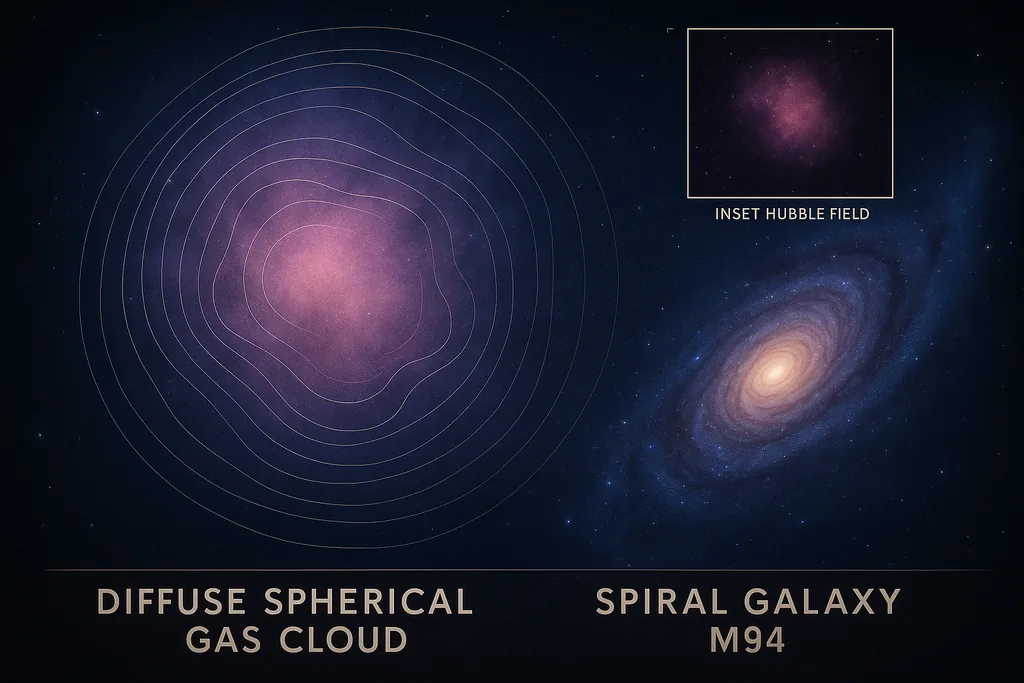

An empty, spherical ghost near M94

On January 5, 2026, researchers announced that the Hubble Space Telescope has confirmed a never-before-seen class of object: a compact, starless cloud of neutral hydrogen bound inside a halo of dark matter. Nicknamed "Cloud‑9," the structure sits on the outskirts of the nearby spiral galaxy Messier 94 (M94), roughly 14 million light‑years from Earth, and has become a poster child for a theoretical species called a RELHIC — a reionization‑limited H I cloud.

A relic, not a dwarf galaxy

Measured properties place the hydrogen core at about 4,900 light‑years across and containing roughly one million solar masses of neutral hydrogen, while dynamical inference implies a dark matter halo of order five billion solar masses — a mass budget more typical of small galaxies than of isolated gas clouds. The mismatch — a massive dark halo with almost no stars — is what makes Cloud‑9 a "failed galaxy" in the literal sense: it carries the gravitational skeleton of a galaxy but never lit up with stars.

How astronomers confirm 'starlessness'

Proving that a region of the sky contains no stars is harder than it sounds. Observers must exclude faint, old stellar populations and background galaxies that can masquerade as inhabitants of a nearby object. The research team combined sensitive radio maps from arrays such as the Very Large Array with targeted Hubble imaging to look for resolved stars at the distance of M94; the Hubble data were deep enough to find stars down to extremely low luminosities and found at most a handful of candidates that could be foreground or background contaminants rather than true members. Based on simulations and the absence of a statistically significant stellar sequence, the authors estimate an upper limit of only a few thousand solar masses in stars — far too few for Cloud‑9 to qualify as a dwarf galaxy.

Why theory predicted objects like Cloud‑9

Cosmological theory predicts that the universe should be filled with dark matter halos of many sizes; only some of those halos ever collect enough gas to cool, collapse, and form stars. During the epoch of reionization — when the first stars and galaxies ionized the intergalactic medium — the smallest halos were vulnerable: ultraviolet radiation and heating could prevent gas from cooling and condensing, leaving behind dark halos with little or no star formation. RELHICs are the fossil remains of that process: halos that retained enough neutral hydrogen to be detected in 21‑centimeter radio emission but never turned the gas into a stellar population. Cloud‑9 appears to match the predicted properties of such a relic.

What Cloud‑9 reveals about dark matter

How rare are RELHICs, and why we missed them

Cloud‑9 was first picked up in radio data years ago, but it took Hubble's resolving power to show that it is essentially empty of stars. Part of the reason similar clouds have been hard to find is observational bias: astronomical surveys naturally focus on bright, starlit galaxies because they are easier to detect and catalog. Compact, neutral‑hydrogen structures with little or no starlight slip through such searches unless targeted with radio telescopes and followed up at high spatial resolution. The discovery team argues that there may well be many more RELHICs lurking near other galaxies, waiting for the right combination of radio sensitivity and optical resolution to reveal them.

Implications for galaxy formation and future searches

Cloud‑9 gives theorists a direct data point for the low end of the galaxy‑formation ladder. If RELHICs are numerous, they represent a population of dark halos that contributed to the cosmic inventory of mass but not to the luminous census of galaxies. That changes how astronomers connect the visible distribution of galaxies to the underlying dark matter scaffolding — a key ingredient for precision cosmology. Moreover, finding more RELHICs will let researchers map how common these failed galaxies are as a function of environment: do they cluster around big spirals like M94, are they isolated, or are they preferentially found in certain cosmic neighborhoods?

Planned and ongoing radio surveys — including those with upgraded interferometers and next‑generation facilities — will improve sensitivity to low‑mass neutral hydrogen clouds. Coupled with space telescope follow‑ups to search for even the faintest stars, these campaigns could establish whether Cloud‑9 is a solitary curiosity or the tip of a hidden iceberg. Team members also flagged the importance of spectral studies to probe the ionization state and metallicity of Cloud‑9's gas, measurements that would help pin down its origin: whether it is a primordial fossil that never formed stars, or gas stripped from a nearby galaxy by tidal forces.

Careful optimism and the next steps

For now, Cloud‑9 stands as a vivid example of how much of the universe's mass can remain hidden behind darkness and silence. It is a reminder that the cosmic story includes not only brilliant galaxies but also the quiet failures that shaped the distribution of matter long before stars lit the sky; tracing those failures back to first principles may help answer one of modern astronomy's most persistent puzzles — what dark matter really is, and how it orchestrated the formation of structure in the cosmos.

Sources

- The Astrophysical Journal Letters (peer‑reviewed research paper on Cloud‑9)

- NASA Goddard Space Flight Center / Hubble Space Telescope mission materials

- European Space Agency (ESA) Science releases

- Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI)

- University of Milano‑Bicocca (research team lead and principal investigator)

- National Radio Astronomy Observatory / Very Large Array (VLA) data contributions