Tabletop Test for Quantum Gravity

Can a lab bench settle the deepest riddle in physics?

For a century physicists have been wrestling with an uncomfortable mismatch: quantum mechanics describes the micro-world with uncanny precision, while Einstein's general relativity governs the large-scale curvature of spacetime. The two frameworks work exceptionally well in their own domains, but they speak very different mathematical languages. That tension has driven searches for quantum gravity at particle colliders and in cosmology — until a recent idea suggested the question might be decided on a table-top experiment.

The core idea: entanglement as gravity’s fingerprint

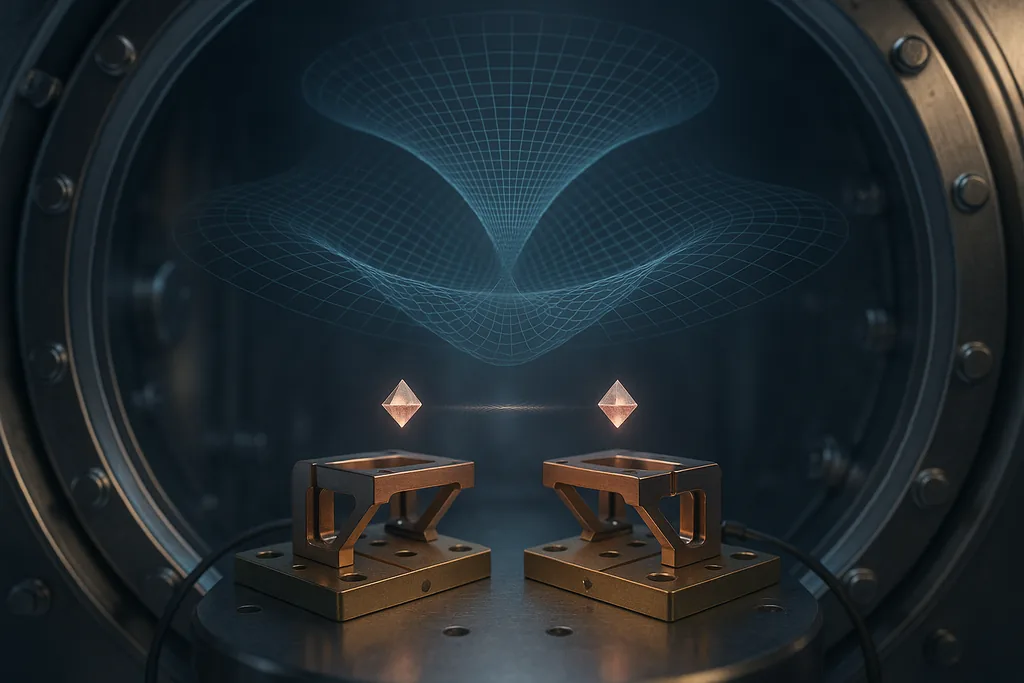

The proposed test is surprisingly simple in concept. Prepare two small masses in carefully controlled quantum states and let them interact only through gravity. If, after the interaction, the two masses become entangled — a uniquely quantum form of correlation — then the argument goes that the gravitational interaction must itself be able to carry quantum information. Two independent proposals from 2017 laid out protocols to do exactly that: one framed in terms of spins embedded in micron-scale crystals, the other in a more general information-theoretic language. Both show that, under experimentally plausible conditions, gravity could imprint a relative phase that is detectable as entanglement between the systems.

Why entanglement would be decisive — and why it’s not automatic

That logic is powerful, but it depends on assumptions. Critics point out that alternative, semiclassical models of gravity or carefully constructed non-local mechanisms can in some circumstances reproduce the same experimental signatures without introducing a quantized gravitational field. Other analyses have therefore urged caution: witnessing entanglement would be a major result, but interpreting it as a proof that the gravitational field is a standard quantum field requires careful control of assumptions and backgrounds. In response, theorists have sharpened the experimental prescriptions and the list of conditions that must be met for a clean inference.

How the experiment could be built

Practical proposals fall into a few technological families. One prominent approach uses levitated nanoparticles — tiny diamonds or silica beads that are trapped and cooled in vacuum and whose center-of-mass motion is prepared in spatial superpositions. Embedding a quantum spin (for example a nitrogen-vacancy center) in each crystal converts spatial superpositions into spin-dependent phases that can be read out as entanglement. Another strategy exploits atom interferometers or cold-atom ensembles, which profit from mature control techniques and long coherence times. A growing number of variants tweak the details — using rotational superpositions, superconducting levitation, or magnetic microchip traps — to reduce backgrounds and make the protocol more robust.

What the lab must overcome

The experimental challenges are severe but concrete. First, the masses must be isolated so that electromagnetic forces (Casimir–Polder interactions, stray charges, magnetic dipoles) do not mimic or overwhelm the tiny gravitational coupling. That requires ultra-clean surfaces, conductive shielding, and sometimes superconducting components. Second, creating and preserving large spatial superpositions for massive objects demands cryogenic vacuum, active vibration suppression, and exquisite control of magnetic and electric field noise. Third, decoherence from background gas collisions, blackbody radiation, and fluctuating fields must be suppressed long enough for the tiny gravity-induced phase to build up and be read out.

Theorists and experimentalists are actively addressing these problems. Recent technical proposals recommend micro-fabricated diamagnetic chip traps and integrated superconducting shielding to combine strong magnetic gradients for coherent control with the screening needed to eliminate non-gravitational coupling. Other studies quantify how sensitive these setups are to magnetic-noise-induced decoherence and which engineering tolerances are required to reach the parameter regimes where a gravitationally mediated entangling phase would be visible. These papers show that while the demands are exacting, they are not obviously unreachable with focused effort and investment.

Roadmap and near-term prospects

No laboratory has yet reported an unambiguous gravity-mediated entanglement measurement. Instead, the field is in an intensive development phase: teams worldwide are demonstrating ground-state cooling of levitated objects, improving isolation, and testing screening geometries. Several recent theoretical works have also relaxed previously pessimistic requirements by identifying smarter geometries, longer integration strategies, and improved electromagnetic screening techniques that push the required masses and superposition sizes into a more accessible window. Progress in quantum sensing — cavity optomechanics, atom interferometry, and high-fidelity spin readout — is accelerating the practical timeline.

Why this matters beyond fundamental physics

Setting aside philosophical appeal, the push to build these delicate experiments drives technology that has broader impact: ultra-stable traps, force sensors a million times more sensitive than existing devices, and techniques for isolating mesoscopic quantum systems. Those advances feed quantum metrology, navigation, and tests of other tiny forces or hypothetical particles. In short, the work to test gravity at the quantum level stretches both our conceptual picture and the toolkit of precision experimental physics.

Outlook

The idea that a lab bench in a university basement could probe the quantum nature of spacetime was once faint science fiction. Today it sits at the crossroads of quantum information, precision sensing, and gravitational theory: a field of clear ideas, real engineering roadmaps, and active global effort. Whether the coming decade yields the decisive entangling run or a cascade of improved null bounds, the experiments themselves are guaranteed to teach us about the limits of control and coherence in mesoscopic quantum systems — and, perhaps, about the deepest fabric of reality.