Lede: a syringe, DNA and a disappearing weapon

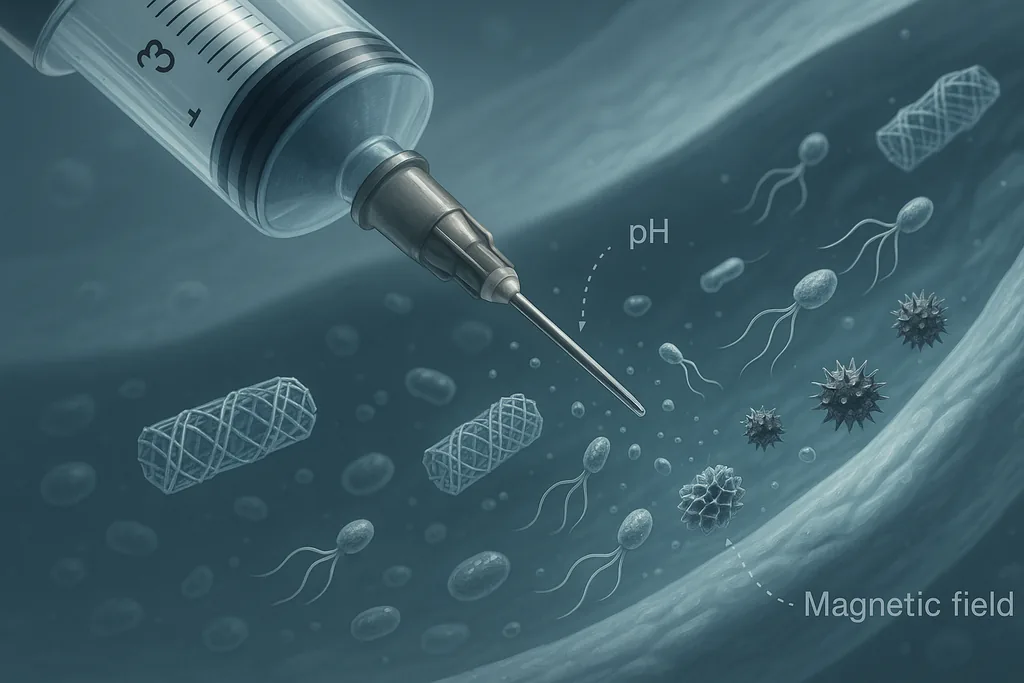

In a lab at Karolinska Institutet, researchers folded strands of DNA into a hollow tube no wider than a virus, tucked a peptide 'weapon' inside its cavity, and injected the assembly into mice with breast tumours. The peptide remained hidden while the nanostructure circulated in blood but unfolded and exposed its lethal pattern in the acidic microenvironment that surrounds tumours — producing a roughly 70% reduction in tumour growth in the animals compared with an inactive control. The work, described in a Nature Nanotechnology paper and presented in a university press release this year, is one of several striking demonstrations that architectures often labelled "nanorobots" can carry out targeted actions inside living organisms.

Different flavours of injectable nanomachines

Other teams pursue biohybrid microrobots that swim. Researchers at the University of California San Diego have attached drug‑loaded nanoparticles to motile algae to create tiny swimmers that can carry cargo deep into lung tissue and home to metastatic nodules; in mice the swimmers slowed tumour spread and improved survival compared with controls. These systems are larger (micrometre rather than nanometre scale) and exploit natural propulsion rather than pure molecular folding.

Where the name 'robot' helps — and where it misleads

Calling these devices "robots" is rhetorically powerful but can obscure technical reality. Unlike macroscopic robots, most injectable designs do not carry onboard processors, motors or batteries. Their intelligence usually comes from chemistry: sequences of DNA or protein that change conformation in response to a molecular cue, or from physical steering by magnets. Those behaviours are programmable and repeatable, but they are not autonomous cognition; they are more like conditional drug depots than miniature androids. Still, the term captures that these constructs can sense, change shape and actuate a therapeutic effect in situ — a set of capabilities that were science fiction not long ago.

Why the animal results are promising but not decisive

Mouse studies are essential first steps, but they leave several crucial questions unanswered. Tumour models in mice often have simpler vasculature and immune context than human cancers; biodistribution, off‑target accumulation and systemic immune responses can differ dramatically when moving to larger animals and humans. For DNA‑based devices, degradation by nucleases in blood, unintended immune recognition and safe, consistent manufacturing at scale are practical obstacles. For biohybrids and magnetic systems, long‑term biocompatibility, the risk of emboli, and the ability to deliver enough active payload to a clinically meaningful fraction of tumour tissue are unresolved. Researchers acknowledge these gaps: the teams behind the pH‑activated DNA nanostructure and thrombin nanorobot both called for tests in more advanced disease models and thorough safety studies before human trials.

Manufacturing, stability and regulatory hurdles

Translating nanoscale systems into medicines requires reproducible, high‑yield production and robust quality control. DNA origami currently depends on long scaffold strands and many short staple oligonucleotides; even with advances that conserve scaffold routing and re‑use staple sequences, costs and process control remain nontrivial. Recent engineering work has reduced complexity and improved assembly rules, but manufacturing for clinical use will require new standards for purity, endotoxin control and batch consistency. Regulators will also demand clear modes of action and safety margins: a device that intentionally induces local clotting, for example, must convincingly avoid systemic coagulation. The field is still building the technical and regulatory toolkits to make those demonstrations routine.

Paths to the clinic and the likely timeline

Not all approaches face the same road to clinical use. Simpler payload‑delivery systems that repurpose known biologics may travel faster through regulatory gates than completely novel molecular machines. Devices that use external control (magnetics, ultrasound) can piggyback on established imaging and interventional platforms, potentially shortening clinical development time if safety can be shown. Many researchers predict a staged translation: first, localized or ex vivo uses (such as targeted thrombosis during surgical procedures), then tightly controlled, image‑guided trials in patients with limited options, and finally broader indications if safety and efficacy are confirmed.

Realistic estimates from researchers embedded in the work suggest years, not months, before first‑in‑human trials for most concepts; even optimistic pathways require multi‑year toxicology, scaled manufacturing and regulatory engagement. But the pace of progress — several distinct in‑vivo demonstrations across institutions within a few years — makes the idea of clinically useful injectable nanomachines a plausible mid‑term prospect rather than mere fantasy.

Ethical, clinical and systems implications

Beyond efficacy and safety there are societal questions. Who will pay for complex, potentially expensive nanomedicines? How will equitable access be ensured? What liability frameworks apply if an externally steered device causes unintended damage? Early engagement between technologists, clinicians, regulators and ethicists will be necessary to shape trials and deployment in ways that are scientifically rigorous and socially responsible.

Conclusion: not tomorrow's cure, but a credible toolkit

The recent wave of papers and press releases — from pH‑activated DNA origami that hides cytotoxic peptides to thrombin‑exposing nanodevices and biohybrid swimmers that deliver drugs to lung metastases — shows a convergent trend: engineers and biologists are assembling programmable, injectable constructs that can sense, localize and act inside living tissue. Those capabilities mark a real technological advance. At the same time, the path from mouse to medicine is long, and each design brings its own technical and regulatory puzzles. In the coming years expect careful, staged clinical testing of the safest, simplest designs first, while more ambitious, multifunctional nanorobots continue to mature in preclinical labs.

Sources

- Nature Nanotechnology (paper on pH‑activated DNA nanostructures)

- Karolinska Institutet (press release and research materials)

- Nature Biotechnology (DNA nanorobot delivering thrombin)

- Science Advances / University of California San Diego (microrobots for metastatic lung tumours)

- Advanced Science / University of Illinois Urbana‑Champaign (DNA origami imaging and targeting for pancreatic cancer)