Viagra-like Drug Restores Hearing in Genetic Models

A new study links rare CPD gene mutations to congenital hearing loss and shows that restoring arginine–nitric oxide signaling — with supplements or sildenafil — rescues auditory cells in mice and flies, opening a cautious path toward repurposing an existing drug.

Researchers find a surprising molecular rescue for certain deafness

In a paper published this year in a leading clinical journal, an international team led from the University of Chicago has identified a genetic cause of congenital sensorineural hearing loss and — importantly — demonstrated ways to reverse the damage in laboratory models. The culprit is a previously underappreciated role for the CPD gene, and the remedy they tested includes L-arginine supplements and sildenafil, the active ingredient in drugs best known for treating erectile dysfunction.

What the team discovered

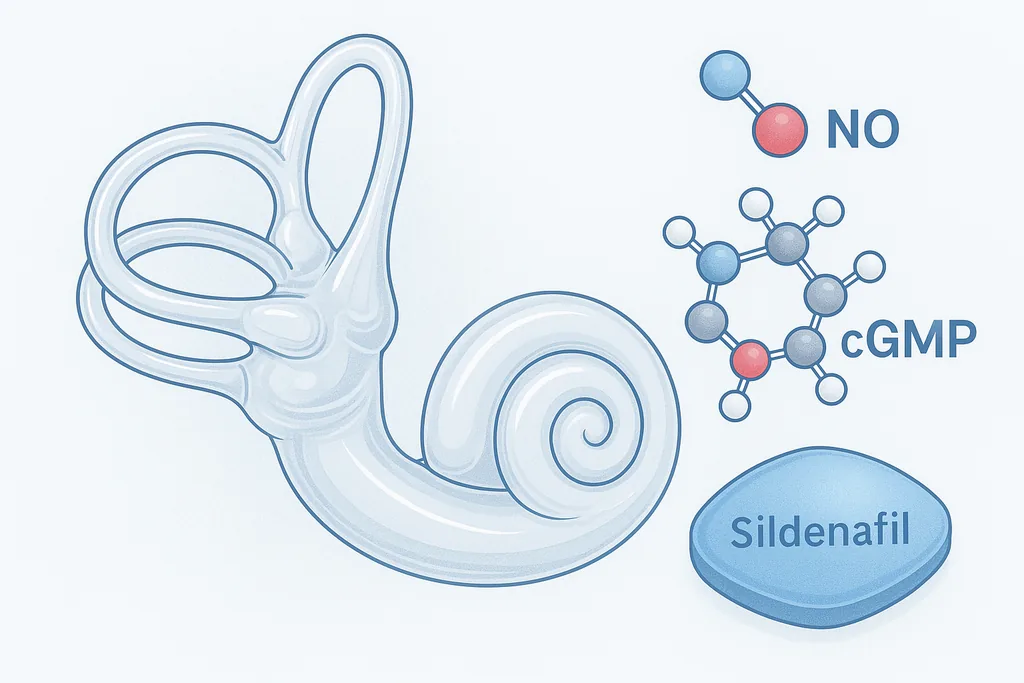

At the cellular level, CPD activity turns out to be important for maintaining arginine — the amino-acid substrate needed to make nitric oxide (NO). In the delicate sensory hair cells of the inner ear, loss of CPD reduces arginine availability and downstream NO signaling. That shortage increases cellular stress and triggers pathways that culminate in hair‑cell death, the irreversible damage that underlies many forms of sensorineural hearing loss.

How sildenafil fits into the biology

Nitric oxide acts as a signalling molecule that, among other effects, stimulates production of cyclic GMP (cGMP). Enzymes known as phosphodiesterases (PDEs) break down cGMP; sildenafil inhibits one of those enzymes (PDE5), effectively boosting cGMP signalling. In the study, the team reasoned that enhancing cGMP could compensate for reduced NO production caused by CPD deficiency.

In cultured patient-derived cells, in organotypic mouse cochlear preparations, and in fruit‑fly models of CPD loss, supplementing arginine or pharmacologically enhancing the cGMP pathway with sildenafil improved cell survival and partially restored auditory function. In flies, behavioural measures related to hearing and balance improved. In cochlear cultures and cell systems, markers of oxidative and endoplasmic-reticulum stress decreased when arginine or sildenafil was applied.

Why this is noteworthy

- A defined molecular mechanism: the work links a single biochemical pathway — arginine → nitric oxide → cGMP — to hair‑cell health, offering a clear target for intervention.

- Therapeutic potential for a genetic form of deafness: unlike most sensorineural hearing loss, where no drug treatments reverse the damage, this form appears amenable to biochemical rescue in models.

- Repurposing a known drug: because sildenafil is already FDA approved for other uses, the route from lab to clinical testing could be faster than for a wholly new compound — though that speed comes with caveats described below.

Important caveats and unanswered questions

Despite the promise, several reasons counsel caution before anyone considers sildenafil a hearing cure.

- Rare, specific mutations: the experiments target CPD loss-of-function variants. Most hearing loss in the population is age-related or noise-induced and has complex causes; it is not yet known how commonly CPD variants contribute to human deafness beyond the families described.

- Model systems are not humans: the team used mice, cultured human cells, and fruit flies. These are powerful tools for establishing mechanism and proof‑of‑concept, but they cannot fully predict safety, dosage, distribution into the human inner ear, or long‑term effects.

- Systemic vs local dosing: sildenafil circulates throughout the body. Whether effective doses for the inner ear would be safe systemically — or whether local delivery to the cochlea would be required — remains unresolved. The inner ear is a small, tightly sealed organ where drug access and concentration differ greatly from other tissues.

- Mixed prior evidence: animal research over the past decade has produced mixed signals about whether PDE5 inhibitors protect or harm hearing under different conditions. Some studies report protective effects in noise or blast models; others show no change. In humans, there are rare case reports suggesting sudden hearing changes with PDE5 inhibitors, but population‑level evidence is inconsistent. Thorough clinical evaluation will be necessary.

What would come next?

The typical pathway from a study like this toward clinical use involves several steps. Researchers must first confirm how common CPD variants are in broader hearing-loss cohorts and determine whether partial CPD function or single‑copy variants raise susceptibility to later‑life hearing decline. Next are preclinical studies to optimise dosing, delivery method, and timing, followed by carefully designed early human trials focusing on safety and biological activity in the ear rather than immediate hearing restoration.

If early human studies find a safe dosing window and evidence that the drug reaches cochlear targets, then small efficacy trials could test whether arginine supplementation, systemic sildenafil, or targeted cochlear delivery improves hearing or slows progression in people with confirmed CPD-related deficits. Because sildenafil is already approved for other indications, regulators will still demand specific safety and efficacy data for any new use.

Big-picture implications

Beyond the specific CPD story, this work illustrates two broader trends in modern biomedical research. First, genetic detective work — linking rare familial cases to molecular pathways — can reveal druggable vulnerabilities that are missed in population-level studies. Second, repurposing existing drugs based on molecular insight is an efficient translational strategy when the biology is clear and the safety profile of the drug is well characterised.

I'm James Lawson reporting for Dark Matter. This research is a reminder that sometimes established drugs can find surprising new uses when examined through the lens of modern genetics and molecular neuroscience.