Mission concept aims to image the razor‑thin photon ring around black holes

Mission concept aims to image the razor‑thin photon ring around black holes

The photon ring is an extremely narrow, orbital feature of light that grazes a black hole before escaping to distant observers. Detecting and resolving this ring would provide a direct probe of the spacetime geometry near the event horizon and enable precision tests of general relativity.

What the photon ring is, in plain language

The photon ring consists of light rays that have executed one or more partial or full orbits near the black hole before reaching a telescope. Its radius and shape depend primarily on the black hole’s mass, spin and the surrounding spacetime rather than on the details of the emitting gas, so the feature encodes robust information about the compact object.

The scientist making it a mission

Alex Lupsasca, a theoretical physicist who has studied the photon ring’s properties, is a visible advocate for direct imaging of the ring. He argues that confirming the ring and demonstrating its orbital-photon origin would constitute strong evidence that the imaged compact object behaves like a black hole as described by general relativity. He is the project scientist for a proposed mission concept that would pair a radio telescope in Earth orbit with ground arrays to achieve much greater resolving power.

Why existing arrays fall short

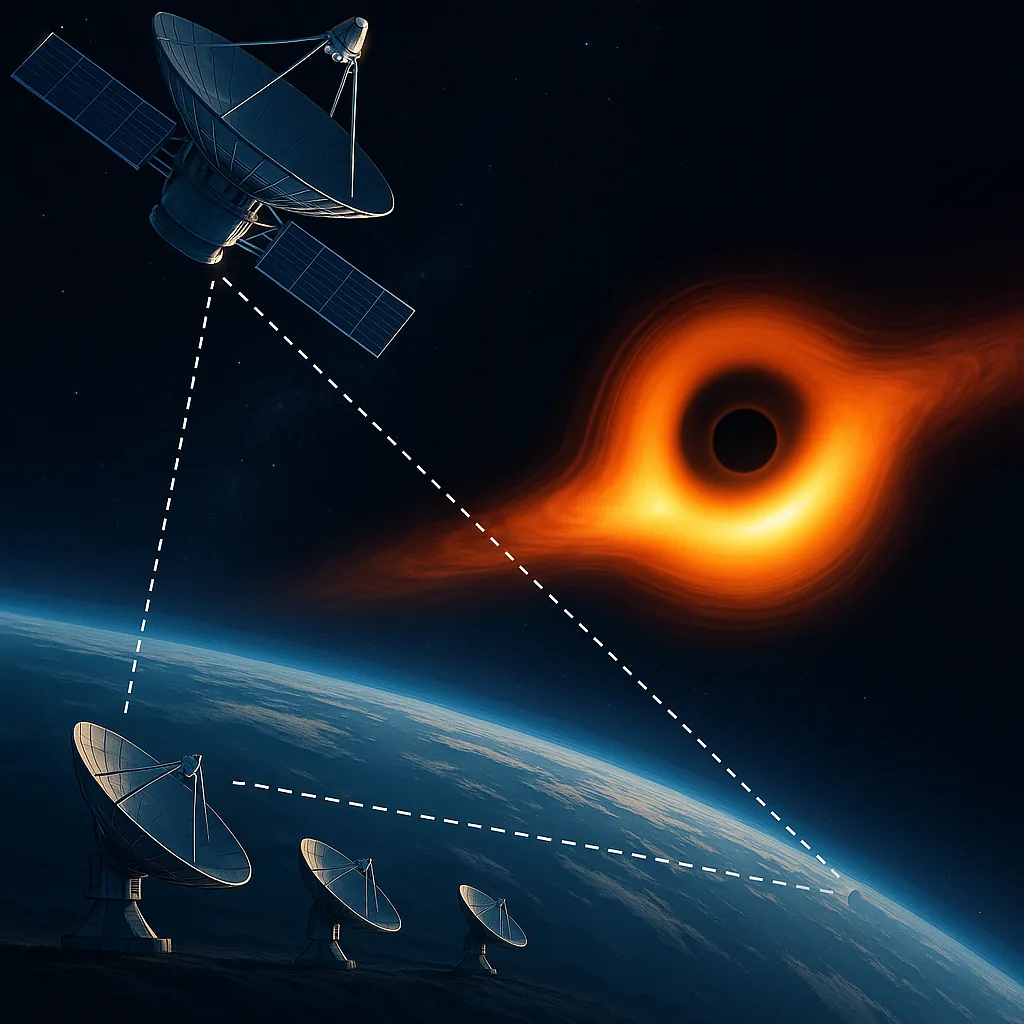

Ground-based very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) combines radio dishes around Earth to emulate a telescope the size of the planet and delivered the first horizon-scale images. However, the photon ring’s width at relevant millimetre and submillimetre wavelengths is far below the angular resolution of current arrays. The ring is both very narrow and carries less flux than the broader emission, making it vulnerable to small calibration errors, atmospheric noise and sparse baseline coverage. Extending baselines into space and improving sampling of the interferometric visibility function is the clearest route to resolving this fine substructure.

From blueprint to baseline: the Black Hole Explorer

The Black Hole Explorer (BHEX) concept proposes launching a modest radio dish into medium Earth orbit to join ground millimetre arrays. Operating roughly between 100 and 300 gigahertz, a single satellite would increase maximum baseline lengths and fill gaps in baseline coverage. That improved Fourier-domain sampling enhances resolving power and sensitivity to the faint, high‑frequency oscillations produced by photon subrings. Mission planners have suggested an early‑2030s target for launch and aim to observe the two most accessible targets: the supermassive black hole in the galaxy M87 and the one at the center of the Milky Way.

How a thin line tests fundamental physics

Because the photon ring’s geometry depends weakly on emission details, its measured radius and shape can be compared to predictions for a Kerr black hole. Deviations could indicate new physics or unexpected near‑horizon structure. Recent theoretical work has clarified which observables—such as demagnification rates between subrings, time delays, and angular structure tied to spin and inclination—would be diagnostic of departures from the Kerr solution.

Between theory and practice: signal, polarization and noise

Even with adequate baselines, practical issues remain. Subimages forming the photon ring can interfere; polarization may be reduced depending on magnetic field geometry; and radiative transfer through turbulent plasma can blur features. Simulations that combine general‑relativistic magnetohydrodynamics with radiative transfer find that the photon ring can be relatively depolarized in some emission regimes, but also that its visibility on particular baselines carries predictable signatures. Those model predictions guide the design of baseline schedules and data‑analysis strategies to extract the faint ring signal.

What success would mean

Resolving the photon ring would elevate black‑hole imaging from qualitative pictures to precision measurements. A detected ring would enable more direct determinations of mass and spin, tighter tests of whether near‑horizon spacetime matches the Kerr metric, and dynamic studies based on timing of subring signals. Stacking timing signatures could reveal light‑travel delays and motions near the photon orbit—measurements that probe gravity in its most extreme regime.

The long view

Imaging the photon ring is technically demanding and requires sustained investment in instrumentation, close coordination between space and ground assets, and ongoing interaction between theory and observation. Nevertheless, simulations and interferometric theory now outline concrete targets, and mission concepts show plausible ways to build the necessary baselines. For proponents, the campaign is a logical next step: not just to image a black hole’s silhouette but to decode the geometric imprint left by light skimming the horizon.