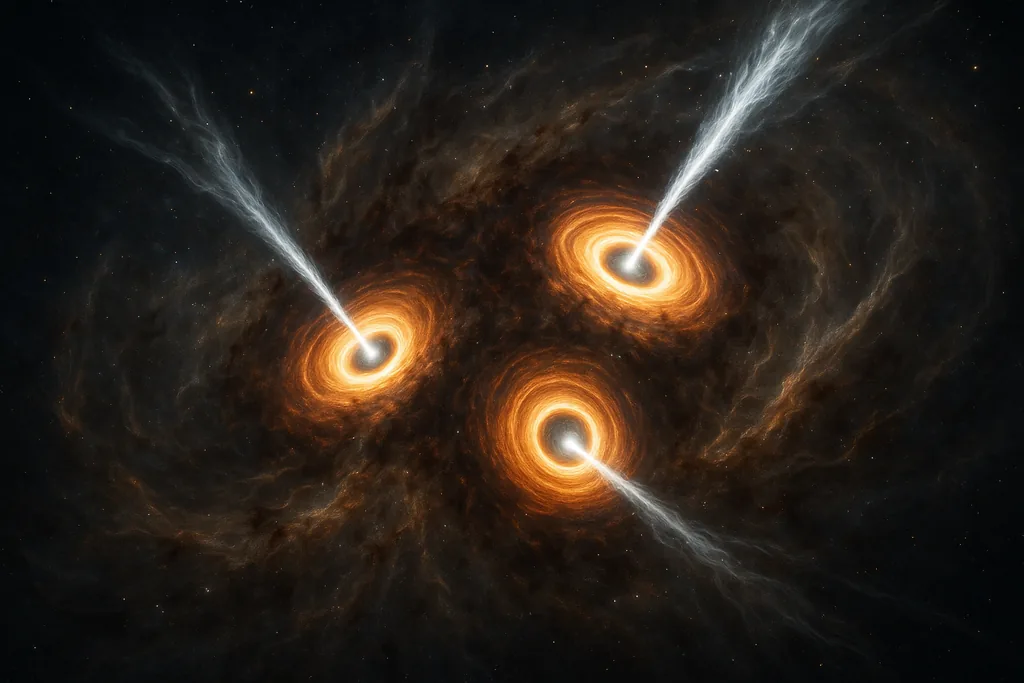

Three giants in a confined space

In the chaotic heart of the nearby galaxy NGC 6240, astronomers have resolved not two but three supermassive black holes crowded into a volume under a kiloparsec across — a configuration that promises to change how researchers think the very biggest black holes form and merge. High spatial‑resolution spectroscopy with the MUSE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope revealed that the southern nucleus, long thought to be a single object, is in fact two distinct nuclei separated by roughly 198 parsecs; the three heavyweights all weigh at least on the order of 9×107 solar masses and sit inside a region less than about 3,000 light‑years across.

How the triple was found

Why triple systems matter for galaxy evolution

Simulations and measured timescales

Follow‑up dynamical modelling, using N‑body simulations tuned to the observed parameters of the NGC 6240 core, gives rough timelines for how the triple will evolve. In those models the two closely spaced southern objects (labelled S1 and S2 in the literature) can form a bound binary within a few million years, and the larger triple system can settle into a hierarchical configuration on a longer timescale of order tens of millions of years. Those studies also show that three‑body effects such as Kozai–Lidov oscillations and chaotic encounters can pump orbital eccentricities and shrink separations, hastening eventual gravitational‑wave–driven inspiral. In other words, triple systems can act as accelerants for heavy‑weight mergers.

Context: triple black holes are rare but not unprecedented

NGC 6240 is not the first reported triple nucleus, but it is among the clearest and closest examples where high‑quality spectra separate the components. Earlier multiwavelength campaigns discovered other candidate triples — for example SDSS J0849+1114 was identified through infrared, X‑ray and optical follow‑up as a system hosting three actively accreting massive black holes — and recent radio imaging has revealed a rare triple radio active galactic nucleus in a different merging group designated J1218/1219+1035. Those discoveries, across different wavebands and distances, point to a small but growing sample of systems where multiple massive black holes coexist and will eventually interact.

Signals for gravitational‑wave astronomy

Black hole mergers produce gravitational waves, but the frequencies depend strongly on mass. Mergers of supermassive black holes radiate at millihertz or lower frequencies — below the band of ground‑based detectors like LIGO and Virgo — and are targets for future observatories such as the space‑based LISA mission and for pulsar timing arrays that are sensitive to nanohertz waves. Because triple interactions can speed up coalescence and produce high eccentricities, they change the expected timing, amplitude and spectral content of the gravitational‑wave signals. In practice, a nearby triple like NGC 6240 will not merge in human timescales, but studies of its dynamics help refine event rates and waveforms for next‑generation detectors.

Observational challenges and caveats

Interpreting crowded galactic nuclei is difficult. Projection effects, obscuring dust, starburst activity and tightly intertwined gas flows can mimic or mask kinematic signatures of multiple black holes. The certainty in NGC 6240 comes from combining instruments that see different physical processes — stellar motions in the optical, hot gas and accretion in X‑rays, and compact radio cores — and from the improved spatial resolution that MUSE’s narrow‑field adaptive optics offers. Even so, measuring precise masses and orbital parameters requires continued monitoring and complementary observations (for example very‑long‑baseline radio interferometry and deep X‑ray imaging). The current mass estimates are model dependent and should be refined as more data arrive.

Why the discovery matters now

Finding three massive black holes so close together in a relatively nearby galaxy gives astronomers a concrete example to test theories that previously relied largely on simulations. It supports a picture in which ultramassive black holes — the giants that tip the scale at billions of solar masses — can be built not only by feeding or repeated pairwise mergers over long times, but also by more dramatic, multi‑galaxy interactions where several nuclei collapse into one central engine. That has implications for galaxy morphology, star formation histories, and the growth of nuclear activity across cosmic time.

Next steps for telescopes and theory

Follow‑up work will aim to pin down orbits and masses more tightly, search for signatures of interaction‑driven accretion, and extend searches for other triple systems. Higher‑resolution radio interferometry can test for compact AGN cores and jets, while deeper X‑ray exposures can reveal accretion that optical light misses. On the theoretical side, incorporating realistic stellar and gas backgrounds into three‑body general‑relativistic simulations will improve predictions of how quickly such systems coalesce and what electromagnetic and gravitational‑wave signatures they produce. Together those efforts will turn rare snapshots like NGC 6240 into statistically useful constraints on black‑hole demographics and merger physics.

What astronomers will watch for

- Refined mass and position measurements using VLBI radio and further adaptive‑optics optical/IR spectroscopy.

- Cross‑matching similar morphological and spectral signatures in large surveys to build a larger triple sample.

NGC 6240’s triple heart is a vivid reminder that galaxy centers are dynamical places where gravity, gas and time collaborate to build the universe’s most extreme objects. As telescopes and simulations improve, systems like this will move from curiosities to cornerstones in our understanding of how the largest black holes attain their masses and how their mergers light up the low‑frequency gravitational‑wave sky.

Sources

- Astronomy & Astrophysics (Kollatschny et al., "NGC 6240: A triple nucleus system in the advanced or final state of merging").

- Astronomy & Astrophysics (dynamical modelling paper on NGC 6240 triple SMBH evolution).

- Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) press materials and institutional research summaries.

- NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Chandra / multiwavelength follow‑up literature on triple active nuclei (SDSS J0849+1114).

- Astrophysical Journal Letters (radio discovery of a triple radio AGN in J1218/1219+1035).