Enceladus: Cassini Finds New Life-Clues

Decade-old data, new implications

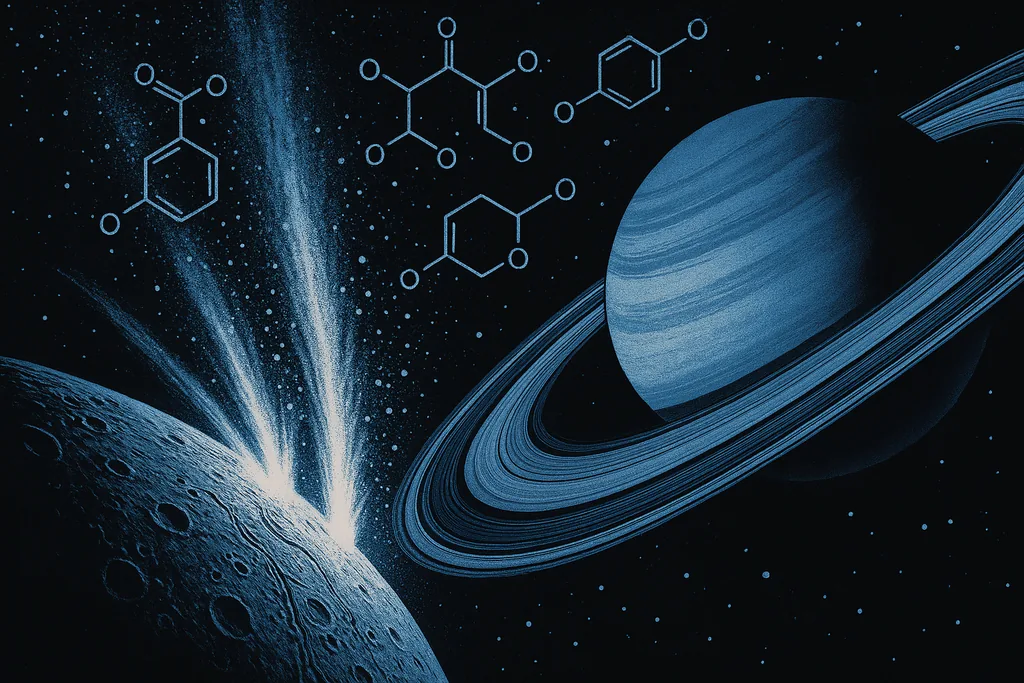

Scientists working with archived measurements from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft have identified chemical fingerprints in freshly ejected ice grains that point to active organic chemistry inside Saturn’s moon Enceladus. The analysis turned up molecular fragments — including esters, ethers, cyclic hydrocarbons and nitrogen–oxygen containing compounds — in material that originated directly from the moon’s subsurface ocean, not from the aged dust that drifts around Saturn. These intermediates are the kind of molecules that chemists recognise as potential stepping-stones toward amino acids and other biologically relevant compounds.

That finding comes from a new study that re-examined flyby data from Cassini’s encounters with the moon and its plumes. Because the grains the team analysed were sampled just after they were ejected, they carry a much less altered chemical record than particles that have orbited for years and been processed by radiation in space. The result is a clearer window on the ocean chemistry happening beneath Enceladus’s icy crust.

Why freshly ejected grains matter

When ice grains are launched from the venting region near Enceladus’s south pole, some fall back quickly and others get swept into Saturn’s E ring, where they can spend centuries exposed to charged particles and ultraviolet light. That space weathering can break down or alter delicate organic molecules, masking the original chemistry. By isolating grains that were collected very soon after eruption, researchers reduced that ambiguity and found molecular fragments that are consistent with active, ongoing synthesis in the sub-ice ocean itself rather than being products of space processing.

Threads from an energetic deep sea

Cassini’s legacy already included three strong clues that Enceladus’s ocean is not a stagnant puddle. The spacecraft detected microscopic silica particles whose size and chemistry are best explained by hot water–rock reactions at the seafloor — a hallmark of hydrothermal vents on Earth — and later measurements showed molecular hydrogen in the plume, a potent source of chemical energy for microbes. In short, the moon supplies liquid water, a free energy source and now increasingly complex organic chemistry — the basic checklist for habitability as we understand it.

How these molecules fit into life’s recipe

The newly identified fragments are not intact proteins or DNA; they are smaller chemical pieces that can participate in reaction chains leading to larger biomolecules. On Earth, chains of reactions that produce esters, ethers and certain cyclic structures can lead to amino-acid precursors and lipid components. Detecting these intermediates in fresh plume material suggests that Enceladus’s ocean hosts a dynamic organic chemistry that could — given time and the right conditions — assemble more complex species. But there is an important caveat: abiotic (non-biological) chemistry can also generate these same intermediates under hydrothermal conditions, so their presence is an indicator of chemical richness, not a biosignature by itself.

Phosphorus and other life ingredients

Previous Cassini-era research had already closed other major gaps in Enceladus’s habitability ledger. Analyses of salt-rich ice grains revealed the presence of phosphate — the form of phosphorus used in DNA, cell membranes and energy-carrier molecules on Earth — at concentrations estimated to be orders of magnitude higher than typical seawater. The detection of phosphorus, combined with the new inventory of organic intermediates and evidence for energy-yielding chemistry, paints a picture of an ocean that meets the three broad requirements for life: solvent, biochemistry and a usable energy source.

Limits of what Cassini can tell us

It’s vital to be clear about what these discoveries do and do not show. Cassini was not equipped to identify living organisms or to run the kinds of sequencing and isotopic tests that would provide convincing biosignatures. The spacecraft sampled plume gases and micron-sized ice particles; instruments measured mass fragments and element ratios rather than intact organisms. The new chemical detections increase the plausibility that life could exist there, but they fall short of proof. Distinguishing biological production from abiotic chemistry will require targeted, high-sensitivity instrumentation and mission designs optimised to test for life.

What comes next: missions and measurements

These results have strengthened the scientific case for returning to Enceladus with hardware designed specifically for astrobiology. Community roadmaps and strategy reports over recent years have flagged Enceladus as a top candidate for a flagship-class mission: concepts range from orbiters that repeatedly sample the plume to 'orbilander' architectures that combine plume sampling with short surface operations. Designing instruments that can catch fresh plume material, preserve fragile organics and discriminate between abiotic and biotic chemical pathways will be central to any future campaign.

Why this matters

Perhaps the most striking aspect of the story is how much new science can be wrung from existing data when fresh analysis techniques and new scientific questions are applied. Cassini’s datasets continue to reward careful re-examination, and the chemistry now coming into focus on Enceladus elevates the moon from a fascinating curiosity to a prime laboratory for testing ideas about how life starts and survives in icy ocean worlds. If future missions confirm that hydrothermal systems on Enceladus are producing complex organics at scale, we will have taken a decisive step toward answering one of humanity’s oldest questions: are we alone?

— James Lawson, MSc Science Communication, BSc Physics