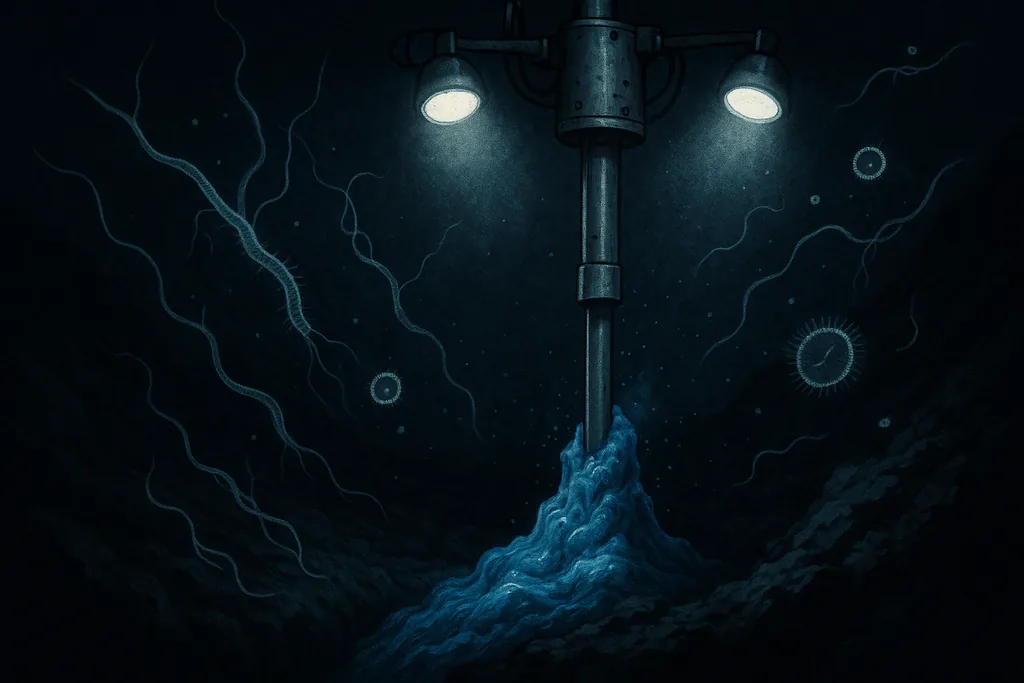

Life Found in the Ocean’s Deadly Blue Goo

Strange blue mud, strange survivors

On a recent deep‑sea expedition scientists pulled up a five‑foot sediment core of vivid blue, serpentinite mud from a cluster of mud volcanoes in the Mariana forearc and found something unexpected: chemical traces that look very much like life. The signals come not from intact genomes but from lipid molecules — fats that form cell membranes — and they point to communities of microbes eking out an existence in a world of rock, hydrogen and near‑bleach alkalinity.

The research team published a detailed study reporting these lipid biomarker results and the geological context of the samples, describing the environment as a chemosynthetic, serpentinite‑dominated biosphere beneath the seafloor.

What is this "blue goo"?

The goo is a form of serpentinite mud produced when seawater reacts with ultramafic igneous rock during subduction and alteration processes. Where silicon‑poor, magnesium‑rich rock reacts with water, the products can include brucite and other minerals that give the mud a striking blue‑green tint. These deposits are pushed upward through mud volcanoes and can form localized pockets of highly alkaline sediment on the seafloor.

Analyses from the recovered core show the mud’s pore waters reach extremely high pH — roughly around 12 — and contain very low concentrations of organic carbon and nutrients, making it one of the most chemically hostile habitats known for life. In such conditions, conventional methods for detecting DNA often fail because cell numbers are tiny and genetic material degrades; the team therefore turned to more resilient chemical fossils: membrane lipids.

How scientists make a case for life without DNA

Lipid biomarkers are hydrocarbons and modified fats that derive from cell membranes and remain detectable long after other biomolecules decay. Different groups of bacteria and archaea produce characteristic lipids; combined with carbon isotope measurements and mineral context, those molecules can reveal which metabolisms were active and whether the material is modern or relict. In this study, researchers identified lipid signatures consistent with methane‑ and sulfate‑metabolizing microbes — metabolisms tied to the chemical energy available in serpentinite systems.

Crucially, the isotopic patterns and molecular preservation suggest a mixed record: some lipids reflect living or recently living populations, while others record older, fossilized communities that were active in the geological past. That combination implies the mud volcanoes can host episodic or sustained microbial activity despite extreme pH and scant organic food.

Where the samples came from and why they matter

The cores were collected during a 2022 cruise of the research vessel that explored the Mariana forearc — a tectonically active region where oceanic crust is forced beneath another plate. The cruise discovered previously uncharted mud volcanoes and recovered the blue mud that was later analyzed in terrestrial laboratories using high‑sensitivity mass spectrometry and isotope techniques. The team has also publicly archived much of the raw data to enable independent follow‑up.

Why does this matter beyond curiosity about an odd color on the seafloor? Serpentinite environments produce hydrogen, methane and strongly reducing chemistry — a kind of chemical free lunch for microbes that do not rely on sunlight. Because similar rock‑water reactions probably occurred on early Earth, and may occur on other worlds that have liquid water and ultramafic rocks, these mud volcanoes are looked to as modern analogues for primordial habitats and potential astrobiological refuges. The new biomarker evidence strengthens the idea that chemosynthetic life can thrive, or at least persist, in places once thought sterile.

Not a monster — but still an extraordinary ecosystem

Popular descriptions that call the material a "deadly goo" or an "alien blob" are evocative but can mislead: the sediment itself is chemically extreme but it is not a self‑replicating organism. The term captures public imagination, and for good reason — the blue mud is visually dramatic and the discovery challenges easy assumptions about habitability — yet the scientific claim is precise: molecular remnants indicate microbial metabolisms tied to serpentinization, not some novel macroscopic 'goo' creature. The microbes implicated are microscopic and chemotrophic, using inorganic electron donors and acceptors rather than photosynthesis.

Next steps: growing microbes and mapping a hidden biosphere

Broader implications: carbon cycling and habitability

Keeping the wonder, cutting the hype

The discovery of lipid biomarkers in blue serpentinite mud is an elegant example of detective work at the boundary of geology and microbiology: when one class of biosignature is too faint to detect, another — chemically more robust — can reveal hidden life. It is also a reminder that extreme environments are laboratories for understanding life's resilience and its potential origins. As follow‑up studies cultivate microbes, measure in situ chemistry, and extend the survey to other forearc systems, we'll get a clearer picture of how widespread these communities are and what they mean for Earth's deep biosphere and astrobiology.

For now, the message is clear: the ocean still hides environments that defy expectations, and the blue goo at the Mariana forearc is less a monster and more a window into life pushed to the edge.

James Lawson is an investigative science and technology reporter at Dark Matter. He holds an MSc in Science Communication and a BSc in Physics from University College London and covers space, AI and emerging technologies from the UK.