The biggest black hole smashup ever detected challenges how we think black holes form

When the quiet of spacetime broke

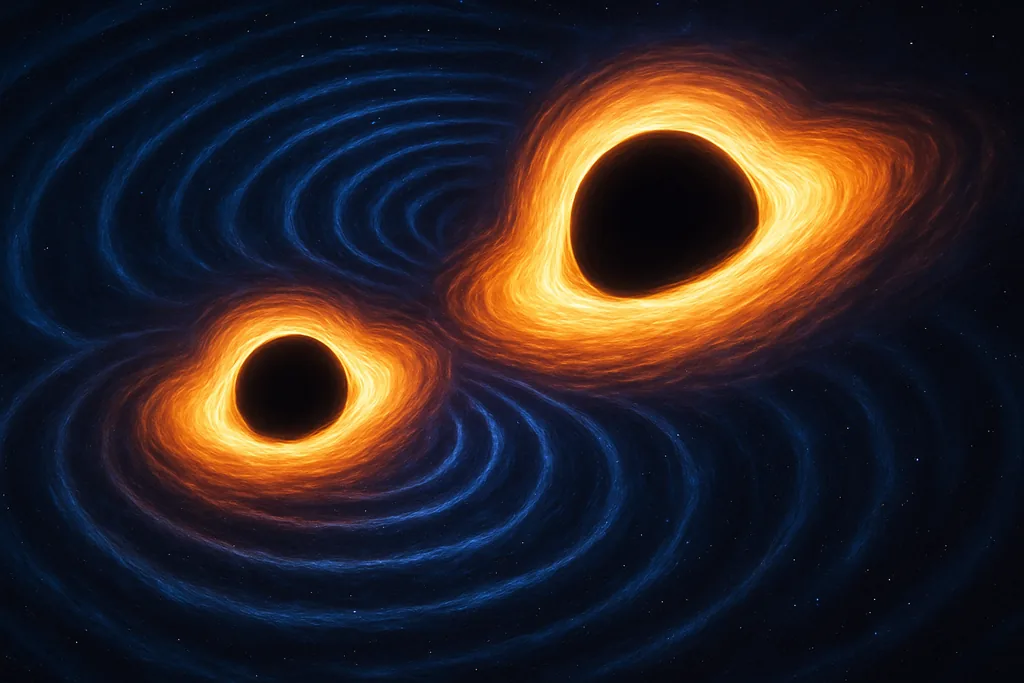

On Nov. 23, 2023, Earth's most sensitive gravitational‑wave instruments registered a brief but loud ripple in spacetime. The signal was so unusual that researchers continued to study it for months — and when the results were unveiled in mid‑July 2025 they upended expectations about how the heaviest stellar black holes are born.

What was detected

Why this is a problem for standard theory

For decades stellar evolution models have predicted a gap in the black‑hole mass spectrum. Very massive stars that would nominally produce black holes between roughly 60 and 130 solar masses are expected instead to undergo a pair‑instability process that either ejects much of the star's mass or blows the star apart entirely, leaving no compact remnant. That theoretical range has been called the “pair‑instability mass gap.”

How could such massive, fast‑spinning black holes form?

- Hierarchical mergers: In dense environments like globular clusters or the crowded centres of young star clusters, black holes can merge repeatedly. Each merger produces a heavier, often rapidly spinning remnant that can later find another partner. Repeating that process over generations can build objects in and above the mass gap.

- Feeding inside an active galactic nucleus (AGN): Massive black holes orbiting inside the dense, gaseous disk around a supermassive black hole may accrete gas and migrate, increasing in mass before merging. That environment can also align or misalign spins in complex ways, producing the high spins seen in GW231123.

- Exotic channels or stellar physics revisions: Some models propose modifications to how pair instability operates — perhaps due to different metallicity, rotation or mixing in the progenitor stars — which could allow direct formation of heavier remnants than previously thought.

Each scenario has strengths and weaknesses. The very high spins measured for GW231123 favour a hierarchical origin in which earlier mergers pumped up angular momentum. But hierarchical channels also tend to randomise spin directions across generations, which can leave signatures in the gravitational waveform that are harder to confirm given the brevity of this signal.

Why the data are tricky to interpret

Because the two merging black holes were so massive, the detectors captured only the final instants of their inspiral and merger — roughly a tenth of a second. That means fewer gravitational‑wave cycles and less information to pin down parameters such as mass ratio, orientation and spin tilt angles. Different waveform models used to infer the system's properties do not agree perfectly, introducing systematic uncertainties in the mass and spin estimates.

Those modelling differences matter: if one waveform family prefers slightly different masses or spins than another, the astrophysical interpretation — whether the components truly sit in the mass gap or instead bracket it — can change. The collaboration has therefore been conservative about claimed precision and is pursuing follow‑up work on improved waveforms and independent analyses.

Where this fits in the bigger picture

GW231123 follows earlier gravitational‑wave detections that hinted at unexpected heavyweight black holes. The first clear intermediate‑mass black hole formed from a binary, GW190521 in 2019–2020, already challenged models. Reanalyses of archival LIGO data have also surfaced candidate events that would produce intermediate‑mass remnants, suggesting we may be seeing a previously hidden population.

Evidence for multiple heavy mergers has broad consequences. It affects our understanding of how the first generations of stars lived and died, the dynamics inside dense star clusters, and the role of gaseous galactic environments. It also provides an empirical route to build intermediate‑mass black holes — a long‑sought bridge between stellar‑mass and supermassive black holes.

What happens next

Researchers will refine parameter estimates using more sophisticated waveform models, targeted numerical relativity simulations and independent parameter‑estimation codes. Machine‑learning techniques and reanalyses of archived data will also keep turning up candidate heavyweight mergers, which will help build statistical confidence in the population.

A strain and a new opportunity

GW231123 is not just another entry in a growing catalogue of gravitational‑wave discoveries. It is a challenge: a data point that presses against a theoretical boundary and forces astrophysicists to widen or replace part of the standard story. Whether the answer lies in repeated collisions inside crowded clusters, hungry black holes swallowing gas in galactic nuclei, or a revision of stellar death physics, the discovery opens a fresh window on how nature builds the heaviest compact objects.

For now, the signal is a striking reminder of the scientific value of listening to the universe in gravitational waves — and that some of the cosmos’s most interesting secrets arrive as a brief, powerful whisper.

James Lawson is an investigative science and technology reporter for Dark Matter. He holds an MSc in Science Communication and a BSc in Physics from University College London.