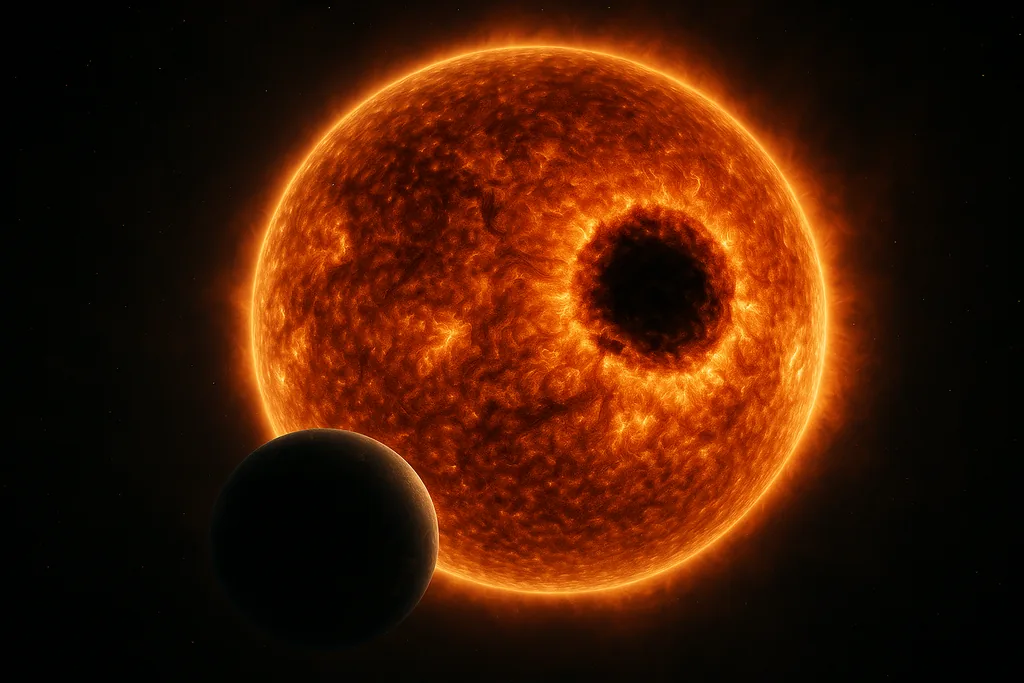

A giant dark scar on the Sun has turned to face our planet

Today a sprawling sunspot complex labelled AR 4294–4296 has rotated onto the Sun's Earth-facing hemisphere. Observers describe the feature as unusually large — roughly comparable in visible area to the group of dark magnetic knots that existed on the solar disc before the great 1859 Carrington Event — and its orientation puts Earth directly down the line of any eruptions that might follow.

The new complex is not a single blemish but a cluster of active regions whose tangled magnetic fields make them candidates for powerful flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Solar physicists are monitoring the group closely because when big active regions point at Earth the odds that a flare or CME will intersect our planet rise significantly.

Sunspots, magnetic stress and why size matters

Sunspots are cooler, darker patches on the Sun’s photosphere where intense magnetic fields break through and suppress convection. They are signposts of magnetic energy stored above the solar surface. The larger and more magnetically complex a group is, the greater its capacity to release energy suddenly in the form of a solar flare or to launch a CME — a billion-ton cloud of magnetised plasma that can take one to several days to cross the Sun–Earth distance.

Immediate impacts: auroras, satellites and timing

If the active region produces a strong CME aimed at Earth the first visible effect for most people would be aurorae appearing at much lower latitudes than usual — a bright, benign reminder that charged particles are interacting with Earth’s magnetic field. But there are layers to the threat.

- Solar flares themselves emit high-energy radiation (X-rays and extreme ultraviolet) that arrives in about eight minutes. Those bursts can instantly disturb the ionosphere and degrade high-frequency radio communications and GPS signals.

- CMEs arrive more slowly — typically one to three days after launch — and can compress Earth's magnetosphere, drive strong geomagnetic storms and induce currents in long electrical conductors. That is the mechanism that can damage transformers, cause regional power outages and change satellite orbits by puffing up the upper atmosphere.

- High-energy particles accelerated near the Sun or in shock fronts can create radiation hazards for aircraft on polar routes and for astronauts outside of the Earth's protective magnetosphere.

Operators of satellites and power grids routinely watch for precisely these signatures: a strong X‑ray flare provides minutes of warning for radio users, while coronagraphs and solar wind monitors give a day or more of lead time for CMEs — time that can be used to reorient or power down sensitive spacecraft and to brace critical grid components.

How likely is a catastrophic Carrington repeat?

It is important to separate immediate concern — a strong Earth‑directed eruption over the next days — from the idea that one giant sunspot guarantees civilisation‑ending damage. Historically, the Carrington Event of 1859 is the yardstick for a severe modern storm: auroras visible at tropical latitudes and electrical surges that tripped telegraph systems worldwide. The Carrington flare was spectacular, but the technological landscape in 1859 was narrow; today’s world is far more dependent on interconnected electronics, so a similar storm would have more widespread consequences.

That said, not every large sunspot produces a damaging CME aimed at Earth. Many big active regions remain magnetically quiet or launch CMEs in directions that miss our planet. Forecasting remains probabilistic: scientists look at the magnetic architecture, recent flare history from the region, and real‑time coronagraph imagery to estimate Earth impact likelihood and potential severity.

Historical context: Carrington, Miyake events and scale

The Carrington storm is not the largest solar event we know about. Proxy records — tree rings and ice cores — have revealed abrupt rises in cosmogenic isotopes such as carbon‑14 and beryllium‑10 that point to intense particle bombardments of the atmosphere roughly 1,250 years ago and at multiple other times. These so‑called Miyake events, named after the researcher who identified a pronounced spike in carbon‑14 in 774 CE, appear to represent particle storms at least an order of magnitude stronger than the Carrington Event.

Crucially, Miyake events are still poorly understood. They could be single, extreme superflares, or a sequence of powerful particle injections spread over months. Either way, the implications for modern electronics and satellites would be severe — far beyond the transient telegraph problems seen in 1859. Studies of fossilised trees and ice cores have pushed some of these events back tens of thousands of years, demonstrating that our Sun is capable of producing bursts that exceed the historical instrument record.

Why scientists are not sounding an alarm bell — yet

Researchers emphasise monitoring and preparedness rather than panic. The presence of a large sunspot complex increases probability, not certainty, of a strong Earth‑directed event. Forecast centres continuously analyse imagery from solar observatories and space‑based monitors that detect eruptive signatures and nascent CMEs. When a CME is observed leaving the Sun, modelled travel times and the embedded magnetic field direction determine the likely geomagnetic response.

Preparedness steps are practical and established: satellite operators can change spacecraft orientation or suspend sensitive operations; airlines can reroute polar flights; grid operators can implement temporary protections for transformers. These mitigations are most useful when forecasters can identify an outbound CME or detect a rapid stream of energetic particles.

What to watch for in the next days

- Space agencies and space‑weather centres will issue alerts if the region produces X‑class flares or launches CMEs. Those alerts carry timelines: X‑ray bursts (instant), CME arrival times (days), and particle event warnings (rapid, but with some early detection possible).

- Amateur and professional observers may start seeing enhanced auroras if the Sun erupts and the CME impacts Earth. Photographs and citizen reports often provide a first visual hint of geomagnetic activity at mid‑latitudes.

- Critical infrastructure operators will be watching official forecasts and may activate contingency procedures if the solar wind conditions indicate a strong, southward‑directed magnetic field — the configuration most effective at driving strong geomagnetic storms.

Why this matters beyond spectacular auroras

Even if this particular active region does not spawn a catastrophic storm, the episode is a reminder that solar extremes are real, rare but consequential, and that modern society has vulnerabilities that were absent in earlier centuries. The ability to detect, model and respond to solar eruptions has improved significantly in the space‑age era, but so too has our dependence on delicate electronics, global satellite systems and long high‑voltage transmission networks.

Studying large active regions today also informs long‑term resilience planning. Scientists who map past Miyake events and who study how magnetic energy is stored and released on the Sun are helping refine the scenarios engineers use to harden systems against plausible worst cases. Observations now feed models that can buy the hours and days needed to protect critical hardware and to reduce potential economic and societal harm.

Sources

- Nature (research papers on historic solar particle events and the Miyake discovery)

- Nagoya University (Miyake et al. carbon‑14 tree‑ring research)

- College de France (palaeocosmic-ray and climatology analyses)

- University of Reading (space physics commentary and modelling)

- Lund University (solar science research)

- Aix‑Marseille University (dendrochronology studies)

- ETH Zurich (solar‑activity research)

- NASA (space‑based solar observatories and space‑weather monitoring)