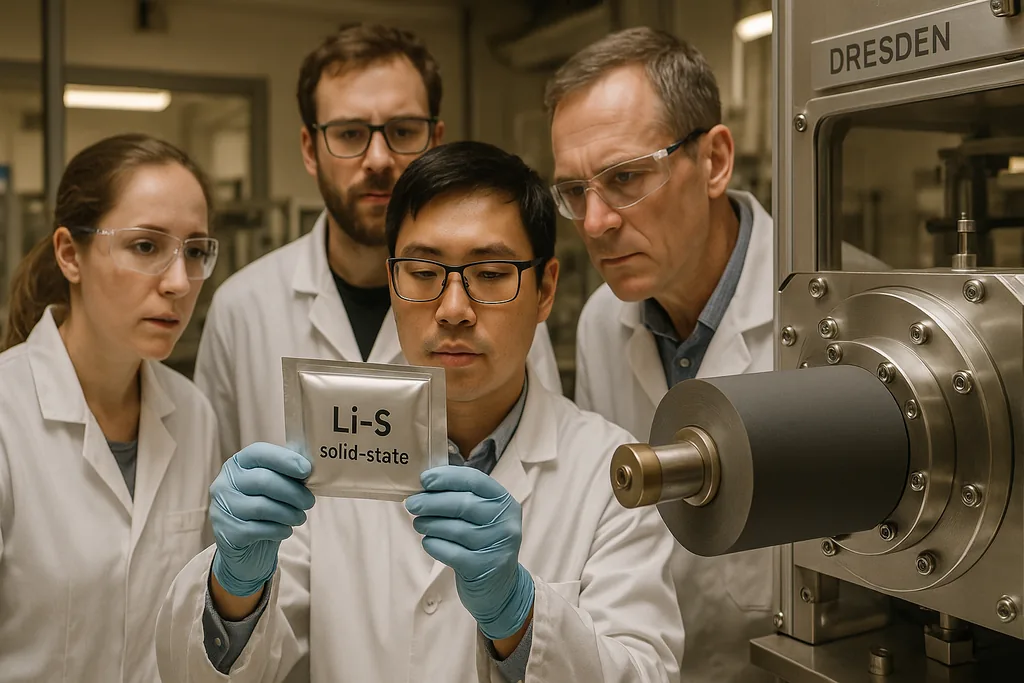

Fraunhofer's lithium–sulfur advance

This week a team at the Fraunhofer Institute in Dresden unveiled laboratory results for a next‑generation solid‑state lithium–sulfur (Li–S) battery that push energy density into a new range for transport applications. In early tests the researchers report specific energies above 600 watt‑hours per kilogram — considerably higher than most commercial lithium‑ion cells — and say their aim is to reach roughly 550 Wh/kg in commercialised cells at costs below about $86 per kilowatt‑hour. The announcement is framed inside two coordinated R&D efforts funded at national and European level, and the group says the combination of materials and a solvent‑free coating process could make the technology compatible with existing battery manufacturing lines.

A persistent chemistry problem

Lithium–sulfur designs have long been attractive on paper because sulfur is abundant, cheap and offers a high theoretical capacity — roughly double the gravimetric energy of typical lithium‑ion cathode chemistries. In practice, however, Li–S batteries have struggled to survive many charge cycles. The principal culprit is the so‑called polysulfide shuttle: intermediate sulfur species dissolve into the electrolyte during cycling, migrate to the anode, and trigger side reactions that rapidly drain capacity and shorten life. Conventional cells use liquid electrolytes that make that dissolution and migration easier, so stabilising the active materials has been the show‑stopper for decades of Li–S research.

How the Fraunhofer approach works

That practical detail matters for two reasons. First, solid electrolytes offer a physical barrier that can limit the mobility of dissolved sulfur species, lowering capacity fade. Second, solvent‑free processing reduces manufacturing energy and CO2 emissions, and — according to the team — can be adapted to existing lithium‑ion production lines rather than forcing a complete factory rebuild. The research is being advanced through two programmes: a national German initiative called AnSiLiS and a European Horizon Europe project named TALISSMAN, both of which target overcoming Li–S barriers for transport and industrial use.

What this could mean for electric vehicles

If the reported energy densities survive scaling and real‑world testing, the implications for electric mobility would be significant. Higher gravimetric energy lets designers either extend driving range for a given vehicle mass or reduce battery weight while holding range constant. Lighter vehicles accelerate more efficiently, place less long‑term load on suspension and tires, and can charge faster because there is less mass to replenish. In practical terms, cells in the 500–600 Wh/kg band at pack level could yield passenger cars with ranges well above current mid‑range models while cutting raw material demands per kilometre.

There are environmental and supply‑chain upsides too. Sulfur is a byproduct of fossil‑fuel refining and is orders of magnitude more abundant than cobalt, nickel or some other battery metals. A shift to sulfur‑heavy cathodes would reduce reliance on scarce critical raw materials and potentially lower costs. The Fraunhofer team also points to the DRYtraec process cutting production energy and CO2 output by up to around 30% compared with conventional wet coating routes — an early sign that a Li–S future might also be greener at scale.

Manufacturing, emissions and cost

One attractive claim from the Dresden work is compatibility with current lithium‑ion manufacturing infrastructure. Retrofittable processes are industry‑friendly: factories could be repurposed faster and with lower capital expenditure than building wholly new lines around exotic processes. The researchers have set an explicit commercial target — approximately 550 Wh/kg at costs under $86/kWh — that, if achieved, would be competitive in the EV market where cost per kilowatt‑hour remains a central buyer metric.

Lower cell costs and lighter systems together would reduce the total cost of ownership for EV buyers and alleviate some pressures on charging infrastructure, because lighter cars accelerate and decelerate more efficiently and therefore draw less peak power during driving cycles. That said, the path from lab to assembly line is also a path from idealised performance to the messy realities of yield, quality control and long‑term durability.

The roadblocks: cycling, scaling and safety

Laboratory specific‑energy figures are an important milestone, but they are not the whole story. Early results rarely capture pack‑level engineering losses, high‑rate charging behaviour or calendar life under automotive temperature swings. Li–S cells must also deal with mechanical stresses: sulfur changes volume as it reacts, and solid electrolytes themselves must maintain ionic contact despite expansion and contraction. Interface resistances between solid electrolyte and electrodes can also limit power delivery.

Safety is another area needing exhaustive testing. Solid electrolytes are often touted as inherently safer than flammable liquid electrolytes, but every new material and stack geometry introduces new failure modes. Automotive certification demands thousands of hours of accelerated cycling, puncture, thermal runaway and crash tests before a battery chemistry can be trusted in millions of road vehicles.

Funding, timelines and next steps

The Fraunhofer group is advancing the work within funded research consortia: a national German programme (AnSiLiS) and a European Horizon Europe project (TALISSMAN). Those frameworks are explicitly aimed at translating lab chemistry into demonstrators and pilot production. The team says full prototypes are expected in the coming years; commercial ramping will depend on whether the cells can hit required cycle life, safety metrics and manufacturing yields while staying within the cost envelope they propose.

This is not a lone‑lab effort. Industry adoption will require battery manufacturers, carmakers and equipment suppliers to validate the materials at scale, adapt electrode‑coating lines where necessary and build pilot packs for vehicle testing. Regulators will also need to assess the long‑term safety profile. If those boxes are ticked over the next few years, Li–S solid‑state cells could become an entirely new option in the EV toolkit — complementing incremental improvements in lithium‑ion and the growing interest in other chemistries.

For now, the news from Dresden is a technical step forward rather than a finished product. It revives an old promise — sulfur’s high energy per kilogram — with a modern processing twist. The real test will be longevity and manufacturability: whether the cells still perform after thousands of kilometres, repeated fast charges and the real‑world stress of heat and cold. If they do, automakers and buyers alike will feel the practical impact; until then the announcement is an encouraging, carefully‑qualified waypoint on a long, expensive road to automotive adoption.

Sources

- Fraunhofer Institute for Material and Beam Technology (Fraunhofer IWS), Dresden (research on solid‑state lithium–sulfur cells and DRYtraec processing)

- AnSiLiS project (German federal research initiative)*

- TALISSMAN (Horizon Europe research project)

- DRYtraec solvent‑free coating manufacturing method (Fraunhofer IWS)