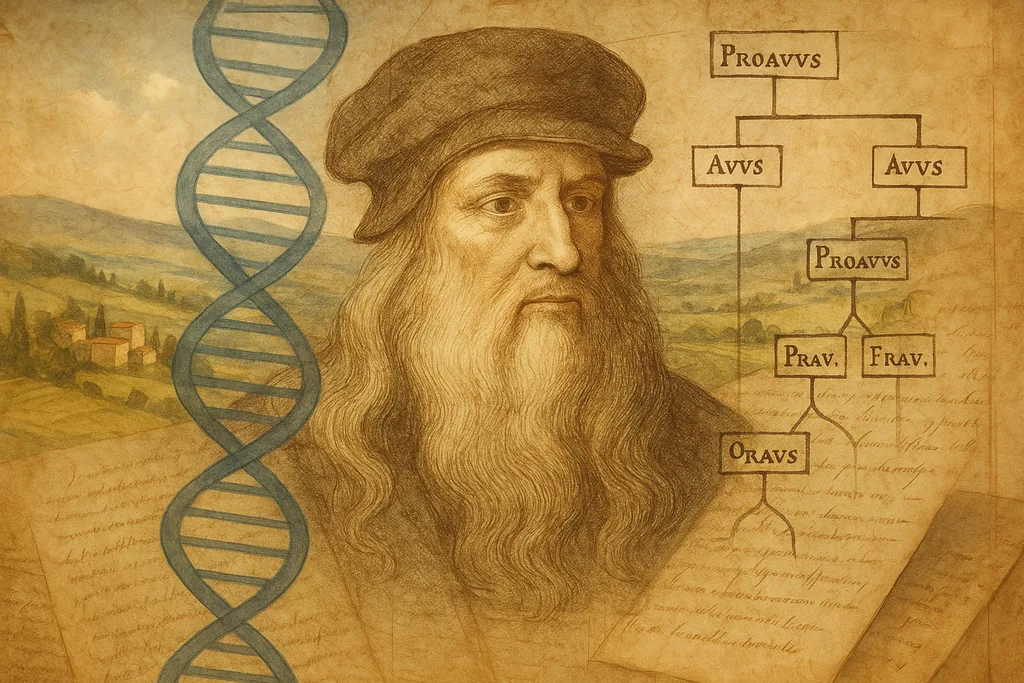

Leonardo’s DNA: A 21‑Generation Breakthrough

Six living men, one long genetic thread

For the first time, researchers have tied parts of Leonardo da Vinci’s patrilineal legacy to living people. A freshly published volume documenting three decades of archival and genetic work reconstructs a family tree that reaches back to 1331 and follows a continuous male line through 21 generations. The book presents a list of more than 400 individuals in the reconstructed pedigree and identifies a subset of direct male‑line descendants who could help establish a genetic baseline for the artist’s Y chromosome.

What researchers actually tested

The research team combined traditional genealogy with molecular tests. After mapping branches of the da Vinci family using municipal and church records, historians and geneticists collected DNA from volunteers in the male line and ran Y‑chromosome analyses. In laboratory tests on six contemporary men, segments of the Y chromosome matched across the tested individuals — evidence that they share a patrilineal ancestor. That result corroborates the continuity of this male line back through many centuries, at least from the later medieval period onward.

How this project grew out of earlier work

This effort stands on a foundation laid earlier in the decade, when a peer‑reviewed genealogical study documented 21 generations of the da Vinci patriline and reported multiple living male relatives. That 2021 research assembled the documentary tree and pointed to dozens of potential matches; the new book and tests represent the next phase — moving from paper genealogy to molecular verification.

Why the Y chromosome matters — and what it cannot tell us

The Y chromosome is a natural target for patrilineal investigations because it passes from father to son with relatively few changes over many generations. Matching stretches of Y‑DNA among living men indicates a shared direct male ancestor and makes it possible to draw a genetic thread back toward historical figures who left no direct offspring. But the Y chromosome is only a small part of human heredity: it represents a single paternal line and carries limited information about traits, health, or the complex genetics underlying cognition and artistic ability. In other words, a matched Y profile can authenticate a patrilineal link, but it cannot by itself explain why Leonardo looked, thought, or produced the work we study today.

Where the elusive 'Leonardo genome' could come from

Confirming a living patrilineal line is a crucial step but not the finish line. Researchers now aim to compare modern Y profiles with genetic material recovered from historical sources tied to Leonardo himself — for example bone fragments historically associated with his burial sites, preserved hair, or biological traces on manuscripts and artifacts. If authentic ancient material can be obtained and yields retrievable DNA, it could be compared against the living baseline to test whether the remains are Leonardo’s and to anchor genetic inferences more securely to the man who died in 1519. Doing this requires meticulous sampling, specialist ancient DNA facilities, and permissions from cultural‑heritage authorities.

The technical and ethical hurdles

- Authentication and contamination: Ancient DNA work is vulnerable to modern contamination and chemical damage to old molecules. Laboratories use characteristic damage patterns and multiple controls to distinguish genuine ancient sequences from modern intruders, but samples from historic burials or objects are often degraded and sparse.

- Interpretation limits: Even a full Y‑chromosome match or a partial ancient genome does not reveal complex behavioral traits. Genetics may illuminate predispositions to certain health conditions or aspects of metabolism and appearance, but environment, culture and training shaped Leonardo’s life and work in ways DNA cannot record.

- Consent and privacy: Living descendants have privacy rights and legitimate concerns about publicity. Scientists must balance public interest in a historic figure with the dignity and autonomy of present‑day people who provide samples.

- Cultural‑heritage permissions: Exhuming or sampling remains — especially those in nationally important sites — requires legal authorization and ethical review. For figures like Leonardo, whose legacy is globally significant, access decisions involve museums, churches, state authorities and often public debate.

Why historians and scientists are cautious but excited

The work combines disciplines rarely brought together at this scale: archival history, field archaeology, forensic anthropology and modern molecular genetics. When done carefully, it can resolve long‑standing questions about identification of remains, correct errors in the historical record, and provide small but meaningful biological context for a major cultural figure. Experts emphasise that the most realistic outcome is not a simple 'genius gene' but a clearer, evidence‑based picture of ancestry, certain hereditary conditions, and the physical attributes that can be reconstructed from DNA.

What happens next

In the short term, the immediate scientific objective is replication and extension: test more putative male‑line descendants, expand Y‑chromosome profiles with higher‑resolution markers, and seek authenticated ancient material that can be sequenced under strict contamination controls. Parallel efforts will press on with ethical review, public communication and negotiation with heritage bodies to establish whether human remains or other artifacts may be sampled. The project’s progress — from paper trees to genetic confirmation to possible ancient DNA matches — offers a rare example of how historical scholarship and modern genomics can interact.

A cautious conclusion

Reconstructing Leonardo da Vinci’s genetic heritage across 21 generations is an impressive feat of documentary and genetic detective work. It delivers a rigorous patrilineal scaffold that can support future molecular comparisons, but major technical, interpretive and ethical constraints remain. Real breakthroughs will come only if ancient samples yield high‑quality DNA and if researchers resist simplistic narratives about genius. The most valuable outcome may not be a tidy genetic explanation for creativity, but a better‑documented, more nuanced understanding of the man behind the notebooks — one that combines archival truth, measured genetics and the historical context of a life that continues to fascinate the world.

— Mattias Risberg, Cologne