Musk’s Post‑Work Prediction: How Real Is a Jobless Future?

Elon Musk’s claim, in one line

At a high‑profile business forum in Washington this month, Elon Musk predicted that "work will be optional" within roughly 10 to 20 years and suggested that continued advances in artificial intelligence and robotics could eventually make money "irrelevant." The remark drew applause and immediate headlines because it collapses two big questions—the technical possibility of automating most human labour, and the political choice of how to distribute any gains—into a single, sweeping forecast.

He’s said this before

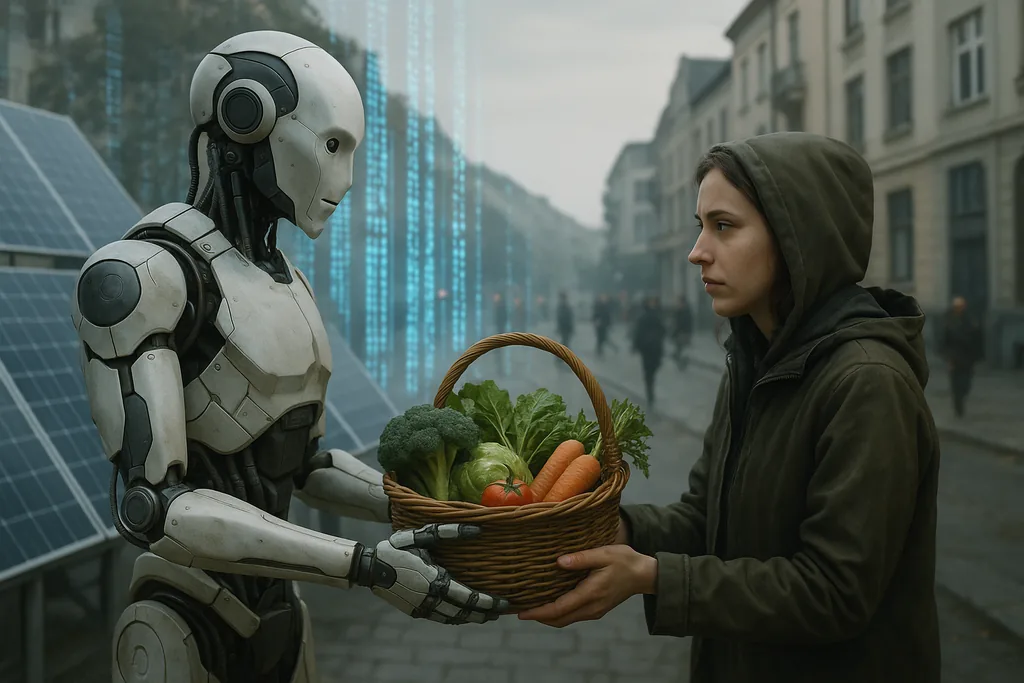

This optimistic post‑work narrative isn’t new for Musk. Over recent years he has repeatedly floated the idea of a future in which advanced AI and fleets of humanoid robots deliver such abundance that societies could support something beyond modest safety‑net payments—what he has called "universal high income." He’s framed the main remaining challenge as psychological: if machines can supply everything people need, how will individuals find meaning? That recurring theme helps explain why his comments keep landing in popular conversation.

What would need to happen — technically

Musk points to two technical building blocks: much stronger AI and humanoid robots that can operate safely and cheaply in human environments. Tesla’s humanoid project, Optimus, has shown incremental progress in public demos—improvements in walking gait, basic arm and hand coordination, and some delicate manipulation in curated settings are real engineering milestones. But the robots shown so far are prototypes operating in controlled conditions; moving from those demos to reliable, inexpensive machines that can replace a wide range of human tasks is a massive leap in hardware, power management, perception, and robust real‑world learning. In short: noticeable progress exists, but the distance from controlled demos to general, low‑cost deployment remains large.

And economically — it’s not just about robots

Even if humanoid robots and AI agents become technically capable, whether they eliminate the need for work depends on how the gains from automation are distributed. Economists note that automation creates both displacement and productivity effects: machines can remove tasks humans do today, but productivity gains can also generate new demand, new roles and higher incomes for some workers. Empirical reviews and policy agencies emphasise that the net effect is ambiguous and varies by country, industry and the design of institutions—education, taxation and social safety nets matter a great deal. That ambiguity undercuts any simple timetable for society‑wide joblessness.

Policy recipes Musk mentions — and how they’ve fared

Musk and other tech leaders have pointed to big cash transfers—universal basic income or his preferred phrase, "universal high income"—as a mechanism to share the abundance. Policy experiments to date give a mixed picture. Large pilots show clear improvements in recipients’ wellbeing and financial security, and some small pilots reported modest employment gains for targeted populations. But formal trials also reveal design challenges: small sample sizes, limited scope, political limits on funding, and differences between short‑term pilots and long‑run national programs. These experiments suggest cash transfers can soften transition costs, but they do not by themselves deliver the political settlement needed to make a post‑work economy viable.

Why timing matters — and why forecasts go wrong

Bold timeframes are familiar in tech: turning a prototype into a mass, affordable product often takes far longer than initial demos imply. Robotics faces particular friction: physical machinery must contend with energy density limits, wear and tear, and an open, messy world where edge cases are common. Musk acknowledged remaining constraints—power and mass among them—when sketching a long view, and added that the path to abundance will still involve "a lot of work" to reach. Put bluntly: predicting a societal shift within a single decade or two risks underestimating both engineering hurdles and slow-moving economic and political adaptation.

Who gets the gains matters more than whether gains exist

One sharp critique of Musk’s argument is political rather than technical: automation historically tends to concentrate gains in the hands of capital owners unless deliberate redistribution occurs. If firms capture most of the productivity lift, automation can deepen inequality rather than erase work necessity. That’s the core of the political problem: machines could produce abundance, but absent strong policy choices—tax reform, social insurance, public investment, new labour institutions—that abundance won’t automatically translate into universal security. Musk’s vision presumes redistribution will follow technological advance; experience shows that outcome is not automatic.

Short‑term effects to expect

- Task shifts rather than wholesale elimination: many occupations will be reconfigured as AI takes on repetitive, routine or information‑heavy tasks. That creates demand for complementary skills such as oversight, creativity and social judgement.

- Uneven regional and sectoral impacts: automation will hit some regions and low‑skilled roles harder, while creating new opportunities in tech, care, and creative sectors.

- Political pressure for safety nets and reskilling: the concentration of gains will likely increase calls for stronger redistribution, retraining programs, and local pilot guaranteed‑income schemes.

What to watch next

Three things will make Musk’s broader claim more or less plausible: first, whether humanoid robots move from curated demos to sustained, low‑cost service roles outside lab conditions; second, whether AI systems continue to generalise across domains rather than excel only at narrowly defined tasks; and third, how governments and firms decide to share productivity gains—through taxation, public goods, or private accumulation. Technical progress alone won’t make work optional for large numbers of people; the societal bargain about who receives economic surplus will.

Bottom line

Elon Musk’s headline—work will be optional in 10–20 years—captures an influential techno‑utopian possibility. It is a useful provocation: it forces policymakers to ask how to design institutions for widespread automation. But the claim bundles hard engineering problems and even harder political choices. The plausible near‑term future is one of powerful, uneven technological change: more automation, more productivity, mixed job disruption, and a heated debate about redistribution. Whether that evolves into a painless, post‑work abundance depends less on a single company or CEO than on public decisions about tax, labour policy, welfare design and democratic control of new technologies.

— Mattias Risberg, Dark Matter. Based in Cologne, reporting on robotics, AI and the policy choices that will shape how technology changes work.