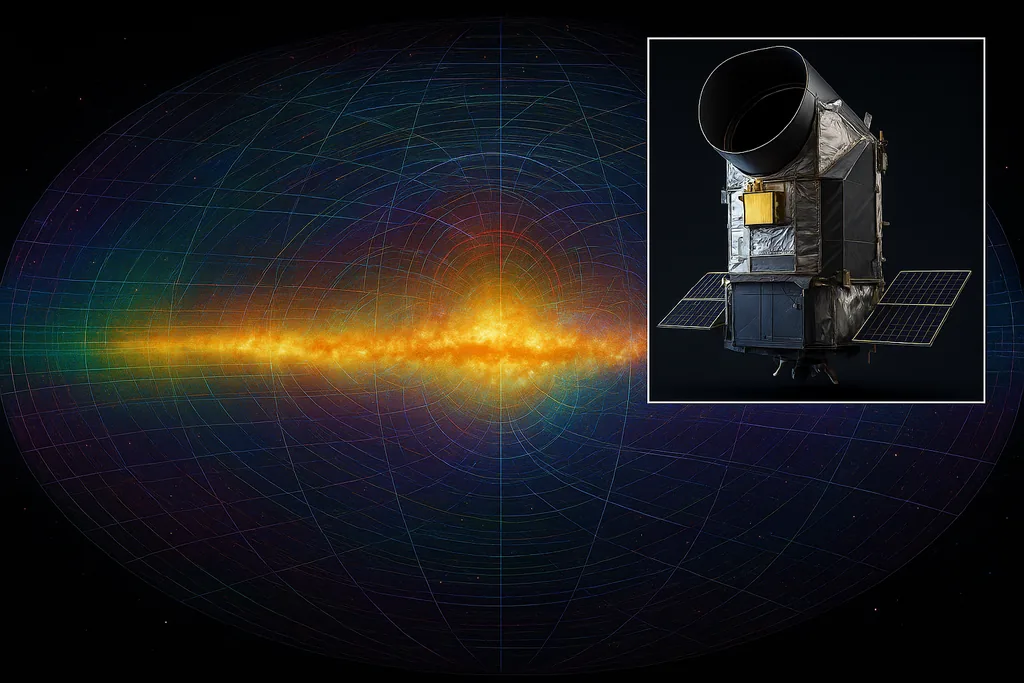

On 19 December 2025 NASA announced that its new space observatory SPHEREx has finished a striking first milestone: an all-sky survey captured in 102 distinct infrared wavelengths. In just six months of science operations the mission produced not one picture but a vast stack of overlapping maps — each wavelength revealing different physical and chemical features across the sky, from the dusty lanes of our galaxy to the faint glow of distant galaxies whose positions carry information about the universe’s earliest instant of expansion.

A telescope of many colors

SPHEREx — the Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer — was designed to do something unusual for a space telescope: combine wide coverage with moderate spectral resolution. Instead of a handful of broad filters or one high-resolution spectrograph pointed at a tiny patch of sky, SPHEREx uses six detectors and a set of narrow-band filters so that each exposure records 102 separate wavelength measurements. That technical choice turns every image into a 102-channel data cube, letting astronomers see how different materials and temperatures glow in the infrared.

Those infrared wavelengths are invisible to the eye but crucial for modern astronomy. Cold dust, molecular ices, and faint star-forming regions are bright in the infrared even when optical telescopes see nothing. As SPHEREx circles Earth roughly 14.5 times per day, scanning daily strips of sky and letting the orbit geometry shift its viewing strip as Earth moves around the Sun, it built up coverage of the entire celestial sphere over half a year. Mission scientists have compared the observatory’s multicolor capability to the mantis shrimp’s hyper-spectral vision — a compact way to convey how much more information SPHEREx captures at once.

From flat sky to a three‑dimensional atlas

One of the mission’s most consequential functions is turning a two-dimensional sky map into a three-dimensional atlas of the nearby and distant universe. Light from distant galaxies is stretched to longer wavelengths by cosmic expansion — the familiar phenomenon called redshift. Measuring how a galaxy’s light shifts across many narrow wavelength bands gives an estimate of its distance. SPHEREx’s 102 measurements per source provide far more spectral detail than ordinary broad-band imaging, so photometric redshifts become much more precise for hundreds of millions of galaxies.

That depth is not academic: the pattern of how galaxies cluster in three dimensions traces the web-like scaffolding that dark matter laid down and encodes tiny variations that were imprinted when the universe inflated in the first fractions of a second. Cosmologists hope SPHEREx will help test whether the simple inflation models are correct, and whether those primordial quantum fluctuations really seeded the galaxies we see today. Put simply, SPHEREx does the cosmic equivalent of measuring the fossilised ripples from the universe’s birth.

Mapping the Milky Way's frozen chemistry

SPHEREx is not only a cosmology instrument. One of its core goals is to inventory the inventory of ices across our galaxy. Water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide ices coat dust grains in cold molecular clouds and later become part of comets, planets and other small bodies. By detecting the characteristic spectral signatures of these molecules in the infrared, SPHEREx can locate concentrations of the raw materials for planets and potentially for life.

Because the mission surveys the whole sky every six months and plans several full-sky passes during its two‑year prime mission, it will build a dynamic picture of where ices are concentrated and how those reservoirs evolve. That systematic, galaxy-wide census is unique and will provide targets for follow-up by higher-resolution facilities that can zoom in to study particular clouds, young stellar systems or visiting interstellar objects.

Cosmology: getting at inflation’s fingerprints

Inflation — the hypothesised ultra-rapid expansion of space in the first 10^-32 seconds after the Big Bang — has been a successful explanatory framework, but it has remained largely theoretical because of the difficulty of connecting it to late-time observables. SPHEREx offers a practical way to close that gap by mapping the statistical distribution of galaxies across enormous volumes. Those statistics can reveal subtle features, such as departures from purely Gaussian distributions in the density field, that would point back to the physics of inflation.

SPHEREx will not provide a single definitive answer; rather, it will add a powerful new dataset to the toolbox of cosmologists. When combined with careful modelling, gravitational lensing surveys, and spectroscopic follow-ups, the mission’s photometric redshifts for hundreds of millions of galaxies can sharpen constraints on inflationary models and on the nature of the dark matter scaffolding that shapes galaxy formation.

How SPHEREx complements the observatory fleet

SPHEREx deliberately sits between two familiar observing strategies. Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope deliver extremely detailed spectra but only over tiny fields of view; all-sky missions such as WISE covered the entire sky but with far fewer colours. SPHEREx’s niche is to be a wide-field spectrophotometer: a sky scout that flags interesting objects, chemical fingerprints and three-dimensional structures for more focused instruments to study.

NASA and JPL emphasise that the mission’s data are meant to be a community resource. The full dataset has been released publicly, and the mission will perform at least three more full-sky passes during its prime operation to reduce noise and reveal fainter features. The result will be a growing, richly layered archive that researchers across astrophysics and planetary science can mine for discoveries the mission team did not anticipate.

Early results and future possibilities

Even in its first six months, SPHEREx has already produced striking false‑color panoramas that isolate emission from stars, hot hydrogen gas and cosmic dust. The observatory has observed objects inside our own Solar System — including interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS — and will be sensitive to transient phenomena such as supernovae and flaring stars. Those transient detections benefit from SPHEREx’s repeated all-sky cadence.

Over the coming years the mission’s layered maps should refine our picture of how galaxies assembled, where planet-forming ices live, and how the large-scale structure of the universe preserves an imprint of its earliest physics. The data will also guide expensive follow-ups with Webb and ground-based spectrographs: SPHEREx can point to the needles in the haystack that deserve the most intensive study.

Sources

- NASA (SPHEREx mission briefings and press materials)

- Jet Propulsion Laboratory (SPHEREx project office)

- California Institute of Technology (Caltech)