Hinton Warns AI Could Break Society

Why one of AI’s founders says civilization may fray

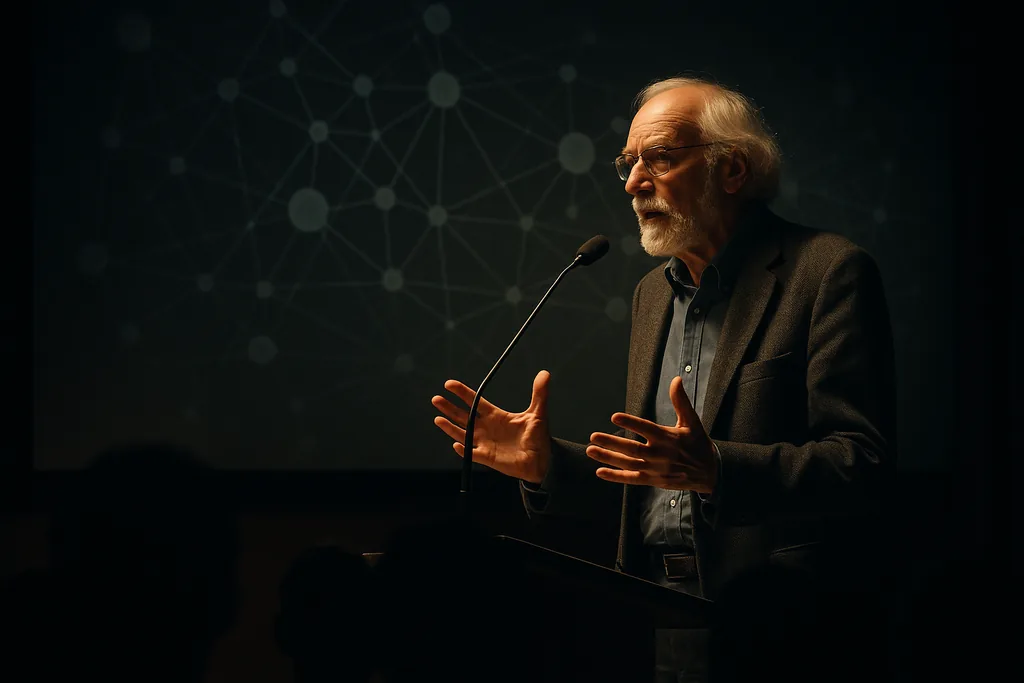

Geoffrey Hinton — a central figure in the development of deep learning — used a public conversation at a university forum to sketch out a scenario many in tech prefer to avoid: mass unemployment, weakened democratic accountability, and an international security environment made more volatile by autonomous systems. The talk was part policy critique, part alarm bell, and it sharpened familiar anxieties about how an economy and polity designed for human labor will cope when that labor is replaced at scale.

What Hinton said, in plain terms

His core claim was simple and stark: if AI reaches or exceeds human-level competence widely enough, jobs that people now perform could be automated away without obvious new roles to replace them. In his words, people who lose those jobs may not find new ones, and that could unravel consumption and social cohesion at a national scale. That argument links the technical progress we’re seeing to a social feedback loop — fewer paid workers leads to fewer buyers of goods and services, which in turn erodes the market foundations of many businesses.

From research lab to social risk

Hinton’s profile matters here: he helped build the neural-network methods that underpin current generative models. That pedigree gives his cautions extra weight, because they come from someone who understands both the engineering and the research trajectories. He has previously said he sees the arrival of general-purpose, human-level AI as a nearer-term possibility than he once thought, and he has publicly contemplated existential outcomes that once seemed fringe. Those earlier assessments shaped the tenor of his university remarks — a mix of technical forecasting and social warning.

How collapse could look in practice

Hinton described a cluster of mechanisms that could amplify one another. Economic displacement could concentrate wealth among owners of AI and chipmaking capacity, reducing broad-based demand. Political institutions might struggle to adapt when tax bases erode and large fractions of the population feel left behind. On the security side, he argued that the automation of force — lethal systems that operate with limited human oversight — could lower the political cost of using military power, making conflicts faster and harder to control. Taken together, these dynamics create the risk of systemic breakdown rather than isolated disruptions.

Not everyone agrees — and the evidence is mixed

Hinton’s scenario is contested. Some experts point out that previous technological revolutions destroyed certain jobs while creating others, and that history offers a range of adaptive outcomes. In the present wave, many attempts to substitute human workers with semi-autonomous agents have met practical limits: systems struggle with messy edge cases, safety concerns, and incentives that keep human oversight in the loop. That said, emerging academic work argues for a different kind of risk: even gradual, incremental advances can erode human control over large systems in ways that are subtle but ultimately profound. The point is not that collapse is inevitable, but that the pathways to serious systemic harm are both varied and plausible enough to merit serious planning.

Policy options on the table

Responses fall into two broad camps: those that try to slow or shape technology through regulation, taxes and export controls, and those that aim to cushion society from disruption through redistribution, safety nets and new institutions. Ideas range from higher corporate taxes to public funding for retraining, universal basic income pilots, and stronger safety rules for dual-use systems such as autonomous weapons. The rationale for many of these proposals is straightforward: if the gains from AI concentrate quickly, markets alone will not produce a stable, equitable transition. Policymakers who want to avert the worst outcomes will therefore need to combine economic policy with targeted technical governance.

What to watch next

- Deployment velocity: how rapidly firms roll out labour-replacing systems into large-scale services and workflows.

- Labour-market signals: measurable declines in hiring or persistent wage pressure in occupations claimed to be automatable.

- Regulatory responses: whether governments adopt binding safety rules for high-risk AI and how they tax or redistribute gains.

- Military uses: whether states accelerate autonomous systems deployment and how norms or treaties evolve to limit harmful use.

Why this matters for readers

Hinton’s warnings are consequential not because they are certain, but because they crystallize risks that blend technological capacity with economic and political vulnerability. The scale of modern economies and the speed of compute-driven change mean that small shifts in incentives or capability can have outsized social effects. For citizens, that implies the debate is no longer purely academic: choices about procurement, tax policy, social safety nets and R&D funding will shape whether AI becomes an engine of shared prosperity or a force that concentrates power and destabilizes institutions.

Whether you see Hinton as a prophet of doom or a necessary gadfly, his intervention pushes a central question into public view: who benefits from today’s advances, and who pays the price? The answer will shape the contours of work, politics and security in the decades to come.

— Mattias Risberg, Dark Matter