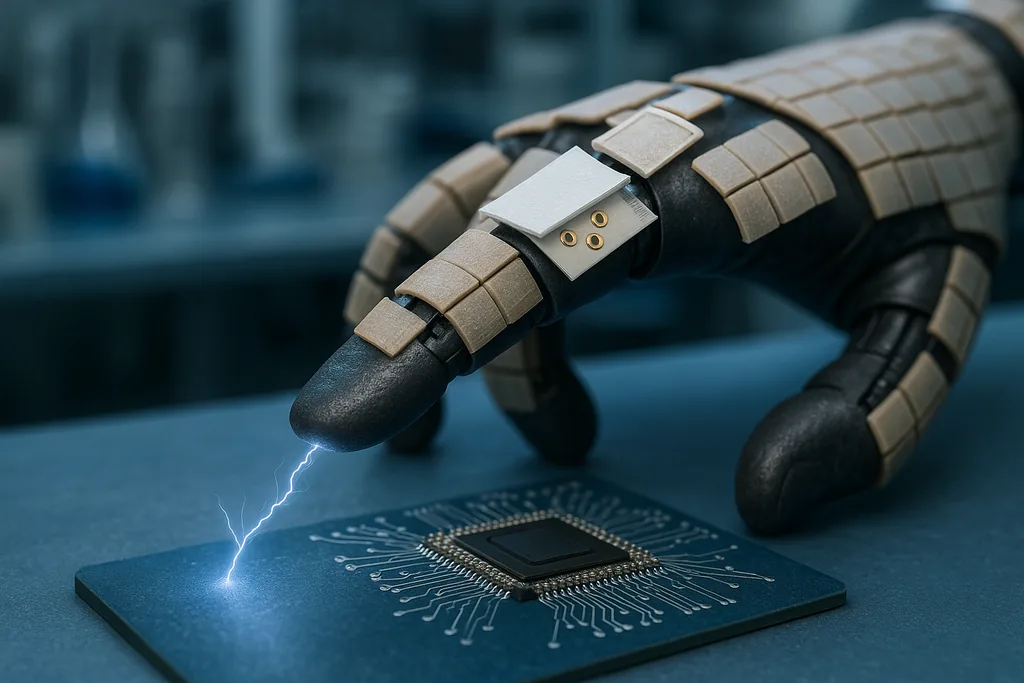

Today, a major step toward sensory robots arrived in the lab

In a lab demonstration this week, engineers showed a flexible artificial covering for robotic limbs that doesn't merely measure pressure — it encodes touch into electrical spikes much the way peripheral nerves do. The system, developed by a team of researchers in China and described in media briefings today, converts squeeze and pressure into short bursts of voltage that carry both intensity and location information. Embedded diagnostics, magnetic snap-on modules and a built‑in "pain" threshold mean the skin can detect damage and trigger reflexes without waking a central processor.

How the new skin speaks like a nervous system

The core idea is deceptively simple: biological touch uses bursts of electrical activity — spikes — to carry tactile data. The new synthetic covering replicates that mode of communication rather than shoehorning biological-style signals into traditional continuous sensor streams. Each patch of the material houses pressure-sensitive elements wired into conductive polymers. When a point on the skin is pressed, that sensor emits a packeted electrical pulse. Rather than using a single number for force, the pulses vary across four parameters — shape, magnitude, duration and frequency — creating a compact, spike-based barcode that identifies both how hard the robot was touched and where.

That local encoding makes two practical things possible. First, the skin can run elementary processing at the edge: patterns that exceed a programmed threshold produce a reflexive response, such as retracting a manipulator. Second, each tile broadcasts a regular status heartbeat; if it stops, higher-level controllers know a component has failed and can map the fault to a particular module.

Complementary breakthroughs in tactile fabrics and sensors

This Chinese prototype isn't the only team pushing robots toward human-like touch this year. Earlier in 2025, researchers at the University at Buffalo published work in a top journal showing an electronic textile that senses not only pressure but also slip. Their sensor relies on the tribovoltaic effect: tiny relative movements between layers create direct-current signals fast enough to detect micro-slips. Embedded on 3D‑printed robotic fingers, that fabric can detect an object beginning to slide and close the grip in a fraction of a millisecond — response times comparable to human mechanoreceptors.

Material scientists have also been exploring multi-modal artificial skins that respond to temperature and humidity as well as force. Teams working with engineered nanostructures and piezoelectric layers have shown that tiny, hair‑like cylinders can transduce touch, heat and moisture into electrical signals. The result is a roadmap of sensor types that, if combined, could approximate the rich palette of natural skin.

Why a spiking approach changes the engineering trade-offs

Most industrial sensors stream tidy analog or digital values to a central controller. That model is simple to design but costly in energy and bandwidth when a machine needs to continuously monitor hundreds or thousands of contact points. Spiking signals are sparse and event-driven, which plays to the strengths of a different class of processors: neuromorphic chips built to handle spikes natively. By encoding contact as bursts, the skin can hand pre‑processed, low-dimensional tactile cues to energy-efficient spiking networks, reducing latency and power consumption — critical for battery‑powered robots and prosthetics.

Engineers point out that the new approach is bio‑inspired rather than biologically identical. Human nerves keep positional maps in the architecture of the nervous system; the brain recognizes which neurons fired. The robotic skin instead encodes location into the pulse itself — an engineering shortcut that is easier to manufacture but has different implications for scalability and learning.

Practical design choices: modularity, repair and reflexes

One striking practical touch in the prototype is modularity. The skin is built from magnetically coupling tiles that jointly carry power and signals. Each tile transmits a unique ID; if the system detects a broken heartbeat signal, an operator can swap in a replacement and the control software remaps the skin automatically. That maintenance‑friendly layout acknowledges an important industrial reality: laboratory skins are fragile. Making them easy to service and replace shortens the path from prototype to factory floor.

The researchers also programmed a "pain" response calibrated to human sensitivity benchmarks. When summed activity at a location passes the threshold, the local controller triggers an immediate withdrawal. That kind of embedded reflex is deliberately conservative — it keeps the robot from crushing objects or injuring nearby humans — and it lightens the real‑time burden on central CPUs.

Where this matters first

- Prosthetics: Adding low-latency touch and slip detection would let artificial hands adjust grip force without explicit user commands, making everyday tasks more natural.

- Medical tools and teleoperation: Haptic feedback that closely matches human timing and intensity helps surgeons learn and perform delicate tasks remotely.

- Consumer and companion robots: Soft, responsive coverings can make social robots feel safer and more believable — and raise complex social questions about emotional touch.

Technical and ethical hurdles ahead

Despite the promise, the new skins are partial. The Chinese prototype senses pressure only. Adding temperature, vibration and chemical cues without creating crosstalk will require parallel channels and clever multiplexing schemes. Manufacturing remains a bottleneck: depositing delicate, nanoscale piezoelectric structures or integrating conductive polymers across square metres at industrial cost is nontrivial.

Durability and contamination are real concerns. Real skin self‑repairs; artificial skins must be robust to abrasion, sweat, dust and cleaning regimes typical of industrial or medical use. Power delivery and secure connector standards will matter as tiles proliferate across a robot's body.

There are also social considerations. Touch carries emotional meaning. Haptics researchers have shown that machines that respond to touch can evoke comfort and attachment — a feature that developers and regulators should treat deliberately, not accidentally. Engineers will have to balance usefulness and safety without normalizing artificial touch as a substitute for human contact in contexts where it would be harmful.

Next steps and the path to deployment

Integration with neuromorphic processors and spiking neural networks is the logical next step: the skin's event-driven output is a natural fit for hardware optimized for spikes. Teams will also combine different sensing modalities into layered skins and test them in real‑world scenarios: assembly lines, rehabilitation clinics and surgical training suites. Because the modular design anticipates maintenance, early adoption is likeliest in settings where uptime and safety are paramount rather than in consumer gadgets.

Taken together, the recent demonstrations map a convergent trend: materials that feel, encoding schemes that mimic nerve signaling, and processors that natively handle spikes. That stack addresses a long-standing gap between human dexterity and robotic manipulation. It does not give robots a mind; it gives them a faster, leaner way to feel the world and act on that feeling.

Those developments will not erase the remaining technical work — each additional sense adds architectural complexity — but they do mean that robots and prosthetics will soon feel touch in ways that matter for performance, safety and human interaction.