑case signal problems that typically surface during extended soak testing or in high‑speed interfaces. Trade coverage has noted both the significance of a first‑boot and the limits of that milestone: it proves the concept and reduces early‑cycle risk, but it does not replace full validation and in‑field qualification. Quilter’s own documentation shows follow‑up stress testing and notes where engineers applied a human cleanup pass before sending files to the fabricator.

Technical choices and constraints: the 8M Mini platform

The Project Speedrun system uses an NXP 8M Mini application processor as its compute heart — a widely used embedded ARM SoC family with up to four Cortex‑A53 cores, multimedia acceleration and a range of peripheral interfaces. That choice shapes layout rules for power islands, DDR routing and high‑speed interfaces such as PCIe and Gigabit Ethernet, and it gives the validation team a well‑documented set of constraints to feed into the AI. Using a known, well‑characterised SoC helps make automated verification tractable because the physics checks and timing budgets have clear targets to meet.

What changed in the workflow — and why it matters

Traditional PCB workflows place a heavy emphasis on human layout expertise: part clustering, decoupling geometry, return paths, differential pair routing and manufacturability trade‑offs are all skillful, time‑consuming manual tasks. Quilter’s pitch is that by automating the repetitive and rule‑driven parts of that work, system engineers can iterate far more designs in a given calendar window, discover layouts that human intuition would miss, and focus human time on higher‑value system questions — firmware, test plans and board‑level diagnostics. For teams shipping multiple board variants or building evaluation platforms, that compression of lead time could materially change product roadmaps and reduce the cost of experimentation.

Checks, trust and the need for third‑party validation

Implications for supply chains, small teams and the semiconductor landscape

If automated layout tools reliably compress layout time from months to days, smaller teams can iterate hardware faster and start product validation sooner — a shift with obvious implications for startups and companies that rely on rapid prototyping. It could also change where and how specialist layout work is sourced: routine layout might become a commodity task while expert layout engineers concentrate on the hardest signal‑integrity challenges and system optimisation. On the other hand, faster iteration increases the demand for quick turn fabrication and reliable parts supply, so logistics and procurement will remain critical bottlenecks even if layout stops being one.

Where verification, regulation and safety enter the conversation

Automating layout does not remove regulatory responsibilities. Products in medical, automotive or aerospace domains require formal design assurance, traceability and sometimes accredited verification processes. Any workflow that inserts automated generation must preserve provenance: who set constraints, which rules were enforced, and what checks were performed before fabrication. Quilter’s documentation and file releases are a step toward transparency, but regulated industries will demand process audits and reproducibility before adopting autonomous layout engines for safety‑critical boards.

What to watch next

Project Speedrun is an early public demonstration rather than an industry‑scale deployment, but it makes clear where the innovation is heading: physics‑aware generative systems coupled to conventional CAD toolchains. The near‑term milestones to watch for are independent third‑party verifications of AI‑generated boards across a range of form factors; published case studies in regulated domains; and competitive responses from established CAD vendors. How quickly organizations incorporate autonomous layout will depend on the repeatability of results, the cost and capacity of fabrication partners, and the degree to which teams adopt new verification practices.

Project Speedrun does not rewrite hardware engineering overnight, but it does compress a high‑friction stage of the workflow into something that looks far more like software iteration: faster candidates, more tests, and earlier learning loops. That is a meaningful development for anyone who ships boards — from hobbyists and university labs up to industrial design teams and hardware startups. The practical value will become clearer as more organisations run Quilter’s files through their own validation pipelines and publish the results.

Sources

- Quilter AI — Project Speedrun design files and technical documentation (Project page and downloads)

- Quilter AI — Technical blog series on physics‑driven layout and platform comparisons

- NXP — 8M Mini product page and datasheet