Short, precise lede

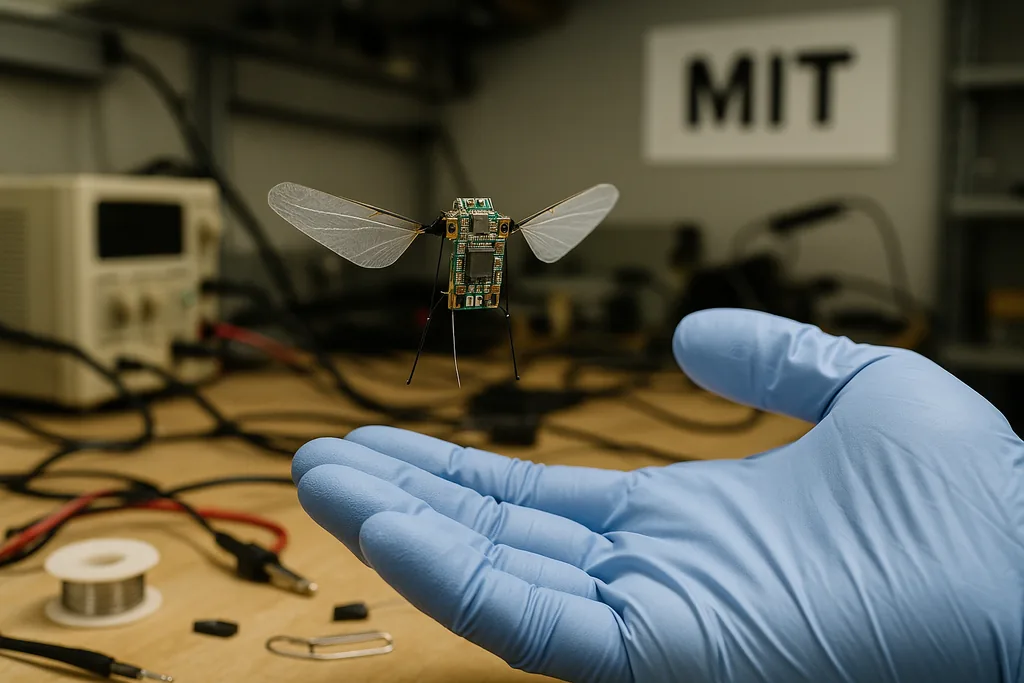

On 3 December 2025, engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology published a demonstration of aerial microrobots that fly with speed and agility approaching real insects. The experiments show bumblebee‑sized machines executing flips, fast turns and darting saccades while tolerating gusts of wind and tight, cluttered environments — performance that moves small flying robots out of lab curiosities and closer to operational utility.

A lab demonstration with troubling echoes

The research team framed the machines as search‑and‑rescue scouts: microrobots that could slip into rubble, peer through narrow gaps and find survivors where bigger drones cannot. That humanitarian rhetoric, however, sits uneasily beside the technical facts. At a paperclip or coin‑weight scale, a flight platform needs no conventional explosive payload to be lethal. A guided needle, a micro‑charge, or a biologically active agent delivered at close range would transform a scouting device into a precision weapon that is hard to detect and hard to attribute.

The immediate experimental setup was tethered and partly run from external computation; the researchers themselves acknowledge the controller currently runs offboard. But the same paper demonstrates control policies and sensor strategies that are compact and simple enough in principle to be moved onboard as processors shrink. That roadmap — from tethered demos to autonomous, untethered agents — is what turns a benign proof‑of‑concept into a potential operational capability.

Capabilities and technical leap

What the MIT team achieved is not merely miniaturization. According to the technical details disclosed, these microrobots withstand wind disturbances exceeding one metre per second, perform aggressive manoeuvres with trajectory deviation measured in centimetres, and execute rapid, insect‑like gaze shifts known as saccades. Those qualities are crucial because real‑world environments rarely offer the smooth flights assumed by earlier micro‑air‑vehicle work: crosswinds, debris and rapid obstacle appearance demand agility as much as steady thrust.

Equally important is the sensory and control architecture. The researchers compressed decision‑making into distributed, fast control loops that can stabilise the vehicle despite manufacturing tolerances and intermittent tether interference — a sign that the team designed for robustness, not just an idealised lab path. Experts unaffiliated with the work have noted that the controller’s external execution does not negate the demonstration’s import: similar policies are feasible on the reduced compute budgets available on insect‑scale hardware, meaning onboard autonomy is plausible within a foreseeable engineering timeline.

Funding and dual‑use pathways

The project’s funding footprint points to familiar dual‑use channels. Military research agencies including the Office of Naval Research and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research supported elements of the work. Those agencies routinely fund navigation, autonomy and resilience research framed as benefitting civilian relief operations; historically, the same building blocks have migrated into reconnaissance and strike systems once size, endurance and autonomy permit.

History shows how funding lines matter. When advanced mobility, sensor fusion and autonomy are developed with military collaborators, the most immediate customers and adopters are often defence organisations that can integrate the pieces rapidly. That pathway is not inevitable, but it is well trodden: technologies invented for rescue or environmental monitoring have repeatedly been repurposed, sometimes with little public debate, into capabilities for surveillance and precision engagement.

Historical precedents and institutional memory

The idea of insect‑sized espionage devices is not new. Cold War projects imagined tiny, deniable platforms for covert observation; some prototypes were fragile and wind‑sensitive, limiting their utility. The new MIT demonstrations specifically address crosswind instability — a historical failure mode — by showing robust flight in disturbed air. That technical closure of a former limitation revives questions the earlier projects left unresolved: if the engineering problems that prevented operational use are solved, what constraints remain on deployment and control?

MIT’s own institutional lineage includes labs and programs that have sat at the intersection of academic research and national security needs. That lineage is complex: it has produced life‑saving technology and also tools that were later used in controversial military operations. The current work’s mixture of humanitarian framing, defence funding and clear operational implications invites renewed scrutiny of how academic research transitions into government, contractor and battlefield use.

Policy implications and oversight

Tiny flying robots with onboard autonomy would strain existing legal, ethical and technical guardrails. Detection and attribution are harder at paperclip scale, complicating norms of state responsibility and proportionality. Sensors and countermeasures developed for larger drones are largely ineffective against platforms whose radar cross section, acoustic signature and visual footprint are minimal. That asymmetry creates incentives for covert use: a small, autonomous system could be deployed to act in ways that are difficult to trace back to an originator.

Regulatory and export regimes are currently tuned to larger, kinetic systems — missiles, armed aircraft, armed unmanned aerial vehicles — not to centimetre‑scale agents. Nor are there widely agreed international standards governing the permissible use of autonomous microrobots. Absent such frameworks, the technology’s earliest adopters will set behavioural norms by practice rather than by law, and those early adopters could be state or non‑state actors seeking cheap, deniable precision.

Technical mitigations and possible governance

Engineers and policymakers have a menu of mitigations that could reduce risk without stalling scientific progress. Design constraints that prioritise transparency and traceability — for example, mandatory broadcast beacons or tamper‑evident hardware — would make covert use more difficult. Funding agencies could require dual‑use risk assessments and formal red‑teaming before release. Research groups can adopt institutional review boards focused on security implications, and journals could require authors to include threat‑model statements in papers describing small, mobile agents.

None of these steps is silver bullet. Determined actors will seek workarounds. But building norms into the development process — and making them conditions of funding and collaboration — changes the economics and the timelines for misuse. That matters when the underlying technology reduces the cost, increases the precision and lowers the detectability of kinetic force.

Where this leads

The MIT demonstration represents a clear technical advance: insect‑level agility in an engineered platform that tolerates real‑world disturbances. The benefits for search‑and‑rescue, environmental sensing and inspection are genuine and significant. At the same time, the same capabilities — small size, maneuverability, autonomy — are precisely those that convert a scouting device into a stealthy delivery mechanism for harm.

What follows is largely a matter of governance: who controls the development pathway, how funding lines are conditioned, and whether international law and export controls can keep pace with rapidly shrinking hardware. The engineering problem is being solved; the societal problem is whether democratic institutions, funding agencies and the research community will write rules for the inevitable deployment, or simply watch the norms be set by earliest adopters.

Sources

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (research/press release on aerial microrobots)

- Office of Naval Research (funding statements and program summaries)

- Air Force Office of Scientific Research (funding statements and program summaries)

- Carnegie Mellon University (expert commentary on microrobotics)

- CIA Archives (historical Insectothopter projects and related documentation)

- MIT Lincoln Laboratory (institutional research context)