Time Reflection Confirmed; Propulsion Claims Persist

When a lab made waves move backwards

On 11 October 2025, a team in New York said they had done something that reads like a physics parable: they produced an electromagnetic signal that reflected not in space but in time. Instruments recorded a time‑inverted copy of an incoming wave after the researchers flipped a material’s electrical properties almost instantaneously across the device. The effect is not a movie trick—measurements show the reversed waveform and a corresponding change in frequency—but it arrives wrapped in the caveats scientists always demand for startling results: independent replication and theoretical integration remain necessary.

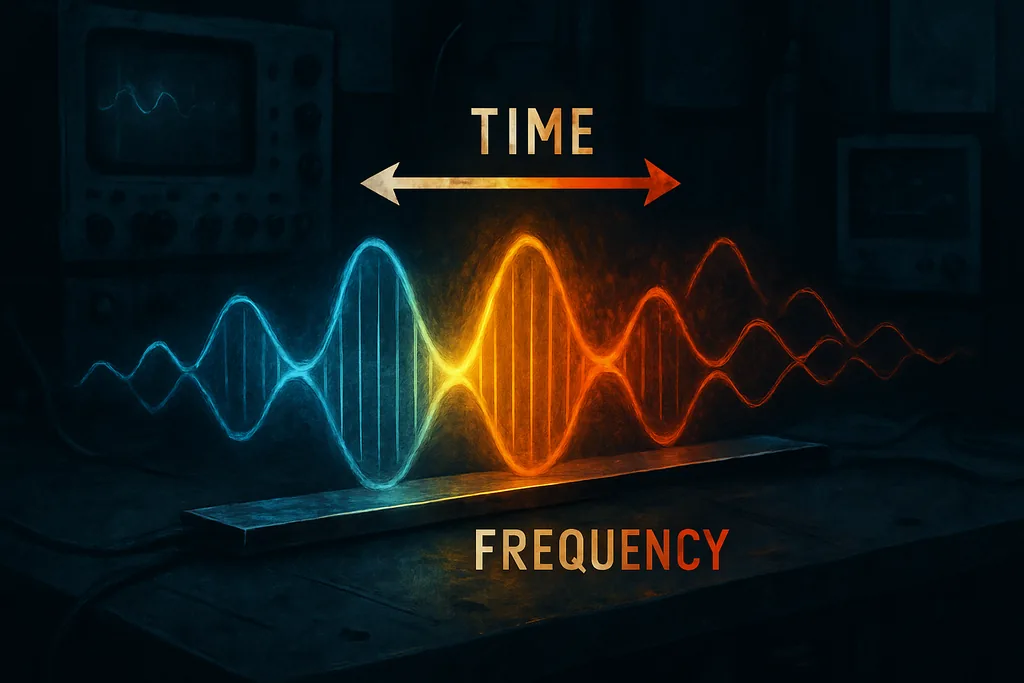

What 'time reflection' actually means

Every physics student learns about spatial reflection: a light ray bounces off a mirror, an echo returns from a canyon. Time reflection is the temporal analogue. Instead of an incoming pulse bouncing back along the same spatial path, part of the pulse is converted into a wave that propagates backward along its own time axis. In practical terms, the lab detectors saw a reversed copy of the original electromagnetic waveform—like a recording played in reverse—together with a shift in frequency that they associate with the abrupt change they imposed on the material.

The trick, in the experiment, is the timing and uniformity of the change. The research team built a metallic strip embedded with ultra‑fast electronic switches and capacitances able to change the strip’s impedance extremely rapidly. By synchronising those switches across the device the team achieved a near‑instantaneous, uniform change in the medium through which the wave travelled. That sudden temporal boundary is what theory predicts can produce time‑reversed components.

Why physicists are excited—and cautious

If the observation holds up under scrutiny, it is an important experimental confirmation of a theoretical effect that has been discussed for decades. Time‑reflected waves carry implications beyond the novelty: engineers foresee potential applications in communications, radar and imaging. In a world where signals can be manipulated with exquisite control over phase and time, new protocols for secure transmission or forms of signal processing could follow.

On the other end of the extraordinary: propellant‑less propulsion

For advocates, the implications are intoxicating: launch systems that don’t need heavy fuel, missions that could accelerate for long periods without carrying vast reaction mass, and dramatic reductions in the cost and complexity of space travel. For many physicists, the claim triggers an alarm bell because it appears to clash with conservation laws that underpin classical mechanics and electromagnetism: conservation of momentum and energy.

History and hard lessons

The idea of reactionless drives is not new. Past claims—most notably devices proposed in the early 2000s—generated intense experimental and public scrutiny. Some preliminary positive results were later explained by experimental error, thermal effects, or measurement bias. That history has made the community rightly wary and raised the bar for evidence: careful error analysis, independent replication, and open data are essential before a claim can supplant fundamental principles.

The propulsion team says its concept is rooted in electrostatics and asymmetry rather than exotic external inputs, and it emphasises the need for third‑party tests. Critics point out that until independent laboratories reproduce the effect and rule out mundane causes, extraordinary claims should be treated as provisional. The tension is familiar in science: big ideas excite fast, but only reproducible evidence converts skepticism into revision of theory.

Two challenges, two evidentiary stages

These two stories are related only in their capacity to unsettle received wisdom. The time‑reflection report comes with an experimental protocol and instrument traces; if replicated, it slots into existing electromagnetic theory as a nontrivial boundary condition phenomenon and will prompt work on how to reconcile it with thermodynamics and information flow. The propulsion claim, by contrast, currently lives at an earlier stage: a company announcement and laboratory statements rather than a body of independent confirmations or peer‑reviewed analyses.

That difference matters. A single well‑controlled experimental observation can be integrated into the web of physics more readily than a claim that, if true, demands a wholesale rewrite. In practical terms, the community will demand measurement transparency for the propulsion system, open replication attempts and tests designed specifically to rule out instrumental artefacts, buoyancy, ionic winds, or electromagnetic interactions with the environment.

How physicists will test and respond

For time reflection, the near‑term agenda is straightforward: independent laboratories will try to reproduce the effect with different materials and detection schemes. Theoretical physicists will work to place the observation within rigorous formalisms—mapping the laboratory temporal boundary onto scattering theory, thermodynamic constraints and quantum field descriptions. If the effect is robust, engineering groups will begin exploring applications while fundamental theorists examine implications for causality and entropy.

For the propulsion claim, the path is longer. The community will look for careful thrust measurements that include null tests, calibration against known effects (thermal expansion, electromagnetic reaction with nearby conductors, ionic wind), and open reporting of apparatus geometry and data. Only after repeated, independent demonstrations under controlled conditions will the wider field entertain serious revisions to conservation principles.

Why this matters beyond headlines

Both stories illuminate how science advances: a mix of surprising measurement, sceptical replication and conceptual reconciliation. The public appetite for dramatic headlines—mirrors for time or engines that break the rules—collides with the slower, careful work that turns an observation into trusted knowledge. The difference between a replicated laboratory effect and an unverified technological claim is not a matter of degree but of scientific method.

If time reflection becomes a standard experimental tool, it could seed new technologies and sharpen our theoretical tools for handling non‑stationary media. If a propellant‑less drive were validated, the consequences would be profound and immediate—but the cautionary examples of past decades advise that such a validation must be incontrovertible.

What to watch next

Expect published data sets, preprints and replication attempts to appear in the weeks and months ahead. Conferences and specialist workshops will host the first technical debates: signals and boundary conditions on one stage, precise thrust tests and null experiments on the other. Until independent teams reproduce either claim under rigorous conditions, the scientific response will be a mixture of guarded interest, scepticism and, for the lucky few, the start of new research programs.

These are exhilarating moments: the frontier feels close enough to touch, yet the discipline of verification remains the gatekeeper. That tension—between the shock of possibility and the hard work of proof—is how physics separates hope from knowledge.