Scientists Grow First Fully Synthetic Brain Tissue

UC Riverside team builds a brain‑like tissue without animal-derived ingredients

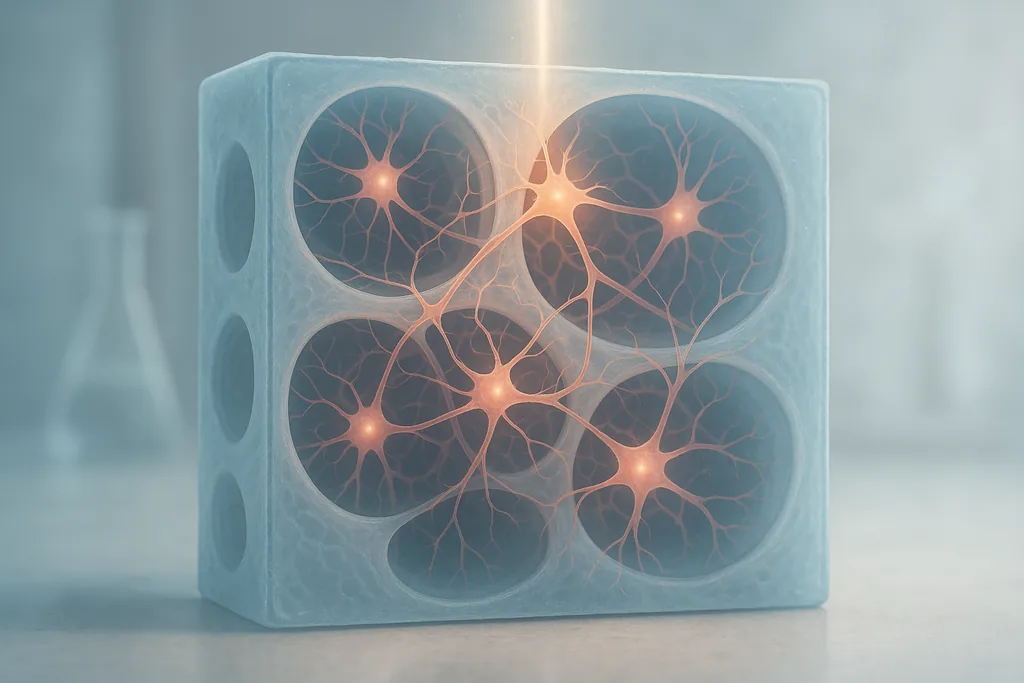

In a development that could reshape how labs study the brain, researchers at the University of California, Riverside report they have grown functioning, brain‑like tissue on a scaffold made entirely from synthetic materials. The work replaces commonly used animal‑derived coatings and extracellular matrix extracts with a chemically neutral polymer whose physical architecture alone guides human donor cells to form neural networks. This approach aims to make neurological testing more controllable, longer lived, and less dependent on animal models.

How the scaffold is made

The team built their scaffold from polyethylene glycol (PEG), a widely used, biocompatible polymer that is normally inert to cell attachment. Instead of adding biological ligands such as laminin or fibrin — standard supplements that are often sourced from animal tissues — the researchers reshaped PEG into a highly textured, interconnected porous maze. Cells seeded into the pores are able to access oxygen and nutrients and, crucially, organize into brain‑like clusters that communicate electrically once mature.

To make that porous microarchitecture the group used a flow‑based manufacturing step: solutions of water, ethanol and PEG were pumped through nested glass capillaries so that the mixture phase‑separated on contact with an outer water stream. A burst of light then fixed the separated structure in place, producing a stable, highly porous scaffold that can be seeded with donor neural cells. That controlled physical structure is what the researchers say the cells respond to, rather than biological coatings.

Why the synthetic route matters

Most current three‑dimensional neural culture platforms rely on biological extracts — for example, basement membrane preparations — that are chemically complex, variable between batches, and often derived from animal sources. Those variables make experiments harder to reproduce and complicate efforts to translate findings into human medicine. By contrast, PEG is chemically well defined and non‑immunogenic, so scaffolds built from it can be manufactured with consistent composition and mechanical properties, and do not require animal‑derived supplements to support cell growth when microarchitecture is optimised properly. These material properties have made PEG hydrogels a foundational tool in neural tissue engineering for years; the new work demonstrates a route to make PEG not just permissive but instructive for neural organisation by tailoring its internal geometry.

Where this fits with other brain models

Over the past few years labs have pushed organoid and assembloid technologies — self‑assembled clusters of human stem‑cell‑derived neurons that can model aspects of brain regions and pathways — to remarkable fidelity, including reproducing circuits that transmit sensory signals. Those systems rely on the biochemical cues and cell‑self‑organization provided by biological matrices and complex protocols. The UC Riverside scaffold is complementary: rather than relying on biological complexity, it offers a physically defined platform that may improve reproducibility and longevity for experiments that need stable, donor‑specific networks. Together, these approaches give researchers different trade‑offs between biological realism, experimental control, and ethical concerns about animal use.

Potential applications and advantages

The researchers highlight several near‑term uses: modelling traumatic brain injury and stroke mechanics, studying disease processes such as Alzheimer’s in donor‑specific cells, and screening neuroactive drugs without animal tissue. Because the synthetic scaffold is stationary and less prone to biochemical degradation, it can support longer experiments that allow neural cells to mature — a key requirement since many features of neurological disease emerge only in mature neurons. The team also sees this as a first step toward assembling networks of different organ models so scientists can study interactions between the brain and other tissues in a controlled way.

Limits and the path to scale

The current scaffolds are small — roughly two millimetres in width — and the researchers acknowledge several engineering challenges before the approach can replace larger or more complex models. Chief among them is perfusion: larger tissue constructs need integrated vasculature or efficient synthetic channels to deliver oxygen and remove waste. Designing and manufacturing vascular networks that can sustain organ‑scale tissues, and connecting those networks to the synthetic brain matrix, remain active areas of research. There are also questions about how immune interactions, blood–brain barrier physiology, and other systemic influences can be modelled in an entirely synthetic scaffold.

Ethics, regulation and the promise of fewer animals

Aside from experimental reproducibility, the synthetic scaffold addresses ethical and regulatory pressures to reduce animal testing. Regulatory agencies and funders in several jurisdictions are encouraging development of non‑animal test systems for drug safety and efficacy, and defined synthetic platforms could accelerate that transition by offering repeatable, human‑relevant test beds. Still, regulators will expect careful validation showing that responses in the synthetic model predict outcomes in humans, and that will take time and cross‑laboratory replication.

What to watch next

- Scaling — demonstrations of larger constructs and integrated synthetic vasculature or perfusion systems.

- Functional validation — electrophysiology and drug‑response studies that show predictable, donor‑specific behaviour relevant to disease.

- Cross‑platform comparisons — head‑to‑head tests comparing synthetic scaffolds, organoids, and animal models for the same drug or insult.

- Regulatory engagement — early conversations with agencies to define how synthetic tissues could be used in preclinical pipelines.

The UC Riverside team began the project in 2020 and has funding support from internal startup funds and state regenerative medicine grants. The scaffold concept has already led the group to submit related work on synthetic liver tissue and they continue to pursue strategies to connect organ‑level cultures into interacting systems. If those next steps succeed, the approach could provide researchers with a new class of human‑centric, scalable tissue models for neuroscience and drug discovery.

James Lawson is an investigative science and technology reporter for Dark Matter. He holds an MSc in Science Communication and a BSc in Physics from University College London, and covers advances across AI, space, and quantum technologies.