Hefei cranes and secret laser halls: a new front in the energy race

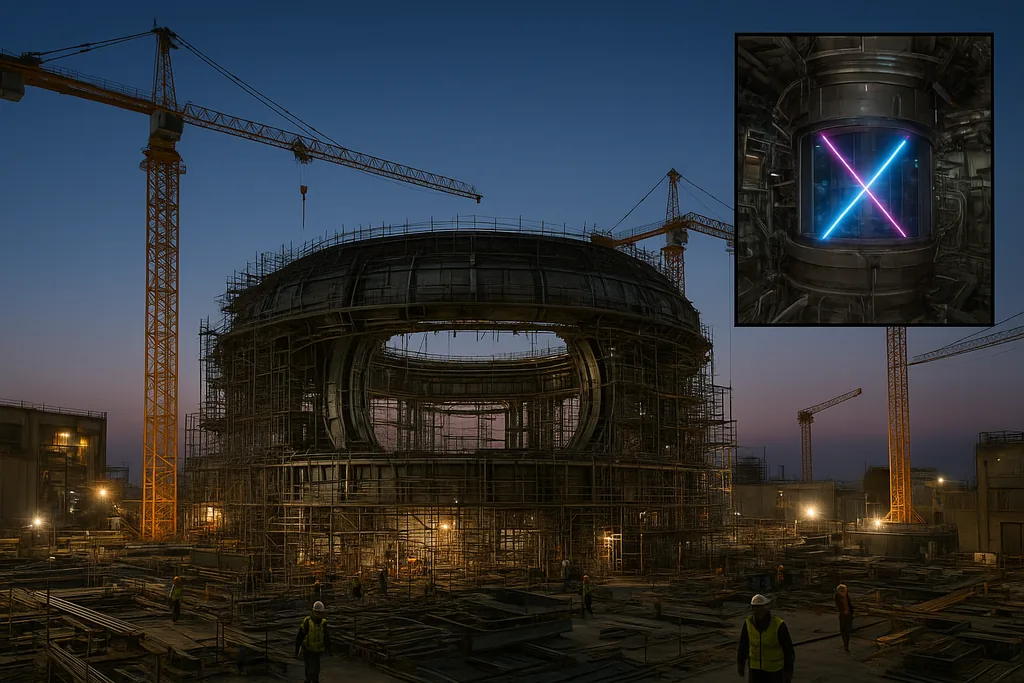

On a leafy research campus in eastern China this December 2025, construction crews work through pale winter light to close the rings of a vast doughnut-shaped machine while large cranes stand guard over concrete foundations. In the country’s southwest, analysts scrutinizing satellite images have identified an X-shaped hall whose scale and geometry point to a new, high‑power laser facility. These twin projects — a tokamak called BEST and a laser-ignition site tied to the Shenguang programme — are the most visible signs of an intensified Chinese campaign to make fusion power real.

Two technologies, one ambition

Fusion research splits into distinct technical paths. Tokamaks use magnetic fields to confine hot plasma in a torus, relying on giant magnets to hold hydrogen isotopes together long enough for fusion to occur. Inertial confinement fusion, pursued with high-energy lasers, packs energy into tiny fuel pellets until they implode and briefly reach fusion conditions. China is pursuing both in parallel — matching the United States and other nations in laboratory breakthroughs while accelerating construction and investment at a national scale.

In the United States, the strategy has tilted toward private innovation. A cluster of startups has attracted venture capital and public grants to turn lab successes into prototype reactors; Commonwealth Fusion Systems is among those targeting a device capable of producing more energy than required to run it by the late 2020s. In China, the rhythm is different: national research institutes and state-owned companies are channeling large sums and industrial capacity into facilities they control directly. This state-led approach is buying speed and scale, and it is reshaping the global timetable for fusion development.

What Beijing is building

China’s Institute of Plasma Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences is completing BEST, a tokamak designed to push several critical engineering elements at once. Nearby, a 100‑acre complex is being prepared for testing components that must survive the punishing environment inside a working reactor: extreme heat, intense neutron flux and the mechanical stresses of repeated operation. Officials from the institute have framed fusion as a strategic scientific priority in the next five-year plan, and construction is moving at a cadence that surprised many Western researchers.

Parallel to the tokamak programme, the China Academy of Engineering Physics — an organisation with historic links to weapons stewardship — has accelerated a laser path. Reports and patent filings point to Shenguang IV and related facilities in Mianyang and Chengdu. That work draws directly from the scientific lessons of the United States’ inertial confinement experiments but proceeds with an urgency and secrecy shaped by both defence considerations and the desire to master a potentially transformative energy technology.

Where private industry fits in

Private firms in the United States and elsewhere chase agility: new magnet designs, novel confinement concepts, and modular engineering to get to a pilot plant quickly. One high‑visibility innovation is a class of powerful, compact magnets made possible by newer superconducting materials; researchers in both Massachusetts and Shanghai have reported similar engineering milestones for these magnets in the past year. For the U.S. model to deliver, however, it must clear two barriers: sustained funding over long development cycles and an industrial base capable of building plants at scale.

Technical and industrial hurdles remain

Even if laboratories demonstrate net energy for short periods, getting from an experimental milestone to a reliable, economical power plant is a separate problem. Fusion systems must handle continuous or high‑duty operation: feeding fuel, extracting heat, breeding tritium, protecting structural materials from energetic neutrons, and doing all that with reasonable cost and maintainability. These are largely engineering problems — big, expensive, and often mundane — where construction expertise, supply chains and materials science matter as much as physics.

China’s established strengths in large-scale engineering and rapid construction give it advantages in those areas. That was evident when a Shanghai startup published a magnet design similar in capability to one produced by an American firm less than a year after the U.S. team published its results. Rapidly mobilising supply chains and manufacturing competence demonstrated an ability to translate lab concepts into hardware quickly; whether that hardware will operate reliably as part of a commercial power plant is unproven.

Science, secrecy and geopolitics

The fusion race is not just about electricity. Laser facilities in particular have dual-use value for nuclear-weapons stewardship, and that duality explains some of the secrecy around certain Chinese projects. The same laser systems that aim to create fusion ignition also allow countries to study extremely high‑energy density physics without nuclear explosions. That overlap complicates international collaboration when strategic competitors view advanced facilities through both civilian and military lenses.

Policy decisions in Washington have already changed the shape of academic exchange: some U.S. programmes and funding signals have discouraged participation in certain international fusion conferences or slowed joint experiments. That has pushed more scientists toward startups or into international positions — a migration China is trying to capture by recruiting researchers from U.S. labs and universities. Whether this results in a permanent decoupling of the field, or a competitive but still collaborative international ecology, depends on future policy choices and on how rapidly the technology approaches commercial thresholds.

What success would mean — and how soon

Researchers and company leaders offer optimistic timelines for milestones: short-term demonstrations of net energy in experimental devices are plausible in the next few years; pilot plants capable of feeding a grid might appear in the 2030s; full commercial rollouts could follow in the 2040s if everything goes well. Some entrepreneurs and planners in China are even aiming for commercial demonstration by 2040 in more ambitious forecasts.

The prize is enormous. Fusion fuel — isotopes of hydrogen like deuterium and tritium — is plentiful, and fusion produces energy without the runaway meltdown risks associated with fission and with far lower volumes of long-lived radioactive waste. If fusion can be made compact, reliable and affordable, it could supply baseload power for energy-intensive industries, data centres powering artificial intelligence, desalination, or hard-to-electrify sectors such as steelmaking and shipping. Whoever develops the capacity to build, operate and export fusion plants could gain not just commercial advantage but geopolitical influence.

A careful watch

In the near term, observers should expect more headline-grabbing prototypes and continued competition over talent and supply chains. The technical story will proceed in measured steps: milestones announced by labs and companies, independent peer-reviewed results, and the slow accumulation of engineering knowledge about how systems behave when run repeatedly. Grand promises will be tested against the unglamorous truth that electricity production at planetary scale is a systems problem as much as a physics problem.

China’s fusion surge raises the stakes and accelerates the schedule. Whether that speed will translate into practical, affordable power in time to reshape this century’s energy and industrial map remains to be seen — but the race is now unmistakably on.

Sources

- Institute of Plasma Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences

- China Academy of Engineering Physics

- ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor)

- Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- U.S. Department of Energy

- Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL)

- Peking University