World's largest neutrino detector posts spectacular early results

The Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO) has released its first physics results after two months of operation, delivering the most precise measurements yet of key neutrino oscillation parameters and hinting at a lingering tension between solar and reactor neutrino data.

On November 19–20, 2025, the team behind the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO) unveiled the experiment's first physics findings — and they arrived far sooner than many scientists expected. With less than two months of effective running time, JUNO has already produced measurements of two fundamental neutrino parameters with better precision than the global record built up across decades of experiments.

What JUNO is and why it matters

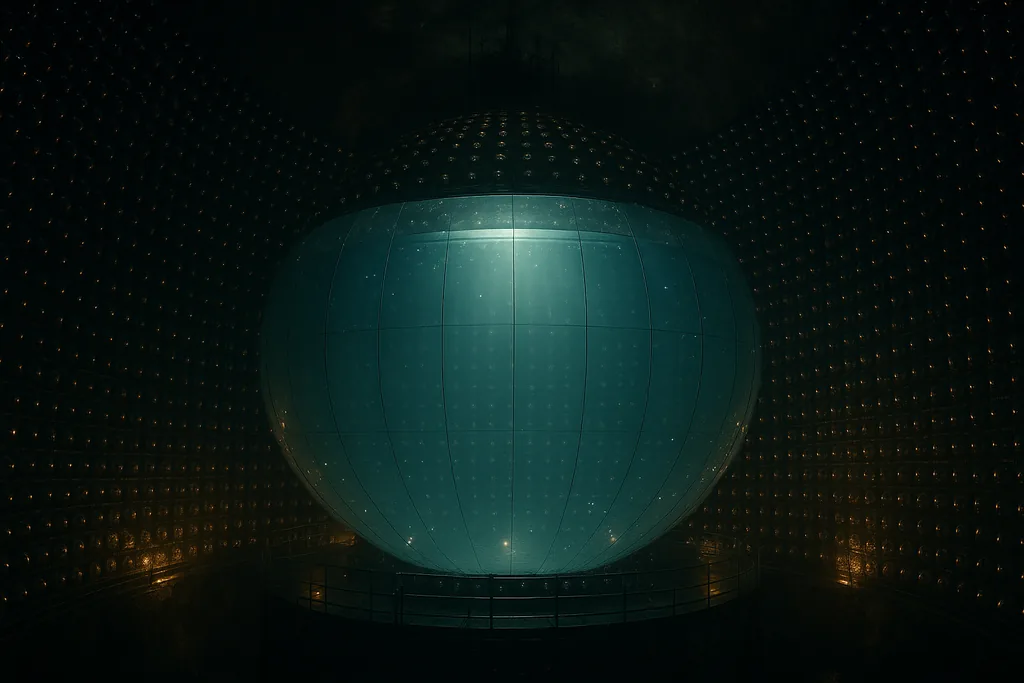

JUNO is a next‑generation, large liquid‑scintillator detector sunk roughly 700 metres beneath a granite overburden in Jiangmen, Guangdong province. Its central element is a 35.4‑metre acrylic sphere holding about 20,000 tonnes of ultra‑pure scintillating fluid, observed by roughly 40–45 thousand photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) mounted inside a 44‑metre water pool that provides shielding and muon tagging. The instrument began physics data taking on August 26, 2025, after more than a decade of design and construction.

Neutrinos are famously elusive particles: trillions stream through each of us every second yet almost never interact. That rarity is precisely why massive detectors like JUNO are needed. When a neutrino does interact in the scintillator it creates a faint flash of light; sensitive PMTs pick up the light and allow physicists to reconstruct the neutrino's energy and identity. JUNO's size and custom photodetectors make it the most sensitive facility in the world for low‑energy neutrinos produced by nuclear reactors and other sources.

Early harvest: precision after 59 days

The collaboration analysed data taken between August 26 and November 2, 2025 — an effective dataset of 59 days — and reported measurements of the solar mixing angle (θ12) and the smaller solar mass‑splitting (Δm2_21). Using about 2,400 reactor‑antineutrino events collected in that period, JUNO achieved roughly a 1.6‑times improvement in precision over the combined previous measurements of the same parameters.

Those two numbers are cornerstones of the three‑flavour neutrino oscillation framework: θ12 governs how electron neutrinos mix with other flavours at low energies, and Δm2_21 sets the frequency of the oscillation driven by the difference in the squares of two neutrino masses. Improving the precision on these quantities sharpens every downstream test of neutrino behaviour, from mass ordering searches to studies of neutrinos from the Sun and supernovae.

A persistent tension: solar versus reactor results

One striking aspect of JUNO's early analysis is that it confirms a mild but persistent mismatch — about 1.5 standard deviations — between θ12 and Δm2_21 values extracted from solar neutrino experiments and those obtained from reactor neutrino experiments. This 'solar‑reactor tension' has been visible at low significance in global fits for several years; JUNO's high‑precision reactor measurement reproduces the difference rather than smoothing it away.

That is important because if the tension increases with improved data it could be a sign of physics beyond the three‑flavour oscillation model — for example, nonstandard neutrino interactions, exotic sterile states, or subtle issues in solar modelling. Alternatively, it could point to underestimated systematic uncertainties in one or more experimental approaches. JUNO is uniquely positioned to resolve that ambiguity because the detector will measure both reactor and solar neutrinos within the same instrument and with the same calibration systems.

Why neutrinos are a portal to new physics

Neutrinos already forced a rethink of the Standard Model when oscillations implied they have mass — a fact the original formulation of the Standard Model did not predict. The pattern of masses and mixings is unusual compared with other fermions and may encode clues about how mass is generated at high energy scales. Pinpointing oscillation parameters with precision opens a window on tiny deviations from the three‑flavour paradigm that could signal new forces, new particles or connections to the matter–antimatter asymmetry of the universe.

JUNO's long‑term program goes well beyond the first two parameters. The collaboration aims to determine the neutrino mass ordering (whether the third mass state is heavier or lighter than the other two), push many oscillation parameters to sub‑percent precision, detect neutrinos from the next nearby supernova, measure geoneutrinos that probe Earth’s interior, and search for rare processes that would directly break the Standard Model.

Technical achievement and scale

Pulling off the early results required more than a large tank. JUNO incorporates several technological breakthroughs: a highly transparent, ultra‑clean scintillator that lets light travel far without scattering; large, high‑efficiency PMTs designed to capture faint flashes; and a comprehensive calibration system to map detector response precisely across the entire 35‑metre sphere. Together, these systems let scientists separate true neutrino events from backgrounds and measure energies with the fine resolution necessary to extract oscillation effects.

What comes next

- Mass ordering. Determining whether the three neutrino mass states are arranged 'normal' or 'inverted' is a primary JUNO goal and will take a few years of data at full sensitivity.

- Solar neutrinos inside JUNO. Using the same detector to measure both reactor and solar neutrinos will let JUNO test whether the observed solar‑reactor tension is an experimental artefact or a genuine physical anomaly.

- Broader searches. With accumulating exposure, JUNO will probe for deviations from the standard oscillation picture, look for sterile neutrinos at certain mass scales, and be ready to capture the neutrino burst from a galactic supernova should one occur.

How the field will react

New experiments rarely rewrite textbooks on day one, but JUNO's initial performance is the textbook the field wanted to see: the detector is doing what it was designed to do and delivering world‑leading precision right away. The confirmation of the solar‑reactor tension will provoke scrutiny and new cross‑checks, and it will inspire theorists to revisit models that could produce such an effect. Over the next several years, JUNO's steady stream of high‑quality data will either resolve this tension or push it into a statistically significant anomaly that demands new physics.