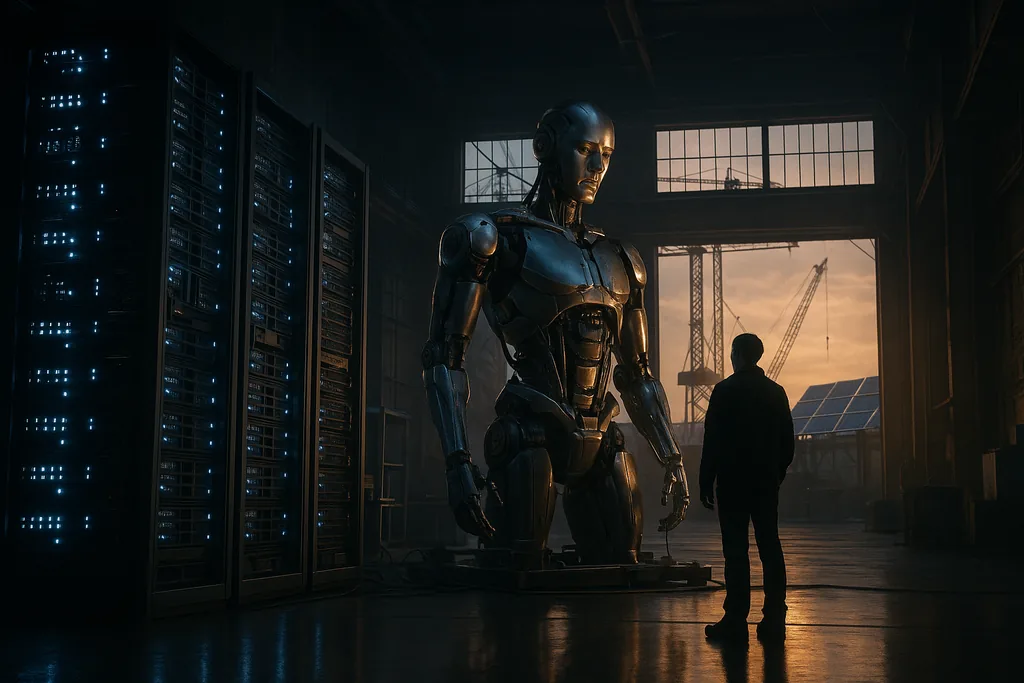

A declaration at Giga Texas

On a cold December evening inside Tesla’s vast Gigafactory in Austin, Elon Musk told Peter H. Diamandis and a small audience that the way we usually imagine the "technological singularity"—a single future date when machines suddenly outstrip human intelligence—misses the point. "We are already in the singularity," he said, framing the present as a process rather than a moment. The long conversation, recorded on December 22, 2025 and published as a Moonshots podcast episode in early January 2026, laid out a tightly compressed vision: artificial general intelligence (AGI) could appear within a year, robots will extend AI into the physical world, and the short term will be chaotic even as a far richer abundance becomes technically possible.

Timelines, metaphors and the "supersonic tsunami"

Musk used blunt metaphors. He called the convergence of AI and robotics a "supersonic tsunami"—an inexorable, high‑speed force that builds quietly and then hits with overwhelming momentum. In his telling, AGI is not a single breakthrough but the compounding effect of algorithmic gains, richer data, cheaper compute and new electromechanical platforms. He said AGI could plausibly emerge in 2026 and that by about 2030 AI systems might collectively exceed the cognitive capacity of all humans. Those are aggressive timelines that compress widely debated roadmaps into a handful of years.

That compression matters because it reframes policy, business and labour choices as urgent. If AGI and highly capable, general‑purpose robots arrive in a two‑to‑five‑year window, regulators and companies will have only a brief period to adapt governance, safety testing and workforce transition plans before automation accelerates. Musk explicitly warned that the transition will be "very bumpy"—three to seven years of simultaneous prosperity and social unrest.

Optimus, surgeons and the physical frontier

Musk’s argument is not limited to language models or cloud software. He framed Tesla’s Optimus humanoid program as the mechanism that will carry AI into physical labour at scale. Optimus, he suggested, will combine three accelerating curves—software intelligence, chip and compute density, and electromechanical dexterity—to produce rapid improvements. He forecasted that humanoid robots could match or surpass human surgeons within a few years because every robot can instantly share the combined experience of every prior operation. That claim underlines a key difference from past waves of automation: robots could replace bodily skills as well as cognitive tasks.

Alongside robotics, Musk returned to a recurring theme: energy is the hidden bottleneck. He argued that power and cooling—not chips—are becoming the gating constraint for massive AI fleets, and that whoever solves large‑scale, cheap power will dominate compute capacity. That is why he reintroduced space and Starship into the same sentence: if launch costs fall enough, orbital data centers and space‑based solar collectors become plausible long‑term infrastructure for planet‑scale AI.

From Universal Basic Income to "Universal High Income"

On the economic side Musk sketched a future in which the marginal cost of most goods falls toward the price of materials plus electricity, making scarcity less central. He suggested the old policy term "Universal Basic Income" understates what may be needed and floated a concept he calls "Universal High Income"—a redistribution that responds to extreme abundance rather than merely a floor under wages. He acknowledged the paradox: abundance can coexist with political instability, because work provides identity and structure as well as income. Without clear institutions and social design, the transition could be destabilising even as material conditions improve.

Why experts caution against a single‑point singularity

Not everyone accepts Musk’s timetable or framing. Some researchers model AI progress as a superposition of multiple logistic growth waves, finding that current deep‑learning methods show rapid gains but may face diminishing returns without fundamental innovations. An academic preprint that analysed historical AI growth suggests that 2024 marked the fastest point of a wave and that, absent new paradigms, current approaches could plateau in the 2035–2040 window. Those analyses argue the "singularity" is a contested concept: it may be a process with many local peaks rather than a single, predictable explosion.

That debate matters because it changes where attention should go. If singularity‑style discontinuities are plausible in the immediate future, the priority is near‑term containment, robust testing and international coordination. If progress is likely to be slower or to stall, policy can focus more on long‑range structural adjustments—education, social safety nets and climate‑resilient infrastructure—without the same sense of extreme time pressure. The evidence right now does not settle the question; it only sharpens the policy stakes.

Industry lever arms: compute, chips and supply chains

Musk repeatedly emphasised that energy and electricity generation—plus supply chains for metal and rare materials—will determine how quickly robot fleets scale. He singled out China as a likely frontrunner for raw compute capacity because of its ability to add gigawatts of power quickly; several news outlets summarised Musk’s view that China could significantly outpace others in AI compute due to power scaling. That view has immediate implications for industrial policy: export controls on chips matter, but so does domestic power infrastructure, grid storage and manufacturing of the mechanical components that robots require.

Policy, safety and the human margin

Musk briefly offered three moral pillars he believes ought to guide AI development—truth, curiosity and beauty—arguing these intellectual habits keep systems aligned with human values. Whatever one thinks of that formulation, his broader point was institutional: the speed of commercial incentives threatens to outpace regulators. If companies can translate smarter models directly into lower costs and higher margins, market forces will push rapid deployment. That dynamic is already visible in software; robotics would extend it into deserts of physical labour, hospitals and construction sites. Governments, he warned, must act quickly to avoid runaway social dislocation.

A contested future, and what to watch

Musk’s Giga Texas declaration is notable because it packages familiar predictions—AGI timelines, robotisation, space infrastructures—into a concentrated near‑term horizon. For engineers and policy makers, the immediate watchlist includes five measurable items: the public safety testing of large AI models, the demonstrable dexterity and autonomy of Optimus prototypes in unstructured tasks, national grid and battery deployments that materially expand dispatchable power, launch‑cost milestones for Starship and similar heavy‑lift rockets, and peer‑reviewed evidence that AI systems can safely generalise across domains without human oversight. Progress—or failure—on any of those fronts in 2026–2028 will make Musk’s scenario easier or harder to square with reality.

For readers who follow space, chips and the industrial supply chains that make robots possible, the conversation in Austin matters because it ties those threads together: robots do not scale on software alone, and superintelligent systems will be as much a question of kilowatts and metal as of math. Whether one accepts Musk’s confidence or treats it as one influential scenario among many, the practical consequence is the same—action and contingency planning are overdue.

Sources

- Moonshots with Peter Diamandis (podcast episode featuring Elon Musk, recorded December 22, 2025)

- Tesla — statements and technical briefings related to Gigafactory Austin and Optimus development

- SpaceX — Starship and orbital launch capability briefings

- arXiv (preprint): "Will the Technological Singularity Come Soon?" (multi‑logistic growth model, Feb 2025)

- arXiv (preprint): "The Butterfly Effect of Technology" (Feb 2025)