A physics paper brings warp drive back into serious discussion

This week a group associated with the Applied Physics public benefit company published a paper describing what they call a "physical" warp drive: a mathematical and geometrical model of a warped spacetime bubble that can be written down using only ordinary, well‑understood ingredients of general relativity. The announcement has rippled across the community because it directly addresses the single largest objection to the most famous warp metric: the Alcubierre drive’s reliance on large quantities of so‑called negative energy. That requirement has long been treated as a showstopper because negative mass and large volumes of negative energy are not things we know how to create or handle in the laboratory.

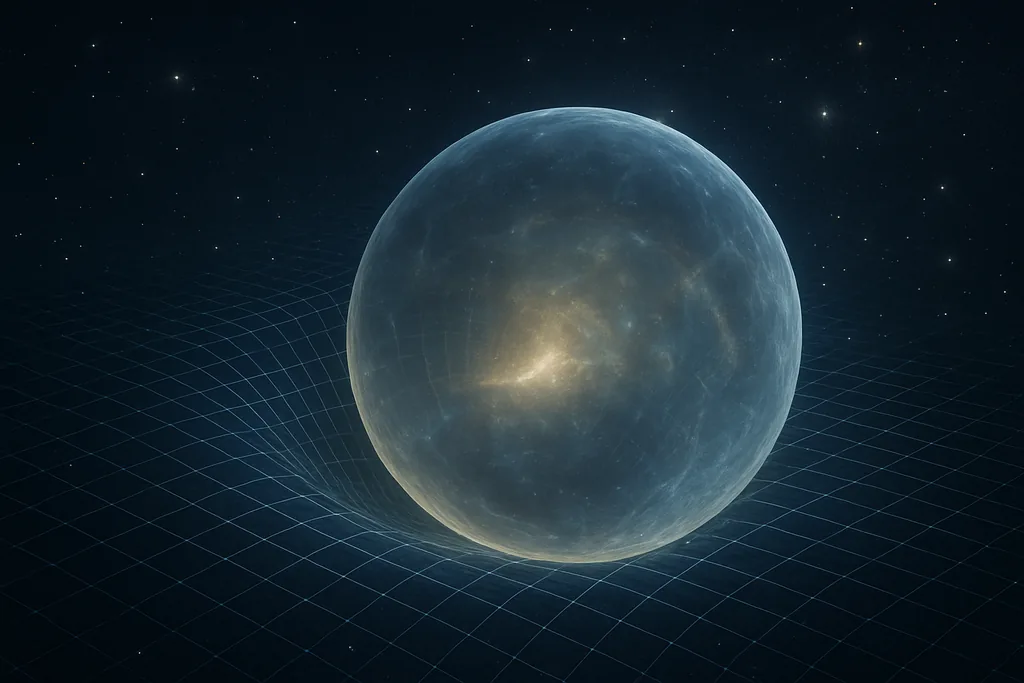

Popular coverage of the work has framed it as a step from mathematical fantasy toward engineering plausibility; researchers in the field are quicker to qualify the advance. The new model reframes the problem, replacing the exotic‑matter Alcubierre bubble with a different spacetime geometry — a constructed bubble whose physics can, at least on paper, be described using normal energy and mass distributions. Crucially, the team behind the paper emphasize that the model is a theoretical design, not a prototype, and that the mass–energy budgets it implies today are still enormous.

A physical model for a warp bubble

That shift — from a metric that is mathematically viable but physically suspect, to a metric that is constructed from physically allowed stress–energy profiles — is why some researchers call the paper a milestone. It gives theorists a concrete target: if you want to understand whether a warp bubble can exist, here is a geometry you can analyze with standard tools of numerical relativity and field theory.

Lineage: from Alcubierre to current research

Work on warp metrics has not been continuous mythmaking; it has been a running research programme that repeatedly sought to push the original idea into physical territory. Over the past three decades a stream of papers explored optimizations and alternatives: shrinking the required exotic energy with clever topologies, altering bubble thickness and ring geometries, and looking for subluminal variants that operate without violating energy conditions. Some efforts, including experiments and engineering studies inside NASA’s Eagleworks and proposals from independent institutes, focused on how to reduce the raw numbers behind the energy requirement.

Engineering and energy scales

To put it bluntly: reducing a theoretical dependence on exotic negative energy does not automatically make a system buildable. The remaining positives are still enormous. Estimates in follow‑on commentary and related papers give required masses on the order of planets or at least giant planetary masses for meter‑scale bubbles, far beyond any conceivable engineering program today. Other researchers are therefore pursuing a pragmatic, incremental strategy: design subluminal or near‑relativistic warp configurations that satisfy the standard energy conditions and then optimize how the bubble is shaped, how its wall is constructed, and how it could be created using dense, controllable mass–energy distributions.

Those intermediate goals matter. Several groups have published subluminal warp metrics that satisfy the four standard energy conditions, and one practical aim now is to find metrics whose resource requirements could, in principle, be reached by advanced future technologies or by clever use of local energy reservoirs.

Searches, tests and possible signatures

One striking implication of reframing warp bubbles as physical objects is that they should have observable footprints. A collapsing or otherwise disturbed bubble would generate gravitational waves; in 2024 a team modelled the gravitational‑wave signature of a warp‑bubble collapse and argued that, if a breach happened within a few million light‑years, it would create a measurable signal — albeit at frequencies far higher than LIGO’s current sensitivity band. That idea recasts warp drives from purely speculative engineering into something astrophysicists could conceivably search for: a high‑frequency gravitational signature not produced by ordinary astrophysical collisions.

Caution and the long view

Researchers across the spectrum — from those who love the romance of Star Trek to sober relativists — urge caution. The theoretical advance is real: a model that removes an obvious impossibility from an earlier proposal is important. But the gulf between a theoretically allowed geometry and a practical propulsion device is vast. The current consensus among working physicists is that a realistic timetable is measured in decades to centuries, not months or a handful of years.

That said, this is the kind of problem that prompts useful cross‑disciplinary work. Numerical relativists, gravitational‑wave experimentalists, materials scientists, and energy systems engineers can all contribute to the cascade of partial results that could make future progress possible. Whether or not humans will ever ride a warp bubble, the research pushes the tools and questions of gravitation theory, computational physics, and detector design in directions that produce scientific returns well before any starship appears.

For now, the headline is precise: a physically coherent model for a warp bubble exists on paper, and it no longer needs the exotic, negative energy that made earlier proposals seem impossible. Turning that model into a technology remains a monumental challenge — but not an illogical one, and that change in status is why this paper has reignited attention and sober ambition in the field.

Sources

- Classical and Quantum Gravity (research paper on physical warp drives)

- Applied Physics (Applied Physics public benefit company)

- Monash University (Alexey Bobrick, theoretical work on warp metrics)

- NASA Eagleworks Laboratories (warp‑drive studies and Warp Field Mechanics)

- University of Alabama in Huntsville (Jared Fuchs and collaborators on warp metrics)

- LIGO Scientific Collaboration (gravitational‑wave detection and related simulations)