EPA website edits shift emphasis away from human causes

On December 9, 2025, reporters found that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency had quietly altered and in some cases deleted a number of climate-related web pages — removing clear statements that human activity is the dominant driver of modern warming and instead highlighting “natural processes” such as volcanic activity and changes in solar energy. The edits affect pages used widely by educators and the public, including a high-traffic page titled “Causes of Climate Change,” which previously quoted the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s unequivocal wording about human influence. Critics say the change rewrites the basic science the agency has long presented to the public.

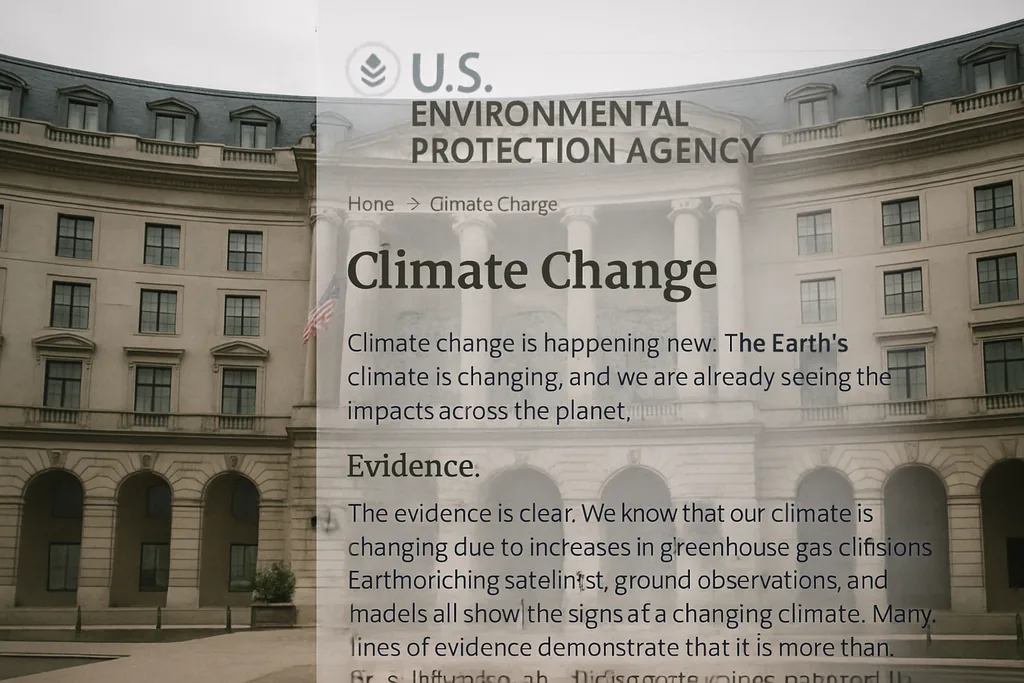

Website edits and deletions

On the page that once listed causes and contributors, language that directly credited the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities with nearly all of the observed 20th- and 21st-century warming was shortened or removed, leaving only a paragraph noting that “natural processes are always influencing the earth’s climate.” An archived version available through web caches and the Internet Archive shows the earlier text explicitly referenced carbon dioxide emissions since the Industrial Revolution; the current live page omits that passage and, in some places, replaces it with material about orbital and volcanic variability that pertains to pre-industrial climate changes. In other cases, pages that tracked observable indicators of climate change — shrinking Arctic sea ice, rising seas, and increased coastal flooding — were deleted, and FAQ pages were stripped of questions about consensus, health impacts and who is most at risk.

Users who clicked links from archived or resource pages sometimes encountered broken XML feeds or error messages rather than the datasets and explanatory text that had previously been available, leading educators and researchers to warn that the site no longer functions as the public-facing clearinghouse it had been. That break in navigability has practical effects: teachers, local officials and community groups who relied on EPA summaries and cleanly linked resources now face an additional burden to locate authoritative sources elsewhere.

Voices from science and policy

Scientists, former EPA officials and public-interest organizations reacted sharply. University of California climate scientist Daniel Swain said the edits were a deliberate effort to misinform and that the agency’s pages were among the clearest public explanations of the science. Former NOAA administrator and Oregon State oceanographer Jane Lubchenco called the move “outrageous,” arguing the public has a right to clear information about risks that affect health and safety. Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academy of Sciences, emphasized that decades of NASEM reports confirm the overwhelming role of human greenhouse-gas emissions in recent warming. Those voices stress that omitting or downplaying the human role does not change the physical reality of greenhouse-gas–driven warming.

The agency’s public-response tone has also drawn attention. An EPA spokesperson told reporters that the agency’s priorities had shifted and used language dismissing critics as part of a “climate cult,” framing the edits as a rejection of advocacy and an emphasis on public health and economic recovery. That comment intensified the debate by signaling a political rationale alongside the content changes. Agency press statements and emails to reporters explained the edits as part of an effort to refocus pages, but did not offer detailed scientific justifications for removing explicit references to fossil-fuel combustion.

Context: a broader federal purge

Observers place the EPA action within a pattern of content changes across multiple federal agencies in 2025. Since the start of the year, watchdog groups and journalists documented similar removals or downgrades of climate content at FEMA, the Department of Transportation, and other agencies, gestures that critics say amount to an administrative campaign to obscure the scale of human-driven climate risk. Those broader removals included rebranding pages and excising the term “climate change” from URLs and headings, making it harder for the public to find consolidated federal guidance and data. The continuity of these edits across agencies has sharpened concerns about coordinated information gaps rather than isolated edits.

Consequences for health, regulation and public understanding

The stakes of how a federal agency frames the causes of climate change go beyond accuracy in an abstract sense: they affect policy, regulatory authority and public-health preparedness. EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases in the United States has historically rested on scientific findings — including endangerment determinations and assessments of the health and welfare impacts of pollution — that depend on the recognition of human-driven warming. If a central federal science account is rewritten to omit or downplay human causation, legal and administrative debates about the scope of EPA authority could be affected, and public-facing explanations that help communities adapt and prepare could be undermined. Analysts point out that acknowledging human causation is a prerequisite for many regulatory and mitigation actions; removing it from public materials creates confusion about why policy instruments are necessary.

Practically, the deletions also strip away content that local health departments and educators used to explain how climate change increases risks for children, low-income communities and people with respiratory illnesses. Without those concise summaries and linked evidence, communities facing heat waves, higher pollen seasons and vector-borne disease pressure lose a straightforward way to connect observed harms to underlying causes and interventions. Critics argue that such gaps will make it harder to build public support for measures that reduce emissions and protect vulnerable populations.

Archiving, watchdogs and what comes next

The changes immediately prompted archiving: researchers and civic technology groups raced to capture pre-edit versions of affected pages and to preserve datasets that were at risk of disappearing. The Internet Archive and other independent archives have been used repeatedly in recent years to maintain continuity of public information when official pages change, and those copies have proven critical for journalists, courts and researchers. Some critics have already called for congressional oversight and for agency officials to explain the rationale, while others have suggested litigation if the edits are part of a broader plan to remove scientific findings that underlie regulatory authority. As of December 14, 2025, those oversight and legal processes were being discussed publicly but had not resolved the content changes.

For scientists and educators the immediate task is pragmatic: find reliable sources — from primary scientific assessments and peer-reviewed literature — and rebuild accessible summaries for community use. For the public and policymakers, the episode brings into sharp relief a simple truth: the content of federal websites is not merely descriptive; it shapes what the government claims to know and what it says it can address. That makes the contest over language on an agency webpage consequential for climate policy, public health messaging, and the day-to-day choices of communities already experiencing warming-driven hazards.

What readers can do

- Check independent archives for older versions of federal pages and for data sources cited in archived material.

- Use primary scientific assessments — the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, National Academy of Sciences reviews, and peer-reviewed literature — when seeking authoritative statements about causes and impacts.

- Ask local officials whether they rely on federal summaries for hazard planning; encourage them to incorporate multiple scientific sources into public messaging and preparedness plans.

Sources

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA website)

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC reports)

- National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- Oregon State University (Jane Lubchenco, oceanography)