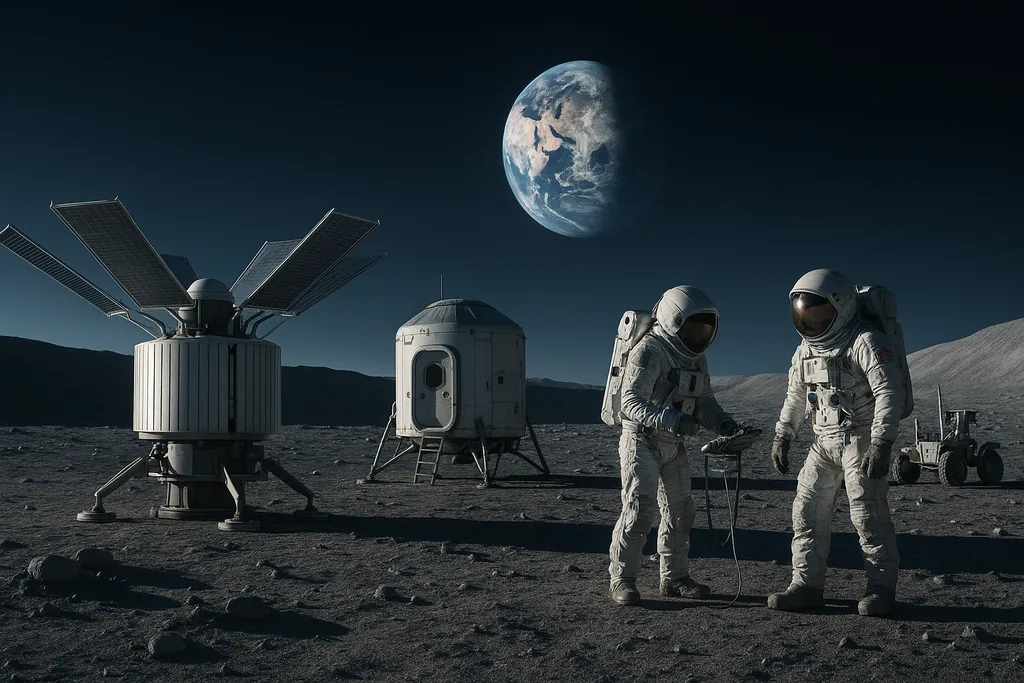

Washington doubles down on Artemis and lunar power

This week, on 19 December 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order that pushes the United States to return astronauts to the lunar surface and to begin building a permanent presence there — with nuclear reactors explicitly named as the backbone of that outpost. The directive reaffirms an aggressive timetable: crewed return missions aimed for 2028, an established lunar outpost by about 2030 and the deployment of nuclear power systems "on the Moon and in orbit." It also folds responsibilities for national space policy into the Office of Science and Technology Policy and directs the development of new space-domain defence capabilities under a programme the order calls Golden Dome.

A White House push for lunar power

The White House move follows internal NASA direction earlier this year that set a 2030 target to field a fission-based surface power system capable of continuous electricity generation for a crewed base. Officials and outside experts who have briefed agencies describe the required capacity as a relatively modest 100 kilowatts electric for an initial system — far below terrestrial gigawatt-class plants but enough, in theory, to run life-support systems, communications, processing and habitat systems through the Moon's two‑week nights.

Administration documents and agency directives released during 2025 link that technical push to a geopolitical objective: preventing rival actors from establishing de facto exclusion zones around lunar infrastructure. Acting NASA leadership has warned that if competitors reach and secure key locations first, they could create operational "safety" or "keep-out" zones that would complicate later American activity. That concern helped crystallise the policy decision to prioritise urgency alongside a commercialisation agenda that seeks to shift more of the architecture to private suppliers.

How a lunar reactor would work

Designs for a lunar fission reactor borrow basic principles from terrestrial reactors but must adapt to the Moon's vacuum, thermal environment and logistic constraints. In short: a controlled nuclear reaction produces heat, that heat is converted to electricity through a power conversion system, and excess heat is rejected by large radiators that radiate directly to space. Without atmosphere or water to assist cooling, radiator area and high-temperature operation become central engineering challenges.

Developers propose compact reactors optimized for launch and robotic emplacement, fuelled with highly engineered uranium cores that would be launched in a non‑critical configuration and only brought to power after emplacement. That approach reduces—but does not eliminate—radiological risk during ascent and delivery. The reactor must also be hardened against micrometeoroid impacts and lunar seismic activity, and mission planners must solve long-term end‑of‑life and disposal questions to avoid any hazardous re‑entry scenario if hardware is returned to Earth.

Budget, workforce and schedule tensions

The new push comes amid stark fiscal and personnel pressure for NASA. In 2025 the administration proposed steep reductions in the agency's baseline budget even as a recent congressional bill redirected nearly $10 billion toward NASA activities through 2032. The agency has also seen significant voluntary departures from its workforce, compounding delivery risk for ambitious programmes.

Independent and academic analysts who have modelled lunar fission systems put the development bill at hundreds of millions to a few billion dollars over several years for an initial demonstrator — a large but not unmanageable slice of the wider Artemis programme budget. Still, operating a credible 2030 delivery schedule for a fully integrated power plant on the Moon is widely judged optimistic. Engineers point to long development cycles for new nuclear hardware, the need for interagency reviews and licences, and the logistical burden of delivering multiple launches and surface infrastructure before a reactor can be safely brought to power.

Safety, liability and regulatory gaps

Several senior technical voices argue that authorisation and oversight must involve multiple U.S. agencies — especially the Department of Energy — and that international consultation will be essential if the United States wants to preserve norms against weaponisation while enabling scientific and commercial activity. Analysts also warn against speeding nuclear authorisations without robust safeguards and transparent risk communication to allies and the public.

The geopolitical backdrop

The executive order lands against a fast‑moving international push for lunar infrastructure. China and Russia have announced plans for an automated, nuclear‑powered International Lunar Research Station in the mid‑2030s. European, Japanese and other partner nations are also advancing technologies that could be plugged into a cislunar economy. That competitive dynamic is a major driver of the White House urgency: policymakers now frame lunar power capability not solely as science and exploration but as an element of strategic advantage in cislunar space.

That shift raises questions about the traditional science-led model of space exploration. Some planetary scientists caution that competition framed as first‑to‑site contests risks narrowing cooperative science and could encourage defensive or exclusionary practices around lunar operations. Others argue competition fuels investment and technical innovation. Either way, the policy calculus now explicitly joins civilian exploration objectives, industrial strategy and national security planning.

Commercialisation, industrial strategy and next steps

The executive order pairs the reactor objective with a broader aim to attract private capital into American space markets and to move some returns-to-the-moon architecture onto commercial providers. That approach reflects both a belief that private suppliers can lower launch and integration costs and a strategic preference to spread development risk outside traditional government programmes.

For the immediate future the critical path will test three things: whether NASA and the Department of Energy can agree and fund a technically viable reactor demonstrator; whether commercial providers can deliver launch and robotic emplacement services at scale; and whether Congress will sustain the appropriations needed to meet the compressed timetable. International coordination or at least transparency on safety and deconfliction will also matter if the United States wants to avoid turning the moon into a patchwork of contested zones rather than a platform for shared science and commerce.

The policy decision taken this week makes nuclear fission an explicit plank of U.S. lunar strategy. Turning that policy into a safe, affordable and internationally acceptable capability will require the technical mastery of new hardware, patient interagency work, and clear diplomatic choreography — all while rivals race toward the same objective.

Sources

- NASA (Artemis programme and Fission Surface Power project)

- U.S. Department of Energy (nuclear technology and safety assessments)

- Office of Science and Technology Policy (White House space policy offices)

- University of Illinois at Urbana‑Champaign (nuclear engineering expertise)

- University of Surrey (space applications and lunar power research)

- Lancaster University (planetary science and exploration analysis)

- German Marshall Fund of the United States (policy analysis on cislunar competition)

- China National Space Administration / China Lunar Exploration Program (International Lunar Research Station planning)