Stormy night, a clipped lock and a two-century experiment

On a storm-lashed day soon after Ludwig van Beethoven’s death in March 1827, mourners clipped a lock of the composer’s hair—a relic that has passed through collectors, museums and skepticism ever since. Nearly two hundred years later an international team led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology sequenced DNA from authenticated strands and published a comprehensive analysis in 2023. Their results change parts of the story we tell about Beethoven: they point to a viral infection and inherited liver risk as likely contributors to his decline, debunk a much-cited lead-poisoning narrative tied to misidentified material, and reveal a surprising break in the composer’s paternal line.

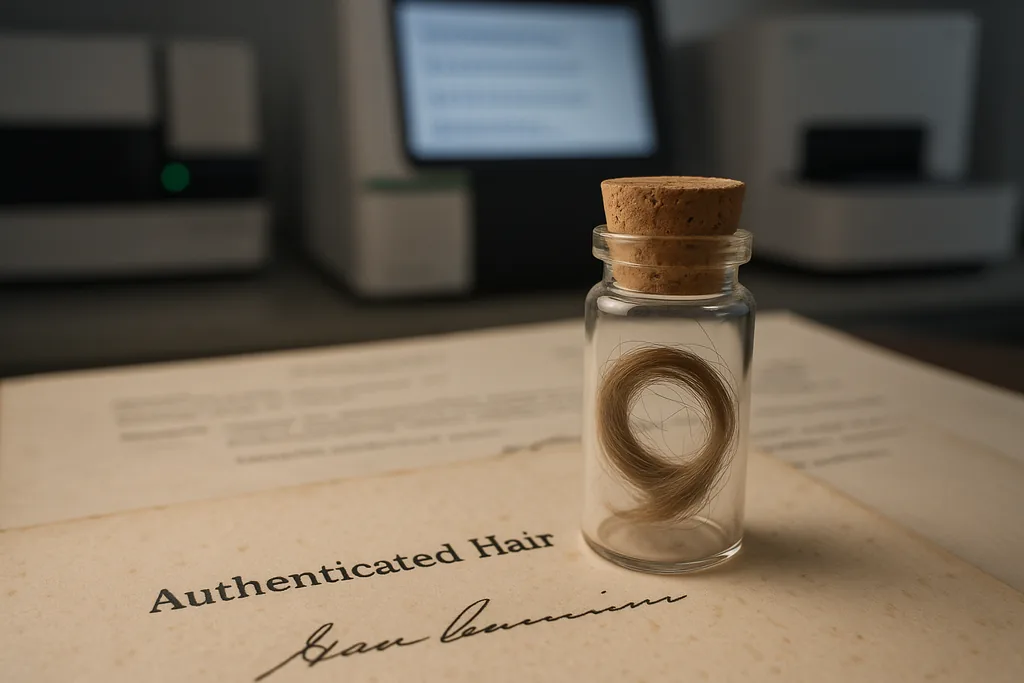

How hair became a time capsule

The study used methods borrowed from palaeogenomics: careful authentication of historic material, contamination controls, and deep sequencing of minute amounts of hair DNA. The team identified five locks whose provenance could be established with historical documentation and molecular consistency; those samples produced a high-coverage genome for analysis. That technical achievement made it possible to search Beethoven’s genome for disease-associated variants, detect viral DNA fragments, and compare his Y chromosome to those of living patrilineal relatives.

Sequencing hair—keratinized tissue with degraded DNA—requires specialized extraction and library-preparation protocols. The researchers combined those laboratory techniques with genealogical testing, matching genetic signatures to regional reference panels to confirm Beethoven’s continental ancestry and to validate the biological links between the hairs themselves.

Genetic clues to liver disease and a viral infection

The genetic portrait that emerged is not a neat, single-cause explanation for Beethoven’s death, but it is materially different from long-standing stories. The team detected genomic markers that point to an increased inherited risk of liver disease. More directly, analysis of the authenticated strands uncovered evidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in tissue dating to Beethoven’s final months. When combined with contemporaneous accounts of jaundice, abdominal swelling and progressive liver dysfunction, the presence of HBV provides a plausible—and testable—mechanism that could have accelerated hepatic failure.

Crucially, the new genetic evidence undercuts a theory that has had wide circulation: that lead poisoning was the primary cause of Beethoven’s symptoms. Earlier reports of high lead levels were based on analyses of a sample subsequently shown not to belong to the composer. The 2023 study’s authenticated hair samples do not support lead as the main driver of his terminal illness, though they do not rule out some historical lead exposures entirely. The weight of the evidence now favors a picture in which chronic alcohol consumption, inherited susceptibility, and an HBV infection conspired to damage Beethoven’s liver.

The missing Y: a family twist

Perhaps the most unexpectedly human finding concerns Beethoven’s paternal lineage. The team compared the Y chromosome recovered from authenticated hair with the Y-chromosomal profiles of living men who trace their descent through the documented Beethoven patriline. The profiles did not match. Because the Y chromosome is transmitted father to son, a mismatch indicates a non-paternal event somewhere between the documented ancestor Hendrik van Beethoven—born around 1572—and Ludwig’s own birth in 1770. The simplest interpretation is that one branch of the recorded genealogy does not reflect the biological father of a child at some point in those generations.

That discovery does not scandalize the facts of Beethoven’s music, but it changes how historians and genealogists reconstruct his family story. It is also a reminder that genetic and documentary lines of evidence can diverge, and that personal histories—even of famous figures—contain ordinary human complications.

Unresolved mysteries: deafness and chronic pain

Despite the new genomic resources, the analysis failed to deliver definitive answers for two of the composer’s most enduring medical enigmas. Researchers did not identify clear pathogenic mutations that would account for Beethoven’s progressive high-frequency hearing loss, which began in his twenties and left him essentially deaf by his late forties. Similarly, the chronic gastrointestinal pain and bouts of diarrhea recorded through much of his adult life remain unexplained by the genetic data available.

These negative results are important: they show the limits of genetics, particularly when an illness can arise from a complex interplay of environmental exposures, infections, medication practices of the time, and—possibly—non-genetic factors such as trauma or autoimmune processes. The absence of a smoking-gun mutation does not rule out genetic contributors, but it highlights the need for integrated historical, clinical and molecular analysis.

Authentication, provenance and the ethics of historical DNA

One of the study’s practical lessons is methodological: the provenance of historical specimens matters immensely. The team showed that a widely cited hair sample attributed to Beethoven and used in earlier lead analyses was in fact not his; that misattribution reshaped decades of debate. The Max Planck-led study demonstrates how cross-disciplinary verification—archival research, chain-of-custody documentation and molecular relatedness testing—must precede forensic or medical claims based on ancient or historic DNA.

Beyond laboratory rigor, the work raises ethical questions. Sequencing the genome of a cultural icon touches living relatives and communities; it opens interpretive space for speculation about cause of death, paternity and private health. The researchers handled those sensitivities by focusing on aggregate medical insights and by collaborating with museums and custodians. But as genomic sleuthing of historical figures becomes more routine, institutions will need clearer policies for consent, disclosure and respect for descendant communities.

Why these findings matter

At first glance this is a story about a famous composer and an arcane laboratory technique. In practice it is an example of how modern genomics can revise historical narratives. The study moves us from speculation to evidence-based, probabilistic conclusions about illness, ancestry and family structure. It also reframes Beethoven as a person coping with multiple, interacting health problems rather than a single defining pathology.

For historians, the work supplies new datapoints: when to trust archival claims, how to weigh contradictory artifacts, and how to place medical testimony from the early 19th century beside modern molecular evidence. For clinicians and geneticists it demonstrates the potential—and the limits—of genomic analysis on preserved human tissue. And for the public, it is a reminder that science can complicate, not simply confirm, our stories about the past.

Two centuries after his death, Beethoven’s clipped hair has done what few documents could: it has brought fresh material evidence into debates that had relied on inference and lore. The strands have not answered every question, but they have redirected inquiry toward infection, inherited risk and family history—details that enrich our understanding of the man who shaped modern music.

Sources

- Current Biology (research paper on Beethoven’s DNA)

- Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (press materials)

- University of Cambridge (research and press materials)