A serendipitous discovery on wounded skin

In a lab at the University of Sheffield, scientists studying wound healing noticed an unexpected side effect: skin treated with a simple sugar grew hair faster than untreated areas. That observation set a multi-year investigation in motion and culminated in a paper published in Frontiers in Pharmacology reporting that 2-deoxy-D-ribose (2dDR), a pentose sugar found naturally in cells, stimulated hair regrowth in mice whose follicles had been driven toward a balding state by testosterone. The authors say the sugar’s effect in this animal model was broadly comparable to the topical drug minoxidil, a standard treatment for pattern hair loss.

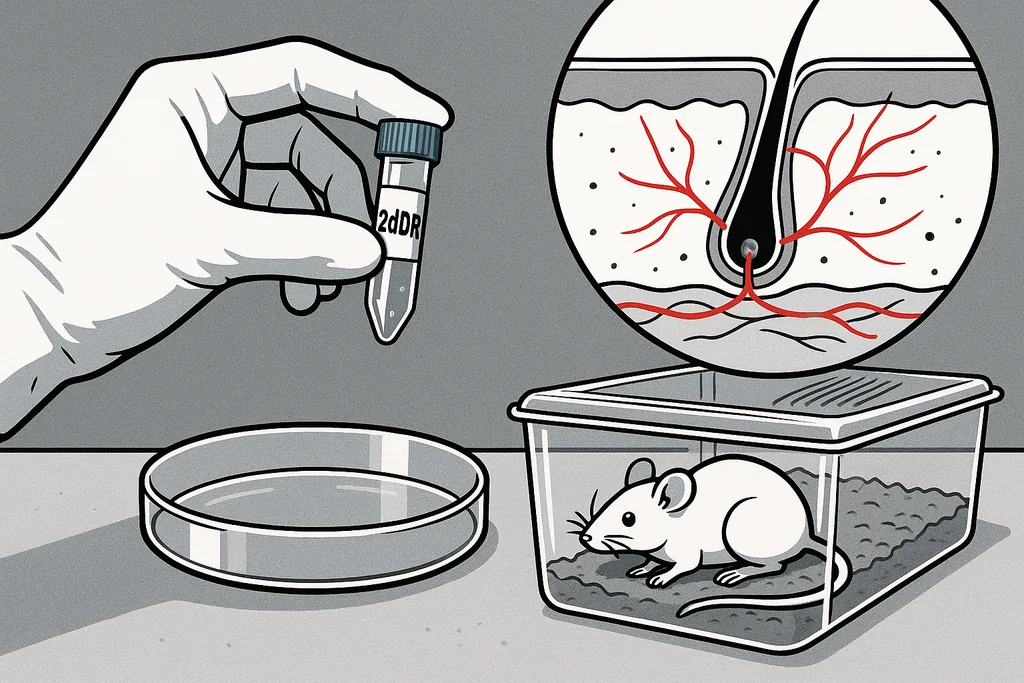

How the experiment worked

The team used C57BL/6 mice and a 20‑day topical treatment protocol. After creating a testosterone-driven model intended to mimic androgenic alopecia, they applied a hydrogel containing 2-deoxy-D-ribose to the dorsal skin and compared outcomes with untreated controls and with mice treated with minoxidil. The measures reported included hair length and thickness, hair follicle density, anagen/telogen ratio (the balance of growth versus resting follicles) and histology showing increased numbers of small blood vessels in treated skin. Across those endpoints, the 2dDR hydrogel produced an increase in hair growth metrics that the authors judged to be similar in magnitude to minoxidil in this mouse model.

What the mice actually showed — and why that matters

Early-stage evidence and scientific caveats

There are important limits to what the mouse results prove. Rodent and human hair biology differ: mouse pelage is patterned and cyclical in ways that do not map simply onto human scalp follicles, and many interventions that work in mice fail in human trials. The 2dDR study is preclinical and limited to a single species, a single lab protocol and a short treatment window; the authors explicitly describe the work as early-stage and call for mechanistic follow-up and safety testing before any human use. A corrigendum has also been published to correct figure and editorial errors in the original paper, and the authors state those corrections do not change the conclusions. Those adjustments are routine in scientific publishing but underscore the need to treat initial results with healthy scepticism.

Potential risks and unanswered safety questions

Because the paper links 2dDR’s effect to increased angiogenesis and possibly VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) signalling, safety questions naturally follow. Angiogenesis is fundamental to normal tissue repair, but it is also a hallmark of tumour growth: cancers exploit VEGF-mediated vessel growth to access nutrients and metastasise. That does not mean a topical angiogenic agent will cause cancer, but any therapy that stimulates blood vessel formation needs focused evaluation for off-target effects, dose dependence, duration of action and the behaviour of surrounding tissues—especially in people with a history of cancer or pre-cancerous lesions. Decades of oncology research demonstrate both the benefits and hazards of manipulating VEGF biology, so regulators and clinicians will expect careful preclinical toxicology and long-term monitoring.

Where this fits in the landscape of hair-regeneration research

Hair regrowth research splits into two broad strategies. One seeks to reactivate developmental or stem-cell programmes so new follicles are formed or dormant follicles reawaken; another improves the local niche around existing follicles—by changing blood supply, immune signals or extracellular matrix—to support growth. The 2dDR findings point to the latter: improving vascular support rather than creating new follicles from embryonic‑like programmes. Other recent studies have shown hair can be coaxed to regrow by mechanical stimulation, macrophage signalling, or wound-induced neogenesis in mice—different mechanisms that are all converging on the same clinical problem from distinct angles. That diversity is encouraging because it widens the therapeutic toolbox, but it also means any candidate therapy must be evaluated on mechanism, safety and human biology, not only on efficacy in rodents.

Commercial interest and the road to human testing

Within months of the study’s publicity, consumer product developers and start-ups flagged the science as a basis for topical formulations. Early-stage commercial efforts are framing 2dDR-based gels as cosmetic or cosmeceutical products in some markets, but those products are distinct from the clinical-grade formulations and regulatory studies required to prove efficacy and safety in humans. Translating a laboratory hydrogel into a product for people requires scaled manufacturing, stability and sterility testing, controlled clinical trials and regulatory review. Researchers and university press offices have emphasised that consumer hype should not outpace the science; the next logical steps are replicated preclinical studies, mechanistic work (for example, measuring VEGF levels directly and testing VEGF blockade) and Phase 1 safety studies in well‑characterised human volunteers.

Practical takeaways

- The 2-deoxy-D-ribose result is an intriguing, peer‑reviewed preclinical finding showing robust hair regrowth in a mouse model of testosterone-driven alopecia.

- Translation to humans is not assured; mouse hair biology is different, and the work remains at an early investigational stage with safety and mechanism unresolved.

- Because the putative mechanism involves angiogenesis and VEGF-related signalling, thorough testing for unintended effects—particularly any impact on tumour biology—will be essential.

- Commercial interest is already emerging, but prospective users should distinguish between early commercial formulations and therapies that have completed clinical trials.

For people living with hair loss the study offers a welcome note of possibility: a naturally occurring molecule, cheap and chemically simple, produced measurable hair regrowth in a controlled animal model. For scientists and clinicians it is a starting point—an observation that opens a pathway to deeper mechanistic work and careful translational testing rather than an immediate cure. The prudent next moves are replication, mechanistic dissection (for example, directly testing VEGF dependence), toxicology and phase‑1 human safety trials before anyone should consider routine use.

Sources

- Frontiers in Pharmacology (research paper: "Stimulation of hair regrowth in an animal model of androgenic alopecia using 2-deoxy-D-ribose").

- Frontiers in Pharmacology (corrigendum to the paper).

- University of Sheffield (research press materials and White Rose repository entries).

- Nature Communications (mechanical stretch hair‑regeneration study providing context on alternative regenerative mechanisms).

- PubMed / review literature on wound‑induced hair neogenesis (WIHN) and related regeneration models.