A bright flash from the Cosmic Dawn

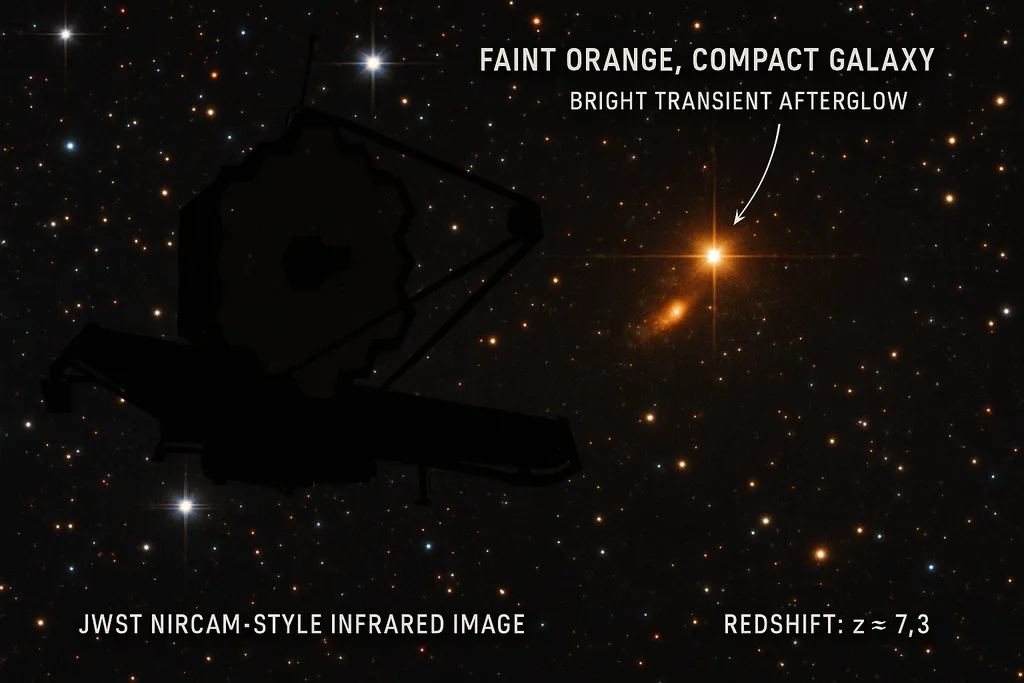

On 14 March 2025 a satellite called SVOM registered a brief, very bright flash of gamma rays — a long gamma‑ray burst that would later be catalogued as GRB 250314A. Within hours telescopes on the ground and in space swung to the location. Follow‑up observations identified an infrared afterglow and, crucially, a very high redshift: about 7.3. That combination put the explosion deep into the era astronomers call the Cosmic Dawn, when the universe was only about 730 million years old. A coordinated campaign of observations, including imaging with the James Webb Space Telescope, has now identified the burst as the electromagnetic signature of a supernova — the earliest such explosion seen so far.

How the discovery unfolded

Gamma‑ray bursts (GRBs) are split into two broad families: short events of under two seconds, usually linked to compact mergers, and long events lasting longer than two seconds that are associated with the deaths of very massive stars. SVOM’s detection on 14 March displayed the temporal and spectral characteristics of a long burst. Within days observers using the Nordic Optical Telescope secured an infrared afterglow and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope measured a redshift near 7.3, placing the source at a lookback time of about 13.07 billion years.

Surprising familiarity at the Universe’s first billion years

One of the most striking outcomes is how ordinary the supernova appears. Early in the universe, stellar populations are expected to have been poor in heavy elements (astronomers call them metals) and to behave differently from stars that form today. Yet the explosion associated with GRB 250314A shows photometric and spectroscopic signatures that resemble modern core‑collapse supernovae linked to long GRBs: a bright, broad peak in the infrared light curve and spectral shapes consistent with the shock‑driven ejection of a massive star’s outer layers.

"We went in with open minds," said one of the team members involved in the JWST observations. "And lo and behold, Webb showed that this supernova looks exactly like modern supernovae." That apparent normality is valuable because it means models calibrated on nearer, better‑studied explosions can be a starting point for interpreting events at very high redshift. At the same time, it raises questions about how rapidly early generations of stars produced heavy elements and whether the first massive stars could yield explosions with properties similar to later populations.

What astronomers can learn from a single distant blast

Even a solitary event at z ~ 7.3 is scientifically rich. First, a long GRB provides a direct link between massive‑star death and cosmic star formation at an epoch when galaxies were small and faint. The GRB afterglow acts like a flashlight that briefly backlights the host galaxy, enabling measurements of its gas content, metallicity and dust — parameters that are otherwise almost impossible to obtain at this distance.

Second, the fact that JWST could detect and characterise the supernova means future GRB afterglows at similar or even greater distances can be used as probes of the earliest star‑forming systems. That helps constrain how early the universe became chemically enriched by successive generations of supernovae — a process that seeds later stars and planets with the elements necessary for complex chemistry.

Third, the apparent similarity to modern explosions provides data points for models of massive‑star evolution in low‑metallicity environments. If early massive stars produce collapses and jets that look familiar, theorists must reconcile that with expectations from stellar structure and mass loss at low metallicity, where winds are weaker and envelopes differ.

Observational reality and caveats

Interpreting a single high‑redshift event requires caution. GRBs are strongly beamed phenomena: we only detect bursts whose relativistic jets point close to our line of sight. That selects a special subset of massive‑star deaths and may bias any sample of distant explosions toward progenitors that produce powerful, narrowly collimated jets. In addition, the faintness of objects at z > 7 and the necessity of rapid, deep follow‑up make the observed sample small. The conclusion that early supernovae can look like modern ones is robust for this event, but whether it applies to the population as a whole will need more detections.

There are also practical limits from time dilation and redshifting. The same cosmological stretching that helps move the explosion into JWST’s spectral window also slows its apparent evolution for Earth observers: an event that might last weeks in the host galaxy’s frame can take months or longer to play out in our telescopes. This makes coordinated monitoring across months essential to capture the full light curve and spectral evolution.

Next steps for studying the first explosions

The result underlines a recurring theme in the JWST era: the telescope is not only revealing surprisingly luminous, compact galaxies near the cosmic dawn, it is also allowing astronomers to study transients that trace the lives and deaths of the first generations of massive stars. Teams are already planning continued monitoring of GRB afterglows, and new transient surveys and next‑generation facilities will expand the discovery space. In particular, more high‑redshift GRBs plus JWST follow‑up — and, in time, observations with 30‑metre class ground telescopes — will build a statistical sample that can be compared to models of stellar evolution, nucleosynthesis and early galaxy assembly.

For now, GRB 250314A offers a vivid proof of concept: with fast discovery, rapid ground‑based spectroscopy to secure a redshift, and sensitive infrared follow‑up, astronomers can catch and dissect the deaths of the universe’s earliest massive stars. Each such detection stretches our ability to test models of the first billion years, and this one — at an age of just 730 million years after the Big Bang — is the earliest supernova yet seen.